Irys is an app designed by photographers for photographers. We take it for a test run

Irys celebrates the art and quality of photography, along with the joy of discovery. We discuss the nature of online creativity and the artlessness of social media with founder Alan Schaller

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Cast your mind back to the early days of Instagram and what a revelation the site seemed to be. Other than a few specialised sites like Flickr, 500px and DeviantArt, photographers didn’t really have an online space to showcase their work to a wider audience. Debuting in 2010, the app’s fascination lay in its square, Polaroid-esque format and array of aggressive filters. It wasn’t long before the creative community embraced the way Insta likes, shares and follows helped build followings and even make careers.

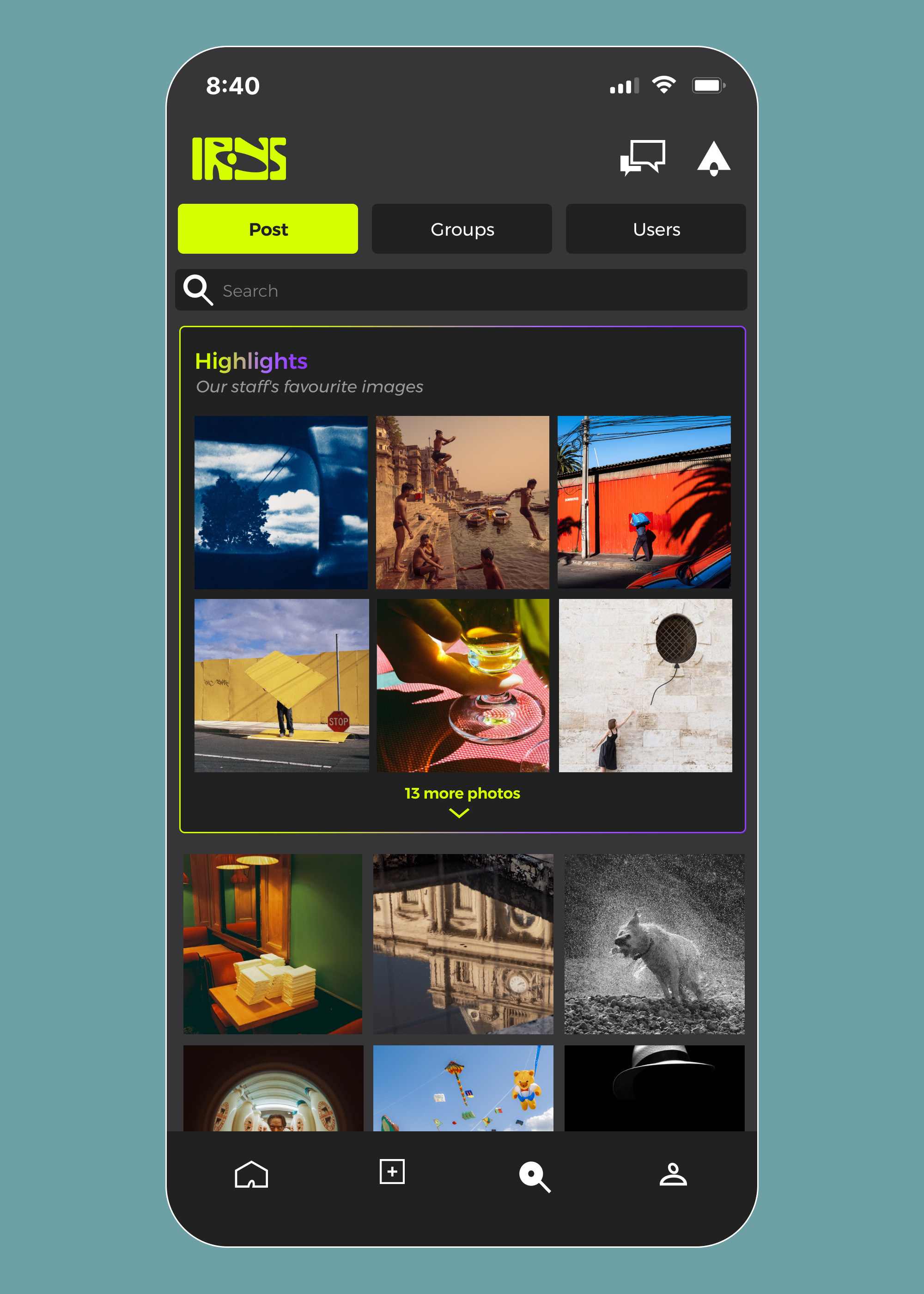

The explore page on Irys

For photographer Alan Schaller, those early years of Instagram had a certain purity to them. Late to photography, after first training and working as a commercial songwriter and musician, Schaller picked up a camera at the age of 25 and found an aptitude, especially for street photography. ‘Photography is the opposite of music,’ he says. ‘It’s instant and non-collaborative.’ His work got noticed online and commissions flooded in. As well as his own substantial one million-plus following, Schaller set up Street Photo International, which has over 1.7 million followers.

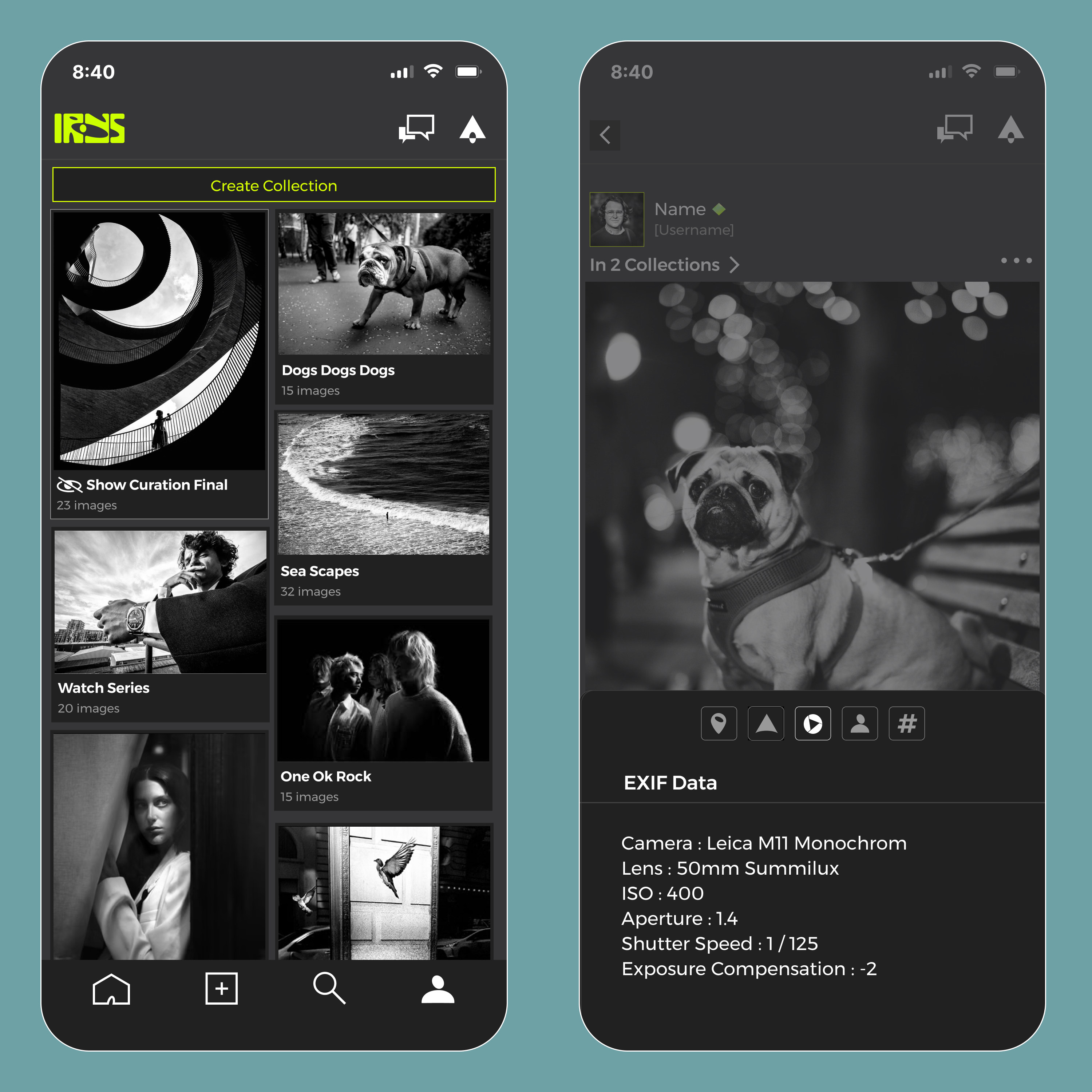

A preview of the collections page

And yet year on year, Insta delivered less and less. The advent of reels in 2020 saw the now Meta-owned site pivot hard to video content. Before this, SPI was getting around 40k submissions a day. With the advent of video, Schaller, like many other photographers, maintained his social presence but felt that the app’s appeal to pure photographers was waning.

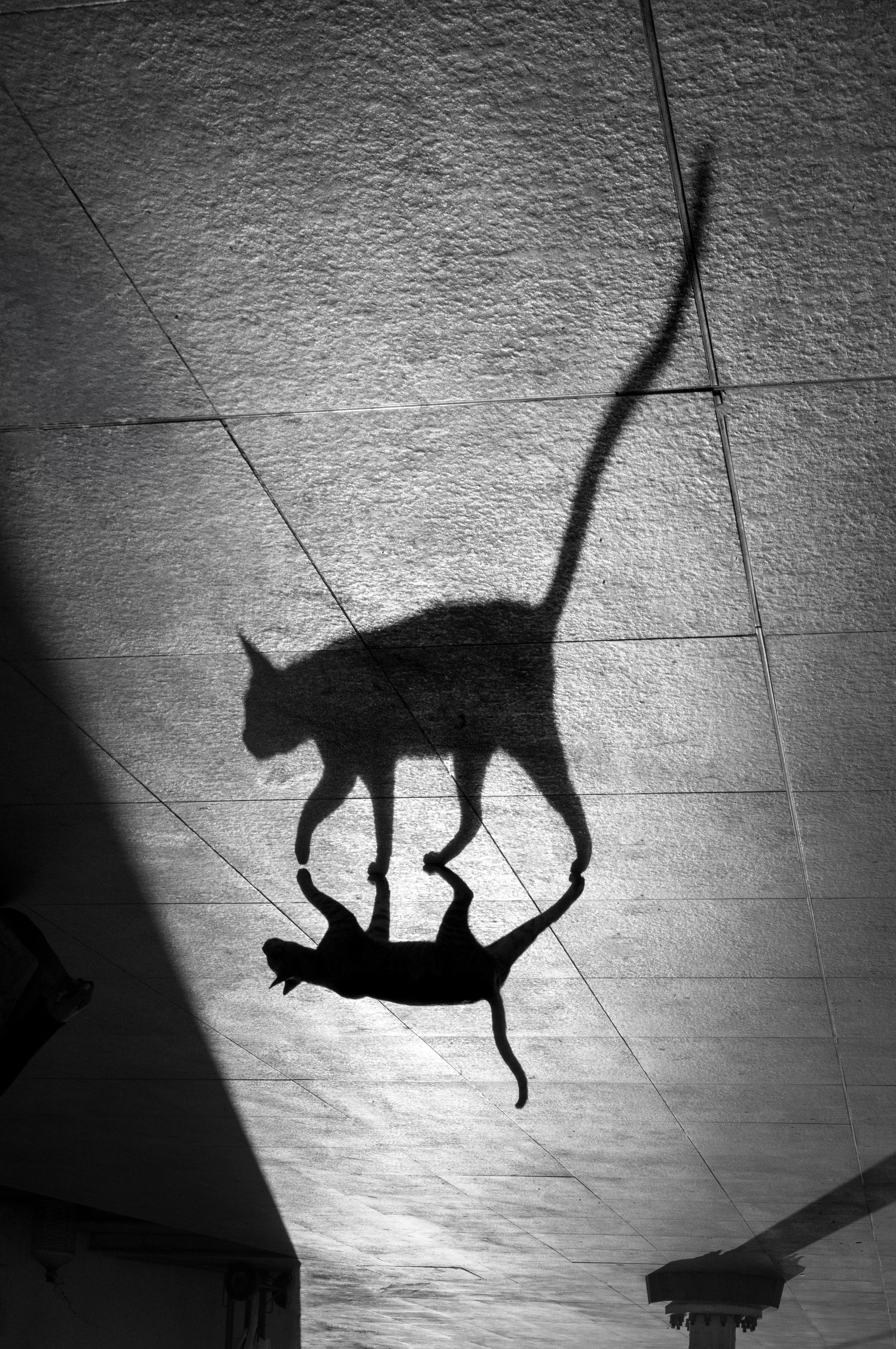

Some pivoted to video, but Schaller – who made his name with crisply observed and beautifully framed black and white imagery – felt this was ‘madness – this isn’t how creativity should work. Why should we expect tech companies to care about the photography world?’

Photographs can be viewed fullscreen (photographer: Josh Edgoose)

Instead, Schaller set out to create his own platform, assembling a team of photo industry players and taking on the role of CEO. The seeds of Irys were sown, just in time to tap into the current resurgence of all things photographic – not just phone photography, but dedicated cameras and even analogue film.

According to Schaller, Irys is a platform designed to actively celebrate the art of photography, not video, reels, memes or, heaven help us, AI. With a design partly inspired by the traditional photographic monograph, Irys will be familiar to anyone who’s tapped into a social media app over the last decade, only with a few key differences.

A photograph by Alan Schaller, founder of Irys

For a start, it’s curated by humans, not algorithms. Pictures aren’t compressed or cropped and you, the photographer, decide how best to display them in your portfolio. There are also no collections of filters or editing functions.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Irys offers the chance to browse and discover other people’s work, not have it pushed towards you algorithmically, with ‘collections’ set up to collate like-minded subjects, approaches, styles or whatever takes your fancy. Whereas one unthinkingly signs away all sorts of things when agreeing to a tech giant’s Ts and Cs, Schaller is adamant that everyone on Irys retains their image rights.

A photograph by Avani Rai, an Irys member

The team at Irys has already made solid partnerships with key camera brands, including Leica, Sigma and FujiFilm, reckoning that an eco-system that supports creators, promotes hardware and is committed to the industry is good for everyone. A basic account is free but naturally there are paid tiers. ‘We decided not to sell ad space,’ says Schaller, pointing out that Instagram has around 2.4 billion monthly users and that if just a tiny fraction of that number – less than 0.01 per cent – subscribed to Irys then the platform would be self-sustaining.

A photograph by Irys founder Alan Schaller

Naturally, you can like and follow photographers and images you admire, adding ratings across a number of different categories including composition, use of colour, etc. Your follower numbers aren’t made public, to avoid the inevitable popularity arms race that characterises other platforms.

‘It’s a more thoughtful space,’ says Schaller. ‘It’s not about attaching numbers to art. We want people to go on Irys and see great photography.' The Irys slogan, ‘This is what community looks like’, will also be extended to a new monograph publishing venture, Irys Publishing, and hopefully even a magazine.

An example of profile pages on Irys

It's a bold play to stand up to the dopamine dealers and create a platform that actively discourages doomscrolling in favour of more considered, focused browsing. But based on Schaller’s personal and professional experience, large swathes of the photographic community are not about chasing clout, obsessing over gear and going viral.

Irys recaptures something of Instagram’s early enthusiasm, spliced with the archival capabilities of Flickr, an isolated patch of quality amidst a raging sea of ever-changing imagery. For photographers and photography lovers, it’s a fine place to start exploring.

Irys is available for iOS and Android. Visit Irysphotos.com to download the app at the Play Store and App Store. @IrysPhotos, @Alan_Schaller, @StreetPhotoInternational

Jonathan Bell has written for Wallpaper* magazine since 1999, covering everything from architecture and transport design to books, tech and graphic design. He is now the magazine’s Transport and Technology Editor. Jonathan has written and edited 15 books, including Concept Car Design, 21st Century House, and The New Modern House. He is also the host of Wallpaper’s first podcast.