The daring, high-altitude architecture innovating in unforgiving climates

The Milano Cortina Winter Olympic Games inspired us to look up; from the Alps to the Andes, ambitious architecture projects are taking creativity and engineering to dizzying new heights

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

High-altitude architecture and infrastructure never happen by accident. A station or shelter carved into or set atop a mountain is built with great cost and intent, not to mention seemingly insurmountable natural obstacles. Planning and transporting materials to a peak are often as impressive as the architecture itself.

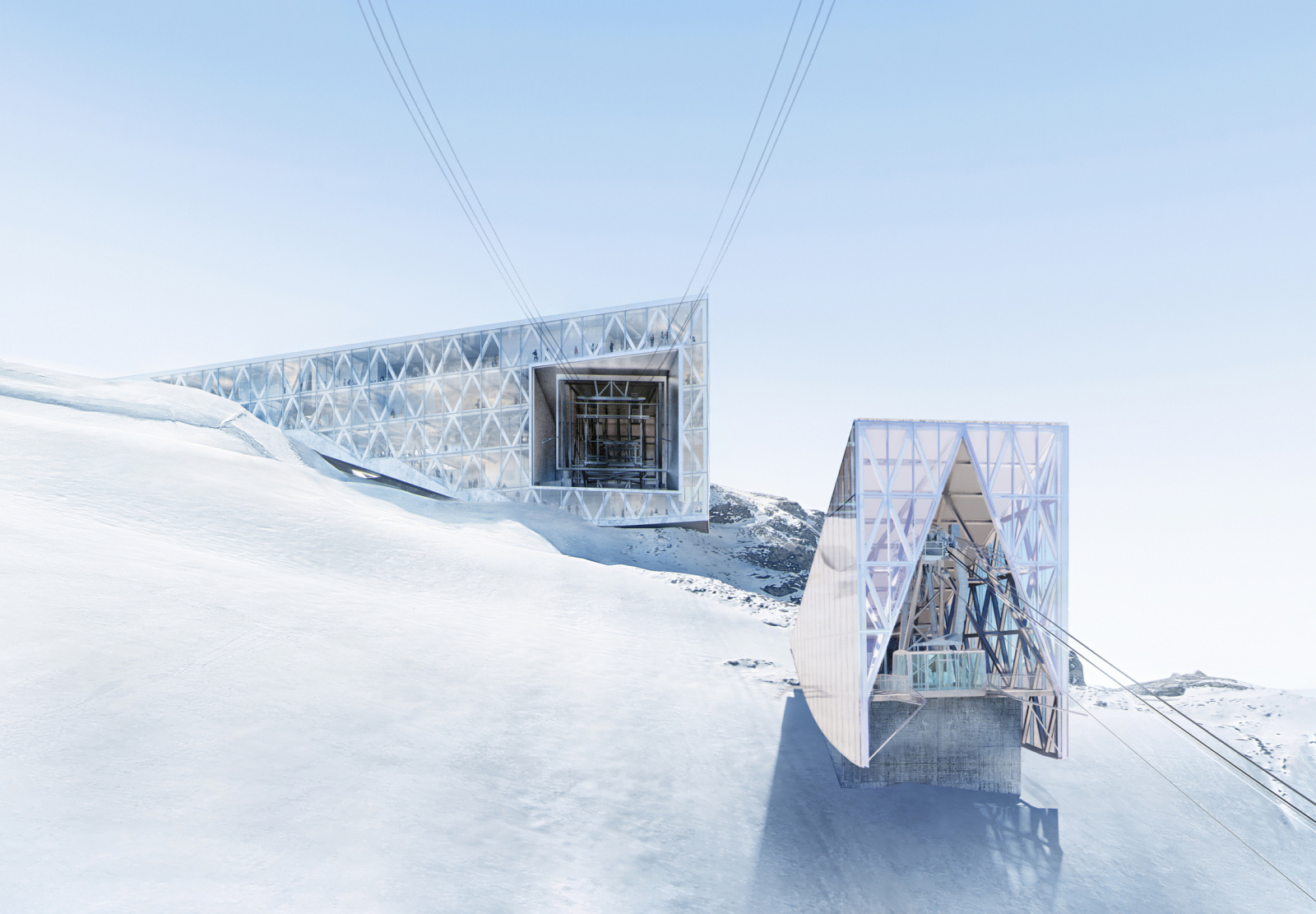

Peter Pichler Architecture's mountain stations in Ponte di legno, Italy

Why build high-altitude architecture?

There have always been reasons to build high. Castles sought protection; monasteries, silence; sanatoriums, fresh, crisp air; temples, proximity to the gods. But today’s high-altitude structures exist resoundingly for downtime leisure. Ski resorts and skyways, bivouacs and cabins, few architects can resist designing a refuge 2,500m in the air. The Instagrammability of such buildings is a panoramic calling card for any practice. Little wonder firms like Herzog & de Meuron, Snøhetta and Zaha Hadid Architects – whose Messner Mountain Museum Corones (2015, 2,275m) is an ode in form and function to the fearless mountaineer that bears its name – have built impressive résumés of mountaintop chalets, outposts and viewing docks that are both technically challenging – wind, power, plumbing, provisions – and impossibly comfortable.

The latest news in high-altitude architecture

2026 will see another slate of remarkable high-altitude achievements, many years and even decades in the making. Featured here are a few of our favourites. What has become apparent is that the architectural bar is as high as the foundations on which these structures are built. Put simply, it is becoming increasingly harder to blow people’s minds. Cliffside-hugging capsules like Skylodge Adventure Suites (Peru, 2013, 3,000m) and OFIS Architekti’s 9.7 sq m Winter Cabin (Slovenia, 2015, 2,700m) and bivouacs like LEAPfactory’s Bivacco Gervasutti (Italy, 2011, 2,835m) and Demogo’s Bivouac Fanton (Italy, 2021, 2,600m) leave precious little room for improvement, both imaginary or real. Then again, Marcel Breuer’s Brutalist Flaine ski resort in Haute-Savoie (France, 1969, 1,600m) still solidly holds its own against all its successors. In Breuer’s view, his resort was less a piece of architecture and more of a total work of art.

7 dizzying examples of high-altitude architecture

As materials continue to improve, as well as derring-do, it appears that the age of architecture in unforgiving climates is only getting started.

Titlis Tower, Switzerland

Titlis Tower complex by Herzog & de Meuron, Switzerland

Back in 2017, Herzog & de Meuron was tasked with creating a comprehensive master plan for Switzerland’s popular Mount Titlis summit, including renewing its mountain station from the late 1960s and repurposing a 50m transmission tower from the 1980s. In May 2026, after eight years, the first stage of the architects’ master plan, the transmission tower, opens to the public. Integrated into the tower’s existing steel structure are two intersecting, fully glazed volumes that house a restaurant, a retail shop and a storage space for snow groomers. The tower is connected by an underground tunnel to the new mountain station, which will open in 2029.

Fred Young Submillimetre Telescope (FYST), Chile

Manufactured by CPI Vertex Antennentechnik in Germany and reassembled at 5,600m on the Cerro Chajnantor in Chile's Atacama Desert, the Fred Young Submillimetre Telescope (FYST) is a remarkable feat of design and engineering. To assemble it required crews kitted out with full oxygen support and safety gear to combat both the cold and high UV (roughly four times that of sea level). Remotely operated, the entire structure demanded special reflecting paints, underground cables, double- and triple-paned windows, sealed at altitude, and robust lightning protection. When the five-storey telescope is inaugurated in April 2026, it will be the second-highest astronomical observatory in the world, second only to its nearby neighbour, the University of Tokyo Atacama Observatory (TAO). From this ideal position in the thin air, the consortium behind FYST anticipates ‘first light’ (first scientific observation) by the end of 2026.

Digitally Fabricated Bivouac

Where one architect prefers maximum visibility, others seek invisibility. This digitally fabricated bivouac by Carlo Ratti Associati falls into the latter category. A collaboration between the architects and the Salone del Mobile, the bivouac debuts as a temporary pavilion at the 2026 Winter Olympics before being airlifted to a not-yet-disclosed location. What differentiates this bivouac from others is its Saville Row fit; CRA uses 3D scans of surrounding rock formations to design a shell structure that perfectly conforms to the shape of its surroundings. Photovoltaic and air condensation systems promote self-sufficiency, while a large glass wall emits a bright glow in times of emergency or low visibility.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Schilthornbahn 20xx Project, Switzerland

Since 2022, Schilthorn Cableway Ltd (Schilthornbahn AG) has been battling both altitude and elements to revamp its cable car system between Stechelberg and Schilthorn, in Switzerland, a trajectory that ends at the legendary revolving Piz Gloria restaurant of Her Majesty's Secret Service fame (it was Blofeld's mountaintop hideout). The three-stage superloop from Stechelberg village to the summit includes high-speed Funifor systems, the world’s steepest aerial cableway with a 159.4 per cent gradient and new mountain stations along the way by Brügger Architekten. The final piece to the Schilthornbahn 20xx puzzle will be unveiled in spring 2026, when Piz Gloria reveals her brand-new copper façade and outward-extending finger docks.

Cabaña Rumi Ñahui, Peru

Completed in late 2025, this temporary shelter by Peruvian R3 Arquitectos was designed to enable comfortable living in the cold, windswept Andean landscape. The entire structure evokes suspended rocks – from the eastward-facing exterior façade to the kitchen sink inside. As with any structure built at such a height, its beauty has a performative side. Its long orientation optimises solar gain, while its faceted façade offers protection from the wind. The westward-facing reflective glass mirror façade reduces the shelter’s visual impact, but also captures the afternoon sun. This off-grid shelter includes both active and passive systems, such as high thermal mass materials and controlled ventilation, as well as a biodigester for waste management.

Europahütte, Austrian/Italian border

The brief for this compact mountain lodge in the Zillertal Alps by Modus Architects was to complement, not overshadow, the original rifugio built in 1899, and to ‘connect’ the two both aesthetically and structurally, in part to enable a panoramic terrace sheltered from the prevailing winds. Constructed almost entirely of prefabricated cross-laminated timber, both inside and out, it is the façade’s overlapping elongated hexagonal shingles that stand out, with integrated cornices and sills and windows of varying sizes, a welcome display of whimsy at 2,740m. While the new structure inevitably overshadows its mother hütte in terms of space and comfort, the upward-sweeping conical roof of the new lodge, created to maximise solar power, perfectly mirrors the old. Literally straddling Austria and Italy, the architects cleverly delineated the precise points where the border cuts through the hut through floor and ceiling jointing.

Valbione Mountain Stations and Hut, Italy

A popular Italian winter sports destination, the Ponte di Legno region is undergoing a large-scale architectural upgrade with the help of Peter Pichler Architecture. Replacing two ski lifts is a new gondola system that includes three new mountain stations, one of which is integrated into a summit hut. The structures are inspired by and pay homage to regional architecture, deploying transparent, lightweight wooden designs to minimise their visual impact on the surrounding landscape. The Italian firm’s approach to the Angelo summit station/hut is particularly telling – rather than build a hulking landmark visible from miles away, it is integrating the station into the mountain. The alpine hut that sits atop the station features a pitched roof that follows the natural slope of the landscape. With no access roads, all materials must be transported via helicopter and a temporary zip-line system built onsite. The entire project is intended to open in 2027.

John Weich is a former travel editor of Wallpaper* magazine and has been contributing to the magazine since 1999. He is the author of several books, including Storytelling on Steroids, The 8:32 to Amsterdam and Ballyhooman, and currently writes, podcasts and creative directs from his homebase in The Netherlands.