Tree houses: rural retreats reaching new architectural heights

Tree houses are havens for play and imagination, synonymous with youthful escapism and never-ending holidays. In tree canopies across the world, architects are hoisting up houses to broaden their horizons of minimal living and to experiment with timber construction that is sensitive and respectful of its environment. From eyries in upstate New York to leafy hideaways in Berlin and ‘eco-tourist’ hotels in Scandinavia, these tree houses will leave you pining. Branch out and get rooted…

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Evans Tree House

Modus Studio

Hot Springs, Arkansas

The Evans Tree House is the first of three to be installed at the Garvan Woodland Gardens in Arkansas. With hillside views of the Ouachita Mountain range and Lake Hamilton, the dendrology-inspired tree house is geared to reconnect young people with the outdoors. ‘From design to fabrication we were able to merge our childhood-earned knowledge of the natural world with our hard-earned ‘think, make, do’ philosophy,’ says Modus studio. The slatted structure is comprised of 113 fins made of locally sourced Southern Yellow Pine, creating numerous semi-transparent levels that ‘refocus attention to the natural wonders of the forest canopy.’

Paarman Treehouse

Malan Vorster

Constantia, South Africa

Drawing on the timber cabins of Horace Gifford, Kengo Kuma’s ‘notions of working with the void or in-between space’, Louis Khan’s ‘mastery of pure form’ and ‘the detailing ethic’ of Carlo Scarpa, Paarman Treehouse is an amalgamation of architectural inspiration. The one-bedroom treetop hideaway is located on its owners’ estate outside of Cape Town, in a small clearing on a high-up slope. Scaled to the height of the nearby trees, the three raised levels provide unrestricted views of outstanding natural beauty, accompanied by open, light interiors that resonate with the surroundings.

As originally featured in The Anatomy of Treehouses, by Jane Field-Lewis, published by Pavilion Books. Photography: Adam Letch

Paarman Treehouse

Malan Vorster

Constantia, South Africa

The square interior floor plan is framed by an exterior circle, creating a ‘pinwheel’ layout that winds up to the treetops. Each volume (constituted from branch-like columns, arms and rings) is made from Corten steel plating, with a protective oxide coating. Inside, the living room is located on the first level, accompanied by a patio, dining alcove and stairway; a bedroom and bathroom on the second level; and a roof deck and built-in seating on the third level.

As originally featured in The Anatomy of Treehouses, by Jane Field-Lewis, published by Pavilion Books. Photography: Adam Letch

4Treehouse

Lukasz Kos of Kos Architects

Walker’s Point, Canada

This vertically stacked tree house is permeated and supported by four trees, which wind through the build to create a link between the forest and the architecture. A lattice-like skin envelopes the trees, filtering sunlight into the interior spaces during the day and taking on visuals reminiscent of a lantern come nightfall, the internal lighting giving it a floating, beacon-like quality. The three levels heighten the relationship to the canopy, each providing individual and unique experiences with their surroundings.

Photography: Lukasz Kos

4Treehouse

Lukasz Kos of Kos Architects

Walker’s Point, Canada

Due to the sensitive nature of the build incorporating the plant life, it was important to ensure the health and growth of the trees was prioritised. A traditional ‘Muskoka balloon frame’ provides weight relief for the construct, allowing for only one particularly strong steel cable to be attached to each tree so as to minimise impact on the growing trunks. These cables suspended two Douglas fir beams, which create two large-scale swings from which the balloon frame sits.

The 7th Room

Snøhetta

Harads, Sweden

Snøhetta designed one of the rentable tree houses at the Treehotel site in Sweden, raising their build 10m up into the pines to provide a panoramic view of the Lule River. The underside of the tree house is covered by a life-size photograph of the treetops prior to the installation of The 7th Room, a nod to the site’s past and a reminder of Treehotel’s commitment to sustainability and dedication to providing an environmentally friendly experience to its guests. Meanwhile, the building’s façade features a black, charred timber surface, a technique typically employed in ancient Japan to protect buidings against the elements.

The 7th Room

Snøhetta

Harads, Sweden

The 7th Room

Snøhetta

Harads, Sweden

The 7th Room features 75 sq m of living space, which can accommodate five people. It consists of two double beds, a bed sofa, lounge, toilets and bathroom with a shower. A unique feature is the patio space, which features a safety net through which a pine tree rises, permitting guests to stargaze and sleep outdoors in summer. Inside, minimalist Scandinavian wood, textiles and organic solutions bestow a simple characteristic to the space.

Half-Tree House

JacobsChang

Barryville, USA

Blissfully sparse inside and out, this treehouse-cabin was completed in a single weekend by its owners, who, at the time, were amateurs in their trade. Submerged in surrounding forestry, Half-Tree House’s exterior is treated with traditional Scandinavian pine tar, minimising future maintenance and allowing a degree of protection against the long, wet upstate New York winters. Inside, the floors and walls are painted white, providing a pleasing contrast with the dark exterior.

As originally featured in The Anatomy of Treehouses, by Jane Field-Lewis, published by Pavilion Books. Photography: Noah Kalina

Half-Tree House

JacobsChang

Barryville, USA

The site of Half-Tree House is found in an isolated area of a 24-hectare wooded property, without vehicular infrastructure, electricity and running water. Resultantly, the groundwork had to be completed by hand using shovels. Seemingly floating above the forest floor, the treehouse makes use of the nearby tree life to raise it above the ground. Sonotube footings were used to anchor the upslope corners, whilst Garnier Limbs fixed to two of the close trees distribute the structure’s weight.

As originally featured in The Anatomy of Treehouses, by Jane Field-Lewis, published by Pavilion Books. Photography: Noah Kalina

Inhabit, NY

Anthony Gibbon Designs

Woodstock, USA

Using the guiding principles of biomimicry (which ‘asks architects to think of a building as a living thing or living being’) as a starting point, Anthony Gibbon puts nature at the centre of his architectural practice – both in the materiality of his sustainable constructs and in preserving the sites of his projects. His Inhabit tree house, located in the Catskill Forest Preserve near Woodstock in upstate New York, embodies this adherence to his environmentally minded design ethos, made from sourced local FSC-certified cedar timber and surrounded by tree saplings upon completion.

As originally featured in The Anatomy of Treehouses, by Jane Field-Lewis, published by Pavilion Books.

Inhabit, NY

Anthony Gibbon Designs

Woodstock, USA

The early design of Inhabit was developed as a conceptual build – a geometric form amongst the organic forest. The exterior of bright, new cedar wood was selected for its colouring capabilities, toning down as time passes to blend with its landscape. Inside, Gibbon was intent on using as few standard right angles as possible. The floorplan became largely open-plan, with large-paned windows replacing certain exterior walls. A mezzanine level above the kitchen aids to maximise the rural views offered from the tree house’s vantage point.

As originally featured in The Anatomy of Treehouses, by Jane Field-Lewis, published by Pavilion Books.

Tree Top Studio

Max Pritchard Gunner Architects

Adelaide, Australia

Australian architect Max Pritchard designed this two level structure to function as a studio away from his heritage listed, elevated steel and glass house on the outskirts of Adelaide. Working to the principal that ‘designers should be able to build their creations’, Pritchard constructed the studio himself (excluding the electrical works). Due to the slope, access to the studio can be reached by a raised timber decked bridge with a curved timber decked path leading back to the main house.

Tree Top Studio

Max Pritchard Gunner Architects

Adelaide, Australia

The circular tower is wrapped in golden plywood sheeting, with hardwood battens covering sheet joints and expressing the timber frame structure of vertical wall studs and radiating roof beams. Inside, the repeated detail of pine plywood and hardwood battens can be found, including a custom-designed circular table. The internal heating and cooling is entirely natural, provided by the coastal environment during the summer and the low winter sun during the colder months.

Treehouse Solling

Andreas Wenning

Uslar, Germany

Rising from a forest pond on the outskirts of the town of Uslar in Lower Saxony, Treehouse Solling is surrounded by a plethora of fantastical forest imagery, including a small brook, an abundance of flora and fauna, an old forester’s house and hemlock spruce trees. Whilst carefully landscaped, the site has been developed into the perfect setting for the nature-loving clients. Access to the larch wood deck terrace is found at the water’s edge, which leads to the rounded tree house tower above the water.

Treehouse Solling

Andreas Wenning

Uslar, Germany

The two levels are independently accessed – the first through the main level door, whilst the second is reached via an exterior staircase. Both levels are equipped with loungers and benches (with storage space underneath), as well as electrical connections. During the day, occupants can observe the array of wildlife found both below in the water and in the adjacent meadows, whilst at night, a domed skylight provides the perfect opening to star gaze.

The Fincube

Studio Aisslingera

Ritten, Italy

Built in the rural Dolomites mountain range near Bolanzo in the South Tyrol, northern Italy, the technologically advanced Fincube could be the answer to the future needs of smart tourism and temporary living. The flexible, nomadic space is sustainable, low energy and, importantly, transportable – meaning it can be moved between differing backdrops without leaving a lasting impact to its resting abode, thank to a central raised base that displaces the minimum amount of soil. Additionally, a central touch panel controls the heating, lighting, window blinds and alarm system, and the roof can either be greened or have solar panels installed.

As originally featured in The Anatomy of Treehouses, by Jane Field-Lewis, published by Pavilion Books.

The Fincube

Studio Aisslingera

Ritten, Italy

The Fincube is triple-glazed and primarily made from wood, with horizontal layered slats enveloping the entire building. The interior, meanwhile, is lined with larch and Swiss stone pine, and is helical in form – one space leads into the next. This natural flow also provides each of the rooms with an exterior view, creating a similarly seamless connection with the landscape the Fincube finds itself in.

As originally featured in The Anatomy of Treehouses, by Jane Field-Lewis, published by Pavilion Books.

Treehouse @ The Wood

Jeremy Pitts

East Sussex, UK

Built in his own woodland space to ‘feel the tranquillity and the connection between the materials and the making’, British woodsman and craftsman Jeremy Pitts created his own tree house from various different aged timbers, sourced within a 15-mile radius of the build site in East Sussex. Crisp, minimal and seamless, the principally used wide-board English oak was selected for its organic and irregular qualities. The form is hand-crafted around a prefabricated shell of structurally insulated panels, assembled on top of sweet chestnut tree trunks. Designed with sustainability in mind, the prefabricated sections can be transported for on-site assembly by hand, looking to maintain environmentally sensitive locations. Lightweight aluminium screw-pile foundations support the tree trunks, which can be removed without trace. Additionally, the building’s open space under the base allows local flora to flourish, and provides animals shelter during extreme weather.

As originally featured in The Anatomy of Treehouses, by Jane Field-Lewis, published by Pavilion Books.

Treehouse @ The Wood

Jeremy Pitts

East Sussex, UK

Decked out as a functional hideaway, the inside of the tree house is fitted with built-in seating, a foldaway work desk/table and bunk beds, which can be configured in a number of ways. The upper bunk is accessed by a ladder, which is made in a traditional method with oak wedged ends to the rungs. Its underside is a panel of cleaved sweet chestnut lath that provides a naturally sprung base for the mattress. The internal walls are clad in Scots pine wall boarding painted dark indigo, whilst the floor, ceiling and built-in furniture are made of English oak boards. Two large sliding windows take advantage of the sloping site, which give contrasting views – one of the nearby clearing, the other of the tree canopy.

As originally featured in The Anatomy of Treehouses, by Jane Field-Lewis, published by Pavilion Books.

Under Pohutukawa

Herbst Architects

Auckland, New Zealand

This family home is located on the edge of a belt of forest in Auckland. Prior to construction, the site was 90 per cent covered in pohutukawa trees. Herbst Architects considered the thicket of mature trees in the home’s design, looking to reduce its environmental impact on the space. Resultantly, as few trees were removed as possible, with the outdoor spaces incorporating many into the landscape design.

Under Pohutukawa

Herbst Architects

Auckland, New Zealand

Wood is the most prevalent of the used materials. Lyrically, the home’s exterior is stained black and brown, giving it the sense that it was cut out of the copse of trees. The use of wood is further translated inside, with walls, ceilings and ‘cabin’ partitions detailed in the same light timber. An open-plan living, dining and kitchen space occupies the majority of the first floor, whilst two bedrooms above are accessed by a walkway linking the two tower-like volumes.

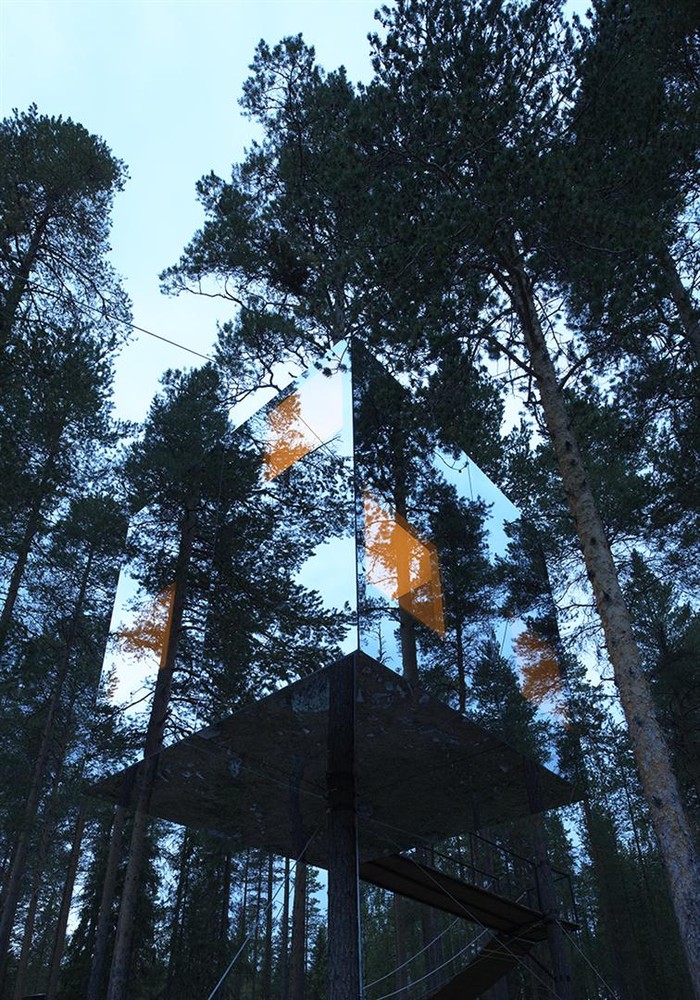

Mirrorcube

Tham & Videgård Arkitekter

Harads, Sweden

Tham & Videgård Arkitekter designed this 4m sq mirrored volume to join ecotourism hotel company Treehotel’s cluster of contemporary tree houses, located in the pine forest near the Lule River in Sweden. The simple tree hut is a lightweight aluminium structure mounted atop the trunk of a tall pine tree, clad in reflective glass that bridges the gap between modern construction materials and natural location. Most striking is the single tree that cuts through the central living space of the Mirrorcube, momentarily disappearing into the camouflaged construct before reappearing out the top.

Mirrorcube

Tham & Videgård Arkitekter

Harads, Sweden

The interior is made from plywood with a birch surface, and six windows provide panoramic views of the surroundings. Designed for two people the tree house features a double bed, toilets, lounge and rooftop terrace. Showers and a sauna are located in a separate building nearby. The tree house is accessible by a winding 12m bridge wraps around the nearby trees.

Yellow Treehouse Restaurant

Pacific Environments Architects

Auckland, New Zealand

In 2008, Yellow Pages developed a marketing campaign to highlight the variety of working practices found within the directory. Project leader Tracey Collins selected Pacific Environments Architects to design the Yellow Treehouse Restaurant, which sits around a 40m high Redwood tree. The open meadow below and nearby meandering river inspired a nature-driven design, which is reminiscent of a cocoon, seashell or onion clove.

Yellow Treehouse Restaurant

Pacific Environments Architects

Auckland, New Zealand

Timber trusses form the core structure, with curved fins of glue-laminated pine and plantation poplar used for the exterior slats. A 60m walkway provides access to the 30 guest restaurant, which sits 12m above the ground. Discreet lighting is found within the walkway and inside the tree house, giving the restaurant a completely different visual experience at night. It is now open for private functions only.

Urban Treehouse

Andreas Wenning

Berlin, Germany

For Andreas Wenning, this project presented the unique opportunity of designing a tree house within an urban environment. He wanted to show how a tree house could be modern, and how a small space could perhaps be more intimate and preferable to a larger space. Located at the border of the forest in the Zehlendor district in Berlin, the two 21sq m spaces are near to the Krumme Lanke and Schalachtensee lakes.

As originally featured in The Anatomy of Treehouses, by Jane Field-Lewis, published by Pavilion Books.

Urban Treehouse

Andreas Wenning

Berlin, Germany

The tree house’s main body is made of galvanised steel, while the walls, ceiling and floor are constructed from solid, prefabricated five-layer spruce panels. Both volumes have a covered terrace space flanked by stairs supported by flexible suspensions from a nearby oak tree. Ceiling-to-floor windows fill the interior space with light, and all necessary living facilities are contained. Both buildings are supported by a stand-type base lined with larch, which house the utilities and supply circuit and act as a storage space for gardening tools and waste.

As originally featured in The Anatomy of Treehouses, by Jane Field-Lewis, published by Pavilion Books

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Ellie Stathaki is the Architecture & Environment Director at Wallpaper*. She trained as an architect at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece and studied architectural history at the Bartlett in London. Now an established journalist, she has been a member of the Wallpaper* team since 2006, visiting buildings across the globe and interviewing leading architects such as Tadao Ando and Rem Koolhaas. Ellie has also taken part in judging panels, moderated events, curated shows and contributed in books, such as The Contemporary House (Thames & Hudson, 2018), Glenn Sestig Architecture Diary (2020) and House London (2022).