Peter Zumthor: from small town spa star to global campus king

Therme Vals was completed in 1996, the same year this magazine was founded. It was clearly a good year. Two decades on, Peter Zumthor’s genre-defining spa in the Swiss canton of Graubünden remains a place of pilgrimage for architecture enthusiasts the world over. And Zumthor is now one of the world’s most sought-after architects.

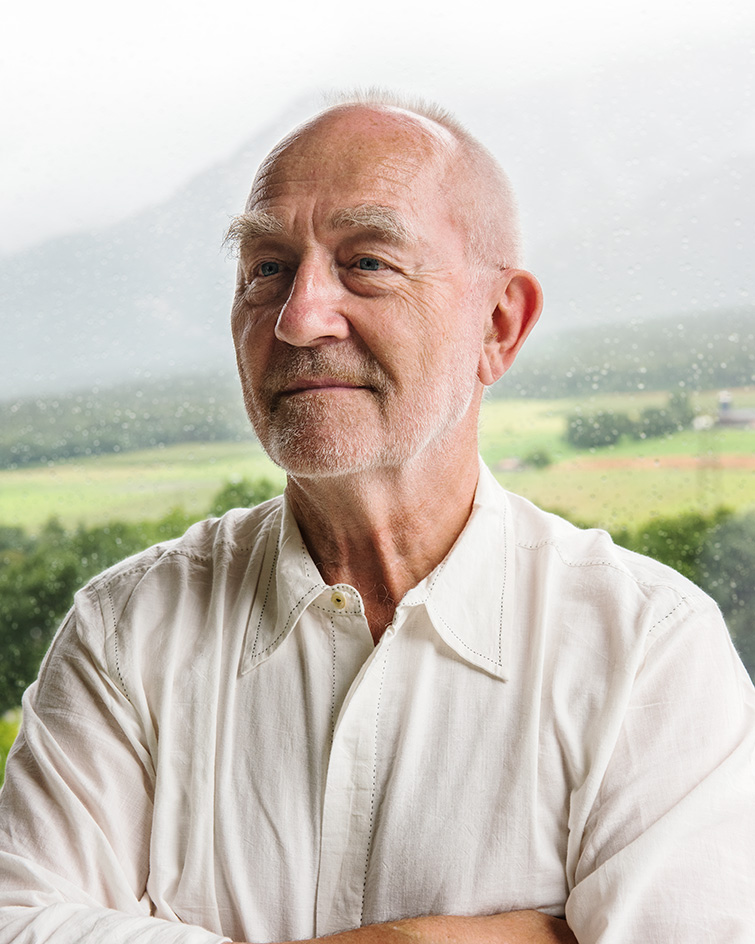

Peter Zumthor is not your typical internationally-operating, Pritzker Prize-winning architect, even if there is such a thing. He has no offices in London, New York or Zurich, preferring instead to base himself in the tiny Swiss hamlet of Haldenstein, where he has lived and worked for more than 40 years. At his atelier, staff are not found glued to shiny Apple Macs but gathered around physical models of buildings – working prototypes lifted up on stilts to eye level – while beyond those models, breathtaking wraparound views stretch out across the Grisonian Rhine Valley. The practice is small, deliberately limited to around 30 people, making it a necessity to be very choosy about the projects it takes on. Which is what makes it really different. Looking back over the last 20 years since Therme, the projects Zumthor has designed have been dictated not by commercial opportunity, but by where architecture can make a real difference to the human experience. Where architecture can bring joy, peace, insight or energy: you know you’re in a Zumthor building not because you notice any trademark shapes or materials, but because of how it makes you feel.

He originally came to Haldenstein in the early 1970s, then met his wife here and ended up staying. They bought an old farmhouse with some land, and over the years transformed it into their family home, and eventually the atelier. Now the atelier has the luxury of a new, additional building, which is currently being completed and which affords everyone some extra space – not to mention those incredible views over the valley.

Despite international demand, he says, they were never tempted to move. ‘Because I have to keep things concentrated because of the authorship of architecture. It’s very personal... I work like an artist. So this was a good place. I remember the moment when I thought from now on I would do my own thing. It was about liberating myself.’

Looking back, he says he can see that everything happened by chance: ‘The contingencies of life, you know, but there seems to be some kind of sense to them.’ In 1983, the village of Vals acquired a bankrupt 1960s hotel complex and, largely to rescue existing jobs, set up an architectural competition to design a new thermal baths as a first step towards its regeneration.

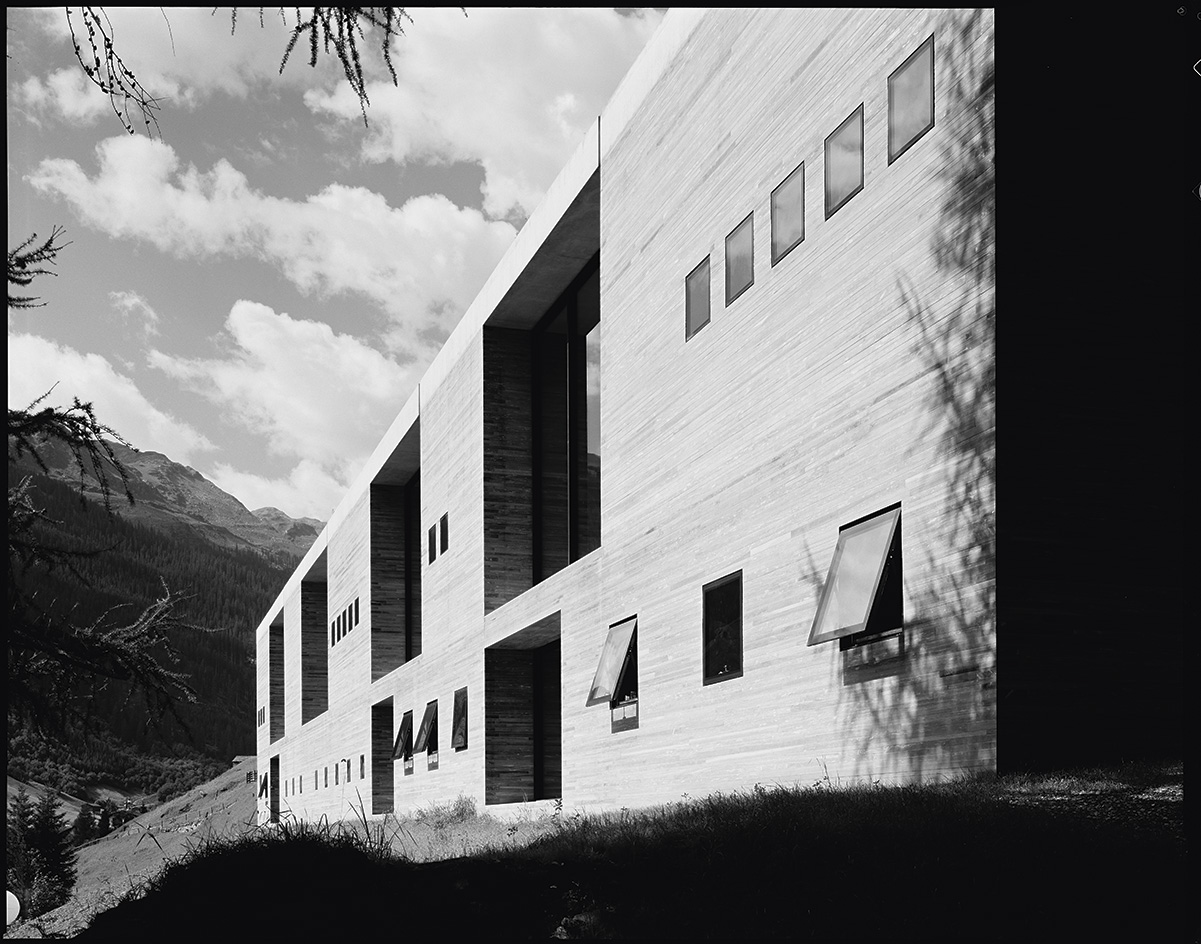

Zumthor, despite having a limited track record at the time, won the commission for his design, which resembles the foundations of an archaeological site, half buried in the hillside and constructed using local Valser quartzite slabs. Much has been written about the astonishingly beautiful results that have drawn over 40,000 people to visit every year since completion – and though the hotel itself, now under new ownership and renamed 7132 Hotel, continues to undergo changes and developments, the baths remain blissfully untouched, as ageless and enduring as the mountains around them.

Therme is just one project that has helped to foster Zumthor’s reputation for wellness architecture. Though its success could have seen him become the sparchitect of choice, Zumthor has avoided replica commissions, instead focusing on projects that allow a particularly unique architectural experience. The 1997 Kunsthaus Bregenz overlooking Lake Constance (Bodensee) in Austria, for example. Or his two completed projects for the wild landscapes of Norway’s National Tourist Routes. Or the serene Serpentine Gallery Pavilion in 2011. Or the much anticipated Secular Retreat in Devon, which promises to be the most inspired Living Architecture project yet. Or the teahouse in Korea that he’s currently designing. While the newest generation of architects is preoccupied with notions of wellness, mindfulness and the landscape, Zumthor has been refining the approach for decades.

But does he recognise himself as a pioneer? ‘This changes because there were years when everybody thought, “This guy is still working like this, he’s really old-fashioned, he doesn’t even look at what everyone else is doing”,’ he says. ‘But I’m not changing, I do my thing and it was always appreciated.’

His approach might not have changed, but over the years the nature of the commissions Zumthor has been invited to undertake have grown in scale from small residential projects to entire campuses, such as the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), due to complete in 2023. With his years of experience, he says, he’s learned not only how to step back from his work and reflect, but also to be ‘more professional’ in his dealings with the world. ‘How do I deal with people in Qatar or Norway? In the beginning I was just working; now I look at the people and try to make sure I’m not forcing them to do something I can see they can’t be bothered with, or which they’ll have a hard time doing.’ Perhaps most importantly, he says mischievously, he’s learned ‘how to get rid of a client in one day’, if he knows it’s not a match. ‘As a young architect I didn’t know how to deal with people, and now I do. It takes a long time to understand where you should engage and where not. I’m getting better.’

So are there any dream projects still on the horizon for Zumthor? ‘An auditorium for music,’ he says. ‘I’d like to do a couple of terraces or a whole neighbourhood, things like that are done very poorly now. Something on water… I’m not interested in skyscrapers, it’s not my cup of tea. A hotel in the Alps maybe… I love hotels, there hasn’t been a really nice beautiful hotel in a long time.’ Perhaps the next 20 years will be the best yet.

Peter Zumthor is one of our 20 Game-Changers. Read about the other 19 here

As originally featured in the October 2016 issue of Wallpaper* (W*211)

A view towards Therme’s grass-roofed outdoor pool with sunbathing terrace.

Therme was built using locally quarried Valser quartzite slabs.

Carefully positioned gaps in the ceiling and walls flood Therme’s indoor pool with shafts of light.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Henrietta Thompson is a London-based writer, curator, and consultant specialising in design, art and interiors. A longstanding contributor and editor at Wallpaper*, she has spent over 20 years exploring the transformative power of creativity and design on the way we live. She is the author of several books including The Art of Timeless Spaces, and has worked with some of the world’s leading luxury brands, as well as curating major cultural initiatives and design showcases around the world.

-

Apple Music’s new space for radio, live music and events sits in the heart of creative LA

Apple Music’s new space for radio, live music and events sits in the heart of creative LAApple Music’s Rachel Newman and global head of workplace design John De Maio talk about the shaping of the company’s new Los Angeles Studio

-

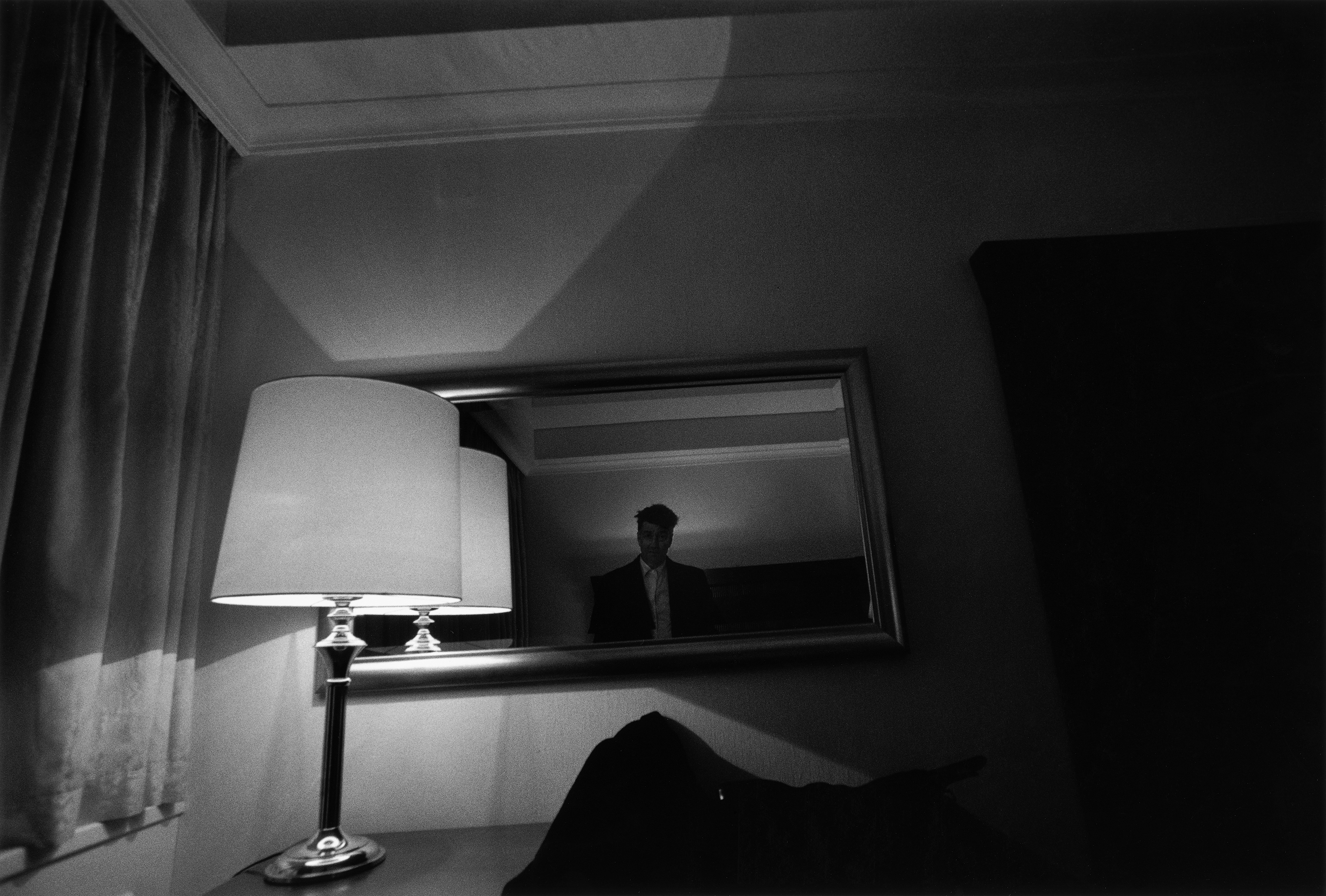

David Lynch’s photographs and sculptures are darkly alluring in Berlin

David Lynch’s photographs and sculptures are darkly alluring in BerlinThe late film director’s artistic practice is the focus of a new exhibition at Pace Gallery, Berlin (29 January – 22 March 2026)

-

Roland and Karimoku expand their range of handcrafted Kiyola digital pianos

Roland and Karimoku expand their range of handcrafted Kiyola digital pianosThe new Roland KF-20 and KF-25 are the latest exquisitely crafted digital pianos from Roland, fusing traditional furniture-making methods with high-tech sound

-

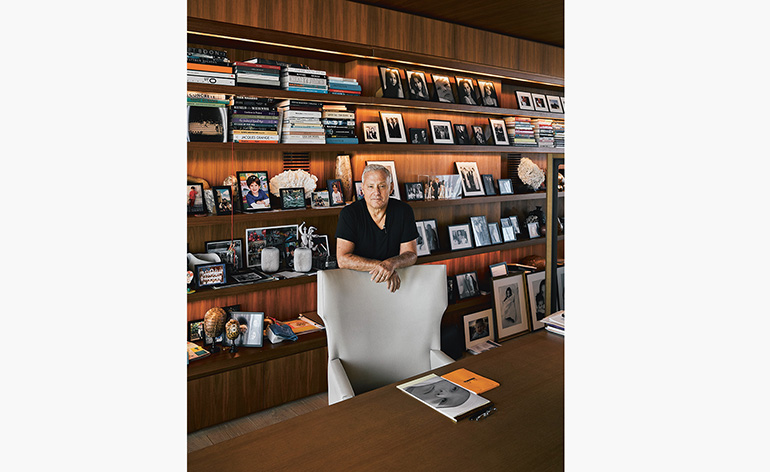

Host with the most: Ian Schrager is the visionary who revolutionised the hotel industry

Host with the most: Ian Schrager is the visionary who revolutionised the hotel industry -

Airbnb: from Couch Surfers to Big Friendly Giant

Airbnb: from Couch Surfers to Big Friendly Giant