Architecture Overview: Chinese Icons

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

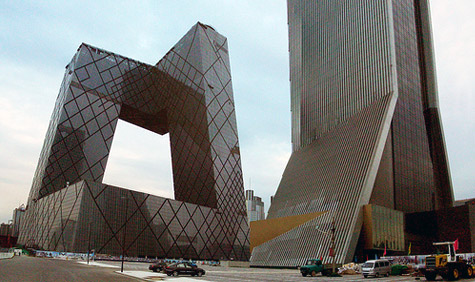

Can you create an architecture culture purely out of icons? A cursory glance over China's burgeoning cityscapes suggests that you can. After the insipid internationalism of the early boom years, when shoddy skyscrapers thrust up through the smog with little concern for aesthetics, new Chinese architecture is a heady blend of imported exoticism and home-grown innovation. Topping the charts is OMA's China Central Television headquarters (pictured above), which completes later this year.

See our gallery of China's architectural attention seekers

To describe the CCTV Tower as unusual-looking is an understatement. The X-storey structure not only turns on unexpected angles, it’s also hollow – but in a clever, stylistic way, not simply an empty gesture. The Office for Metropolitan Architecture is rightfully proud of the structure, and despite the recent catastrophic fire that all but destroyed its adjacent TVCC building, the skyscraper has become one of the most celebrated structures of recent times. But is its iconism an inevitable by-product of the building's media-friendly function, or is CCTV merely the high-water mark for signature architecture, before depressed markets scrub away aesthetic and technological ambition for generations to come?

In recent years, China has been an enthusiastic patron of the Western avant-garde. Suddenly, what was once dismissed as 'paper architecture' was everywhere, or so it seemed from the architectural press, from Kengo Kuma, Morphosis, Zaha Hadid and Herzog & de Meuron, to Steven Holl and Coop Himme(l)blau and more. It's hard to think of a major name that hasn't drawn up a significant Chinese project (although the recent downturn has discouraged any more satellite offices from springing up quite so prolifically). And central to this influx of architectural talent has been the high-profile building, adventures in eccentric formalism that are helping shape numerous home-grown works, albeit with little of the necessary time or talent to capture exactly what makes one building iconic and the other just awkward.

Part of the problem is scale. Rabid urbanisation means that some 529m Chinese (41% of the population) already live in urban areas, and the much-trumpeted intention was to build 400 new cities of 1m inhabitants each by 2020. Planners [architects?] are overworked. Albert Chan, architect with Chinese developers Shui On Land, admits that “the Chinese planner will work on an average of 10 projects a year. There’s no time to think, so they copy Europe’s style of architecture,” which some have dubbed 'Eurostyle'.

CCTV was not a cheap building, but its symbolic value is effectively priceless. Compared to the 300 or so conventional high-rises that cluster about it to form Beijing's Central Business District, and the traditional criticisms of iconic architecture - that it's superficial and attention-grabbing - seems rather redundant. In an instant cityscape, you have to stand out in order to make any impact whatsoever. It's a lesson that Chinese developers and designers have learnt, albeit with varying degrees of success.

Right now, it remains to be seen which way the Chinese design dream will go. There are enough innovative schemes on site to maintain the momentum kick-started by Koolhaas. But should funding start to slip away from the fantastical and start favouring the mundane, the return to the bad old days of Soviet-style system building and International Style knock-offs will swiftly put paid to the New Chinese dream of an architectural utopia. CCTV might point the way forward, but the road ahead is still shrouded with smog.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Clare Dowdy is a London-based freelance design and architecture journalist who has written for titles including Wallpaper*, BBC, Monocle and the Financial Times. She’s the author of ‘Made In London: From Workshops to Factories’ and co-author of ‘Made in Ibiza: A Journey into the Creative Heart of the White Island’.