The challenge was not nearly as daunting as it might sound: to find design and innovation in a district of Shenzhen once known as the counterfeit capital of the world.

Stretching about a kilometre and a half in central Shenzhen, Huaqiangbei has been the heart of the city’s electronics industry since the first factories set up there in the early 1980s. Now home to thousands of dealers, stacked and jam-packed in a labyrinthine sprawl, the area continues to churn out dodgy shanzhai (imitation) Apple and Samsung smartphones, alongside all the components you’d need for assembling one yourself. But Huaqiangbei is also looking increasingly like a hotbed for innovation, both big and small.

‘When you come here for the first time, your eyes open wide,’ says Henk Werner, the Dutch co-founder of Trouble Maker, an open start-up accelerator that recently set up shop in the area. Werner’s new space joins a thriving ecosystem of makers and hackers, entrepreneurs and venture capitalists, who are feeding off the region’s manufacturing prowess, quick turnaround times, and heaps of electronic components to concoct the next big thing. On a recent weekend, however, I had a less glamorous mission. As curator for M+, the new museum for visual culture being built in neighbouring Hong Kong, I was looking for what my colleagues at the V&A’s nearby Shekou project have aptly called ‘unidentified acts of design’, the often unsung outputs of processes that lie outside the design mainstream, but that in Shenzhen mark new systems of production that are reshaping the way we make and consume things.

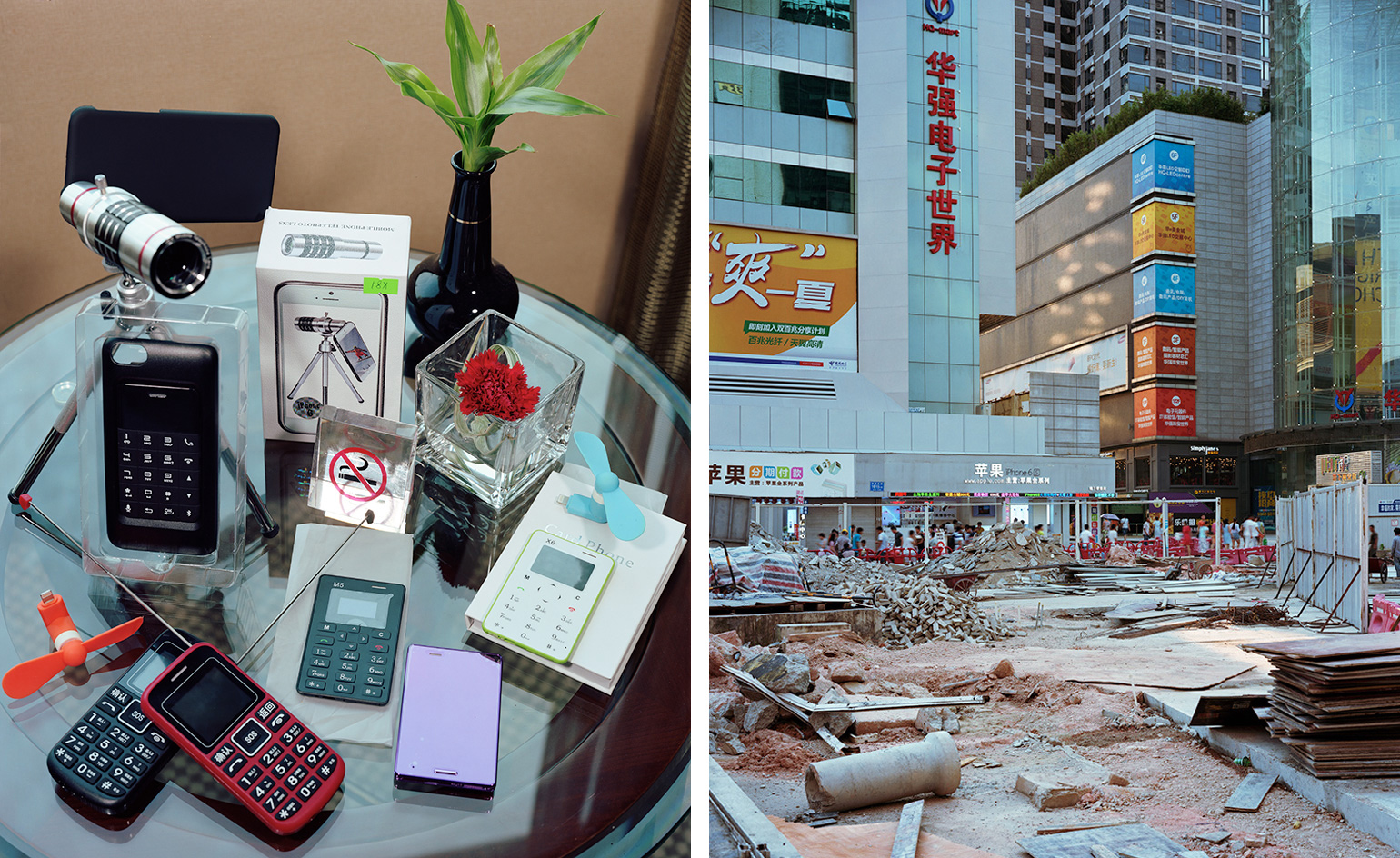

Dodging the drones and hoverboards that were zipping to and fro, I threw museological obsessions like provenance to the wind, and instead sought out phenomena. Looking beyond the city’s rapid-fire ability to mass-proliferate the latest trends, whether hoverboards (so 2015) or virtual-reality glasses (the latest thing), I decided to focus on ‘hybrid objects’, which intriguingly mix and match what’s existing and familiar — a kind of incremental, see-what-sticks innovation — in a way that perhaps only Shenzhen can.

Some examples I found pragmatically address under-served users: building on a widely cited large-button mobile phone for the elderly that started popping up some years ago, a new version, simply labelled Model K2, incorporates a flashlight and radio with retractable antenna. Others were more unwittingly evocative, like the mini-tripod that turns your smartphone into a telescope in an age of growing surveillance.

Somewhere in-between was the ‘card phone’, a credit card-sized mobile phone that looks like a cross between a bank security device and a pocket calculator. With a highly accessible starting price of RMB100 (about $15) in a country where average incomes are still relatively low, it has, since its introduction about two years ago, already generated versions in multiple candy colours and with tiny touchscreens. There’s also a model that snaps onto the back of your smartphone for those who need two numbers (as many migrant workers in China do), but don’t yet have a dual SIM card phone — the latter being another small but notable advance that’s been credited to Shenzhen’s ‘copyists’. Indeed, one begins to wonder where imitation ends and innovation starts.

At the end of my visit, I couldn’t help but pick up a few sheets of holographic stickers of the kind that are often affixed to packaging as a mark of authenticity. You see them everywhere around Huaqiangbei — ready to be applied to anything that one wants to label as an ‘original’.

As originally featured in the October 2016 issue of Wallpaper* (W*211)

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.