It’s never been easier to go somewhere, but at the same time, it’s also never been harder to say why. As the most well-travelled generation in history, we can effortlessly book a trip to the other side of the world to eat the same poke bowl we had last weekend in Shoreditch, or lie under the same rattan pendant lamps as our friend in Uluwatu.

Where we once made journeys of discovery, we now book hotels and restaurants based on their Tripadvisor ratings, curated by algorithms and optimised for convenience. And what used to be full of uncertainty – missed trains, misread menus, unfamiliar etiquette – has become safe and predictable: language barriers vanish with Google Translate, and the best flat white within 100m has already been bookmarked. The more streamlined the experience, the less space there is for meaning. The joys of getting lost, of wandering aimlessly and ending up somewhere unplanned, have been engineered out in favour of efficiency, and spontaneity has been stripped away by meticulously planned itineraries, leaving little room for genuine discovery.

The thrill of stumbling across the unexpected has been replaced by comfortable inertia, and we now move through the world with little challenge, resulting in journeys that can easily become forgettable. And the irony is that, even as we accumulate more miles and more stamps, we’re not necessarily accumulating more insight. For all this hyper-mobility, there’s a nagging hollowness, which is precisely why place matters now more than ever. And the places that truly matter are the ones that provoke, confront, make us think, and linger long after the journey ends. What we need is not ease, but resonance.

Before it became something to document, travel was something to feel. You didn’t go away to check in with the world, but to step out of it. For writers such as Graham Greene, Paul Theroux and Norman Lewis, travel wasn’t a lifestyle; it was a way of being. In Greene’s 1936 memoir Journey Without Maps, which documents his four-week walk across Liberia, he says he discovered in himself ‘a passionate interest in living’, while in a 1979 Washington Post interview, Theroux noted ‘travel is only glamorous in retrospect’. For them, it was about dislocation, discovery, and the art of being unmoored, of sitting in a smoky café in Saigon for three days waiting for someone who might or might not show up, or spending a night in a town you couldn’t pronounce because the last bus had already left.

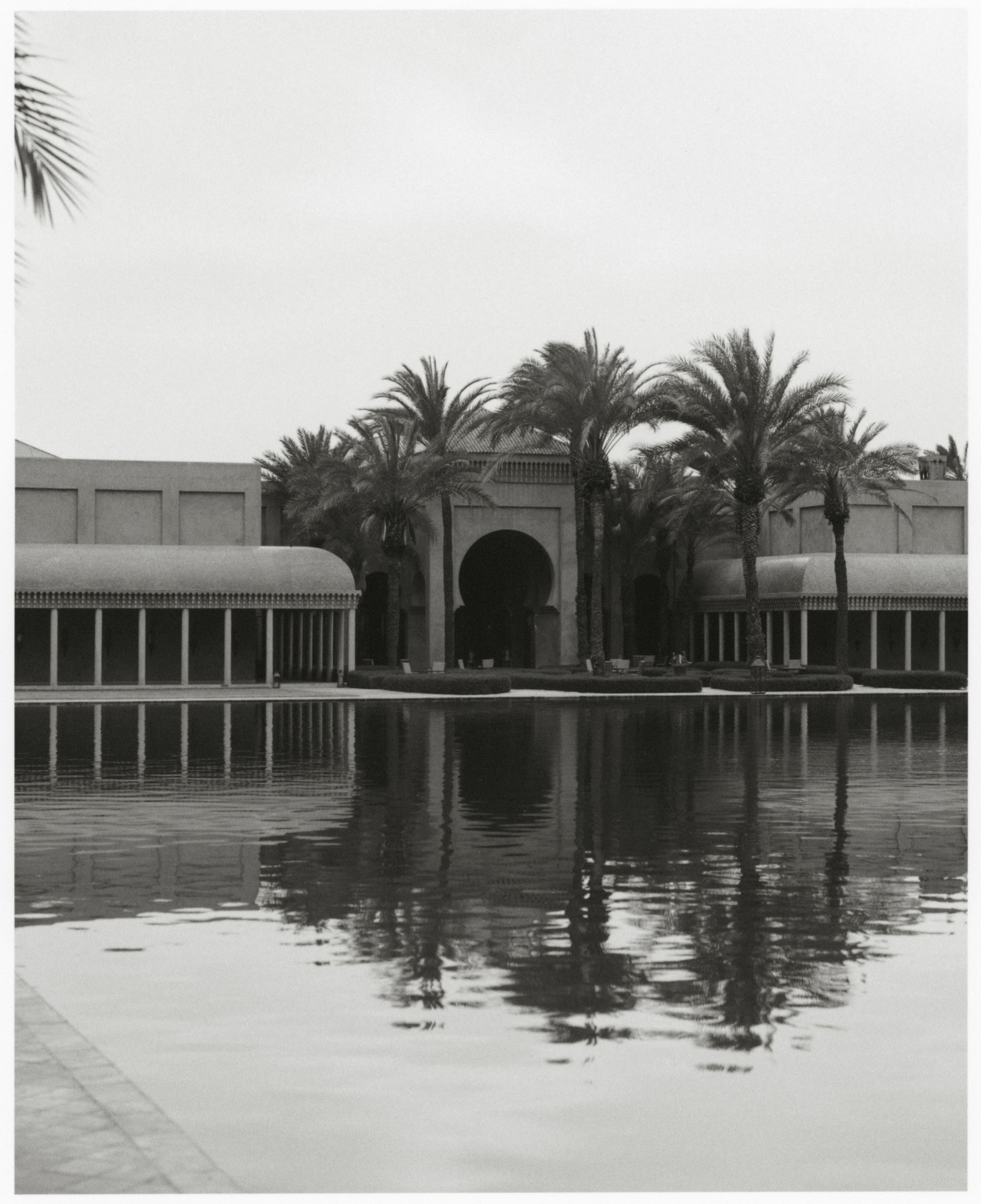

Their reasons weren’t always pure – this was a particular kind of travel, shaped as much by privilege, ego and agenda as it was by curiosity – but the way they travelled was slower, quieter and less concerned with being seen. Even the discomfort had value. You learnt to wait, watch, listen and be present, but, more importantly, you learnt about other people, how they lived and what mattered to them. To say you’d ‘done’ a city would have sounded absurd. A place was not a task to complete, but an experience to be shaped by. You didn’t just go to Marrakech, you were the sort of person who went to Marrakech. Back then, travel wasn’t performative; it was personal. There were no audiences, just the thrill of being somewhere that didn’t care you had arrived. And somehow, over the years, we haven’t lost the ability to move, but instead the willingness to be moved by what we see.

Resonance itself is not easy to define. Subjective but not random, it’s a personal response shaped by where you are emotionally and mentally. And while it might not make sense in the moment, it’s the type of emotion that, on reflection, unsettles, reorients and expands. The strongest places imprint slowly. Sometimes it’s visual, like a brutal skyline, an unexpectedly vast horizon or the strangeness of a landscape. Other times, it’s harder to trace, from a scent you can’t identify to an interesting conversation with a stranger that sits with you for days.

This is why resonance has less to do with beauty and more to do with texture – small differences that remind you that life is inconsistent and often contradictory. Resonance also comes from context. To begin to understand a place, you need to tune into its rhythms and pay attention to its edges. In Uzbekistan, for example, people still pay street vendors to weigh them – an easily missed detail that highlights the country’s enduring habits of practicality and informal entrepreneurship. These quiet signals rarely appear in guidebooks, but are often what form the foundation of what a place comes to mean to you.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

These aren’t so much stories in the traditional sense; rather, they are fragments that are incidental, routine or easily overlooked. But they accumulate and, over time, they form the scaffolding through which places begin to register. The ones that resonate tend to be those that don’t adjust themselves for you, but instead ask you to adapt, which, in doing so, allows you to notice more.

Naturally, there are moments when a place confronts you immediately, not because it’s spectacular, but because it exposes its workings so clearly that you can’t help but take notice. It might start with a minor inconvenience, like trying to get a taxi in Dakar and realising there’s no meter. The price isn’t fixed – instead, it’s negotiated in an interaction you can’t disengage from. This requires you to participate in a process that insists on presence and, as a result, pulls you, willingly or unwillingly, into a place’s everyday reality.

Then there are destinations that upend your expectations before you’ve even arrived. Much of what many people think they know about Saudi Arabia, for example, is shaped by headlines and hearsay. At first, the unfamiliar social codes can feel intimidating, especially the sight of women in niqabs, which, like a visual barrier, can be easy to misread as unapproachable. But once you look past this, you realise the focus becomes entirely about eye contact, creating a directness and a sense of connection that makes the interaction feel more human. The welcome is genuine, the generosity instinctive, and the conversations – if you’re open to them – are candid, curious and often full of humour. You quickly learn that hospitality here is not a performance, it’s a way of being. Coffee and dates, for example, aren’t just a gesture; they are a ritual offered to everyone as a simple act of inclusion.

And sometimes meaning comes not from contrast, but from coherence. In Japan, at the end of each Shinkansen train journey, a team of cleaners boards and tidies in under seven minutes. But what’s striking isn’t just the speed or efficiency, it’s the way they line up on the platform before boarding, bow to the waiting passengers, and then begin. It’s a quiet cue that life here runs on respect, not enforcement. The same instinct plays out in workplace car parks, where early arrivals often leave the closest spots empty so those who come later, potentially in a rush, don’t have as far to walk. It’s a small, unspoken courtesy, but one that says everything about the consideration at the heart of Japanese society. And for the traveller paying attention, it’s exactly the kind of detail that will tell you more than a guidebook ever could.

In Uzbekistan, people can come across as abrupt at first. Strangers might ask your age, marital status or how much you earn. There’s no soft entry and no small talk, which can feel intrusive if you’re used to more buffered social norms. But interact a bit more and you realise that it’s not rudeness, but rather direct and unfiltered curiosity. In a place where family, stability and social roles carry real weight, these are the questions that matter, and once you stop interpreting it through your own lens, it starts to make sense. It might not be warm in the way you expect, but it’s honest, which, in its own way, is a form of welcome.

But resonance isn’t reserved just for the remote or unfamiliar. Some of the world’s most visited cities still have layers that will reveal themselves if you choose to take note. In New York, if you look past clichés like Times Square, Broadway shows and pizza slices, you might discover the Jamaican beef patties tucked inside coco bread that reflect the city’s Caribbean communities. Or you might find that the best view isn’t from the Empire State Building, but of Manhattan Bridge at dusk from Brooklyn’s Dumbo neighbourhood.

In Hong Kong, it’s realising that 40 per cent of the city is protected parkland, and that you can hike an hour from Central, swim off a beach with no high-rises in sight and still be back in time for a Michelin-starred dumpling lunch. Beijing is often framed as fast and unrelenting, but in the summer months, one can witness the ‘Beijing bikini’, where men of a certain age roll their T-shirts up over their bellies – not for style, but relief in the incessant heat. For all its modernisation, China’s capital city surprises in the quietest ways if you just slow down and observe.

‘Meaningful travel leaves you sharper and more attuned to what you didn’t know you didn’t know’

In a world shaped by globalisation, many destinations have been smoothed over into something familiar. These days, you could land in a new country and still find the same industrial lights hanging over terrazzo counters, matcha lattes served in ceramics by staff wearing leather aprons, or hotel rooms with Diptyque bathroom amenities, a Dyson hairdryer and organically-shaped furniture in varying neutral shades. The language might change, but whether you’re in Mexico City, Melbourne or Lisbon, the mood has been copied and pasted.

And while polished and easy on the eye, it’s the kind of cautious experience that appeals to everyone, but speaks to no one in particular. The rough edges and small points of difference that once made a place distinctive have now been ironed out in the name of comfort. Over time, this kind of seamlessness can start to feel uninspiring, and with every experience blurring into the next, it’s easy to slip into autopilot and go through the motions without ever feeling like you’ve arrived. When everywhere starts to feel like anywhere, understanding why a place matters becomes more important than ever.

Beyond aesthetics, destinations are being reshaped not just by design trends, but by demand, and the very act of visiting en masse is starting to displace the qualities that made these destinations worth visiting in the first place. The recent coordinated anti-tourism protests across southern Europe have been a clear indication that mass tourism is no longer sustainable. Barcelona, a city of 1.6 million people, now attracts more than 30 million tourists a year.

The result is a housing crisis driven by short-term rentals, congested public infrastructure, and a city centre hollowed out by tourist traps selling fridge magnets and sub-standard paella. In Venice, locals now make up less than 50,000 of the city’s population, which is less than half of what it was just a generation ago. Mass tourism has distorted the experience of the place itself, where entire districts risk becoming stage sets, and visitors consume a version of a city that no longer exists for the people who built it.

These protests are about identity; it’s what happens when a city stops functioning as a home and becomes only a destination. This is not about anti-travel but is instead rooted in a desire to preserve what makes a destination worth visiting. This requires travellers not just to pass through, but to pay attention to the fact that cities are not just backdrops for leisure – they are living, working ecosystems.

This is why understanding a place matters. Because when a destination feels like it could be anywhere, the impulse to treat it as disposable grows stronger. But when you understand it – how it works, what it values, what it’s grappling with – you see it differently. And in turn, you behave differently, ultimately leaving a footprint, not of consumption, but of consideration. And in a world where context is being eroded by uniformity, reclaiming it has never felt more urgent. To travel meaningfully is to let go of certainty and allow a destination to unfold at its own pace.

You won’t always understand what you’re seeing – you might feel out of context or uncomfortable – but embrace that and you will see it as a joy to experience the world on its own terms. Meaningful travel doesn’t flatten or extract – it lingers, challenges, and leaves you sharper and more attuned to what you didn’t know you didn’t know. Because the point of travel is not to escape the world but to engage with it more deeply. At its best, it’s not about consumption but connection, and if we let it, travel can recalibrate not just how we see a place, but how we understand ourselves within it.

This article appears in the October 2025 Issue of Wallpaper*, available in print on newsstands, on the Wallpaper* app on Apple iOS, and to subscribers of Apple News +. Subscribe to Wallpaper* today

Lauren Ho is the Travel Director of Wallpaper*, roaming the globe, writing extensively about luxury travel, architecture and design for both the magazine and the website. Lauren serves as the European Academy Chair for the World's 50 Best Hotels.