The final frontier: set for lift-off at Spaceport America with Y-3’s flight suits

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Richard Branson’s space tourism venture Virgin Galactic has partnered with Yohji Yamamoto’s Adidas label Y-3 to develop a range of bespoke flight suits for pilots and passengers. Pictured: Spaceport's ‘super hangar’, housing Virgin Galactic’s SpaceShipTwo

Watching Ridley Scott’s The Martian, it’s impossible not to be gripped by the frantic struggle of one man stranded in space, hundreds of thousands of miles from home. It’s also pretty hard to understand why the future of space travel is so ugly and ineffective. Dude, you’re in space. How hard is it to look good?

The answer seems to be: not that hard at all, provided you work with the right people. Richard Branson’s space tourism venture Virgin Galactic has partnered with Yohji Yamamoto’s Adidas label Y-3 to develop a range of bespoke flight suits for pilots and passengers. And they’ve made looking good a priority. As Lawrence Midwood, Y-3’s senior director of design, explains, astronauts and pilots should look like heroes.

‘The suit needs to be safe, bold, strong and confident, projecting security so the pilot looks like someone you’d trust taking your father on a daring trip,’ he says. The label’s sleek, black prototype suits are cut from a tough, flame-resistant hydrocarbon called Nomex, a material that’s a close relative of the body armour Kevlar. For Midwood, new materials are the key to future space apparel design.

‘We are on the verge of fabrics that can easily adjust to the climate and also the body’s microclimate – in the future we will develop a suit that helps you cope with any heightened emotions as well,’ Midwood explains. ‘The experience of space travel is an intensely emotional journey – if you start to feel tension or panic, your temperature rises and naturally you start to perspire. This suit would help to combat these physical reactions by helping to cool and therefore calm you during the flight.’

Health-monitoring apparel – already in use by sports teams – should come next, he expects, with a suit that is fully aware of how your body is coping throughout the journey and relaying the data accordingly. Possible future options for Virgin’s passenger suits include a system that allows your family and friends to track your journey and emotions throughout the flight to share the experience.

Space tourism is currently at the heart of space-age design. Launched in a blaze of glory back in 2004, Virgin Galactic aims to provide regular sub-orbital passenger flights from Spaceport America in the New Mexico desert. The company suffered a setback in 2014 when its first sub-orbital craft, VSS Enterprise, broke up during a test flight, killing one pilot and seriously injuring another. In February this year, the company rolled its second ship – VSS Unity – out onto the tarmac at Galactic’s Mojave Air and Spaceport HQ in California to begin months of ground testing.

Having laid out an ambitious timetable – Branson initially suggested the first flight could take place in 2009 – Virgin is loath to reveal future deadlines, although it’s possible to book a seat already for a cool £200,000, paid in full upfront. So far, some 700 people have booked, according to Virgin Galactic’s head of design Adam Wells. The price includes three days of astronaut training and a two-hour flight, with four minutes of weightlessness. It’s an experience rather than a mission – and the design of craft, suit and Spaceport reflect that.

Wallpaper* visited Spaceport America at the start of the year and was delighted to feel a certain theme-park excitement at the building’s careful hide-and-reveal strategy – as conceived by London-based architects Foster + Partners. The building’s main entrance seems to rise from the baked soil of the Jornada del Muerto desert basin, with a long, deep channel cut through banks of dry brown earth.

Huge steel doors suggest Nasa’s blast-shielded launch control centre back in the early days of the Apollo missions. Once through the doors, however, a glass walkway carries passengers through the main hangar, over the waiting SpaceShipTwo and its launch carrier WhiteKnightTwo before opening onto a huge glass wall, with the runway and desert sprawled outside. ‘We needed a bit of theatre,’ explains Grant Brooker, senior partner and project architect for Spaceport. ‘It’s the first commercial space hangar, after all....’

Flying in to land on Spaceport’s mile-long runway, however, you can already see the foundations being struck for competing terminals – with UP Aerospace and SpaceX Falcon 9R projects both under construction. As a result, there is a flurry of interest in space design from architects and designers – British studio PriestmanGoode has designed a capsule for US-based Paragon that will float six passengers up to the edge of space via a large helium balloon, offering views of the Earth’s curvature; Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner will serve tourists as well as Nasa; and Space Adventures Ltd plans a lunar landing in 2018 – it sold its first ticket for $150m.

And sub-orbital flight is just the first step. More than 200,000 people from 140 countries have applied for a one-way ticket to join a human settlement on Mars. Fortunately, there are alternatives underway to the rickety habitation that nearly killed Matt Damon.

Post-Spaceport, Foster + Partners has won design competitions with both the European Space Agency and Nasa to build bases on the moon and Mars respectively. The company’s plans revolve around 3D-printing technology, explains Xavier De Kestelier, partner and architect involved in the moon and Mars projects. His concerns were weight, safety and comfort. Instead of complex polyhydrocarbons, however, he chose mud. Albeit space mud.

‘It costs around £200,000 to send a single kilogram to Mars, so we plan on sending robot 3D printers to work with the soil already there,’ De Kestelier explains. ‘For the moon that’s three big robots but for Mars it would be about 50.’

De Kestelier spent time with the British Antarctic Survey to understand how people use confined spaces for long periods. ‘We ended up with surprisingly small private spaces – we found when people were reading a book, for instance, they would choose to do so in the shared area,’ De Kestelier explains. Wood and tactile surfaces help the interiors feel less sci-fi and more homely, with large screens for windows and skylights that can show the outside environment or soothing pictures of forests and oceans aimed at calming panicky astronauts terrified by how cut off from Earth they are.

All of which suggests sci-fi writers have had it all wrong for years. Instead of flashing, bleeping consoles, plastic surfaces and bright orange suits, we can expect wooden finishes, forest vistas, adobe cabins and fitted jumpsuits. Space, in other words, is going to look a lot like Sweden.

As originally featured in the April 2016 issue of Wallpaper* (W*205)

Pictured left: a breathtakingly space-age glass wall curves around one end of the building. Right: Lawrence Midwood, Y-3’s senior director of design, at the Spaceport

Pictured: Spaceport America's New Mexico hub, designed by Foster + Partners, is the world’s first commercial spaceport and is set to be the base for Virgin Galactic’s tourist flights

The Y-3 flight suits are tough, flame-resistant and, crucially, made to make one look like a hero

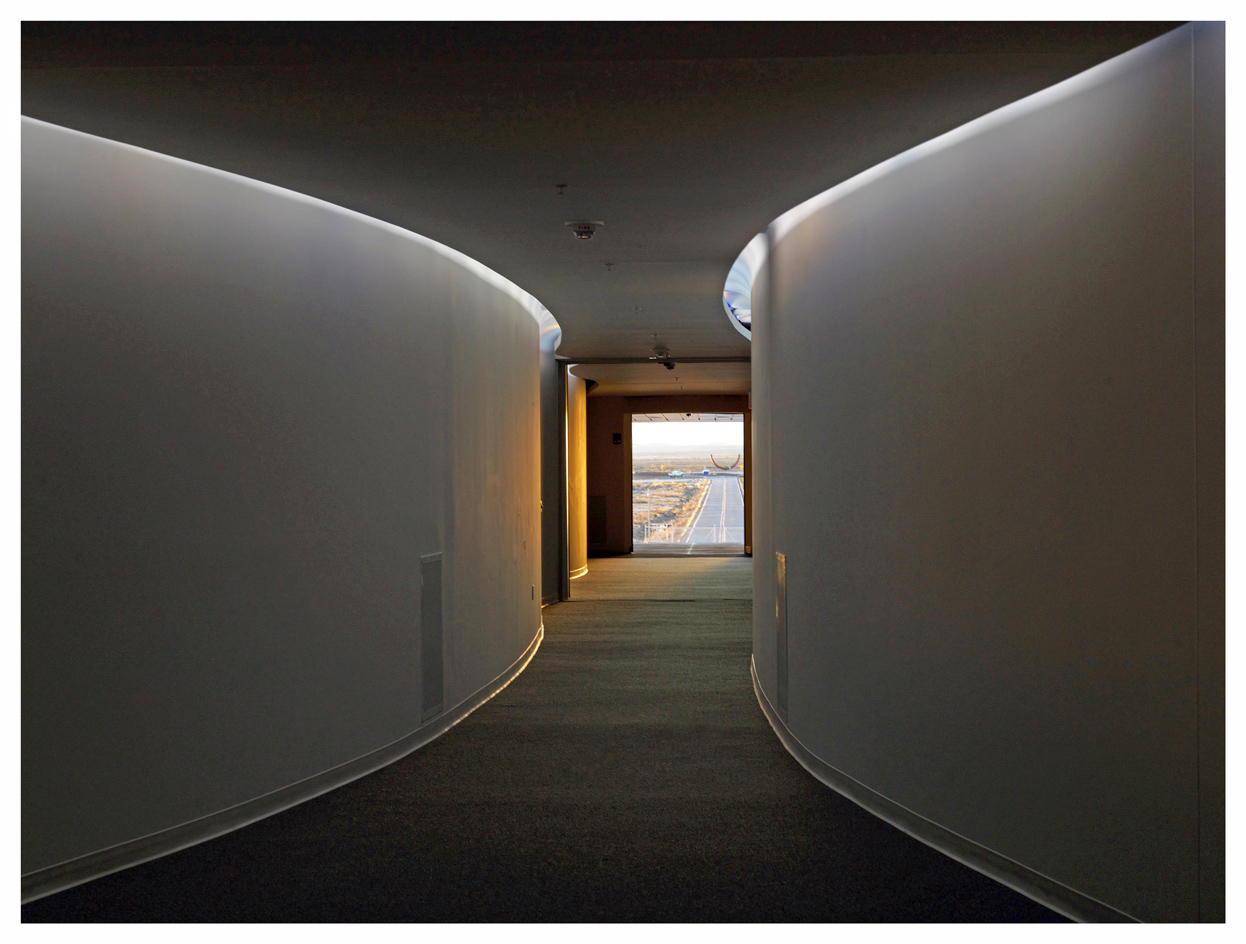

A view through the Spaceport’s interior – sleek, sinuous lines feature inside and out, capturing some of the cultural drama of space travel

Y-3's sleek, black prototype suits are cut from a tough, flame-resistant hydrocarbon called Nomex, a material that’s a close relative of the body armour Kevlar

INFORMATION

For more information, visit Virgin Galactic’s website

Photography: Vincent Fournie

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.