Yayoi Kusama stages a polka-dotted Wallpaper* takeover

As Japanese artist Kayoi Kusama swathes Wallpaper* October 2023 in inflatable, polka-dotted tendrils for her guest-editor takeover, cultural historian David Elliott explores the career of a global art pioneer

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Yayoi Kusama has devoted her life to the production of art for more than eight decades, and she retains the same intensity and concentration as when she started out in rural Japan at the end of the 1940s. Acknowledged globally as a pioneer of numerous art forms, including minimalism, immersive and pop art, performance, assemblage and installation, her artistic practice has spanned painting, drawing, sculpture, collage and film, as well as literature, fashion and product design. Two enduring and instantly recognisable motifs in her work are the pumpkin and the polka dot, both rooted in childhood experiences and hallucinations, but her output is prolific and expansive, her energy for art-making undimmed as she enters her ninth decade.

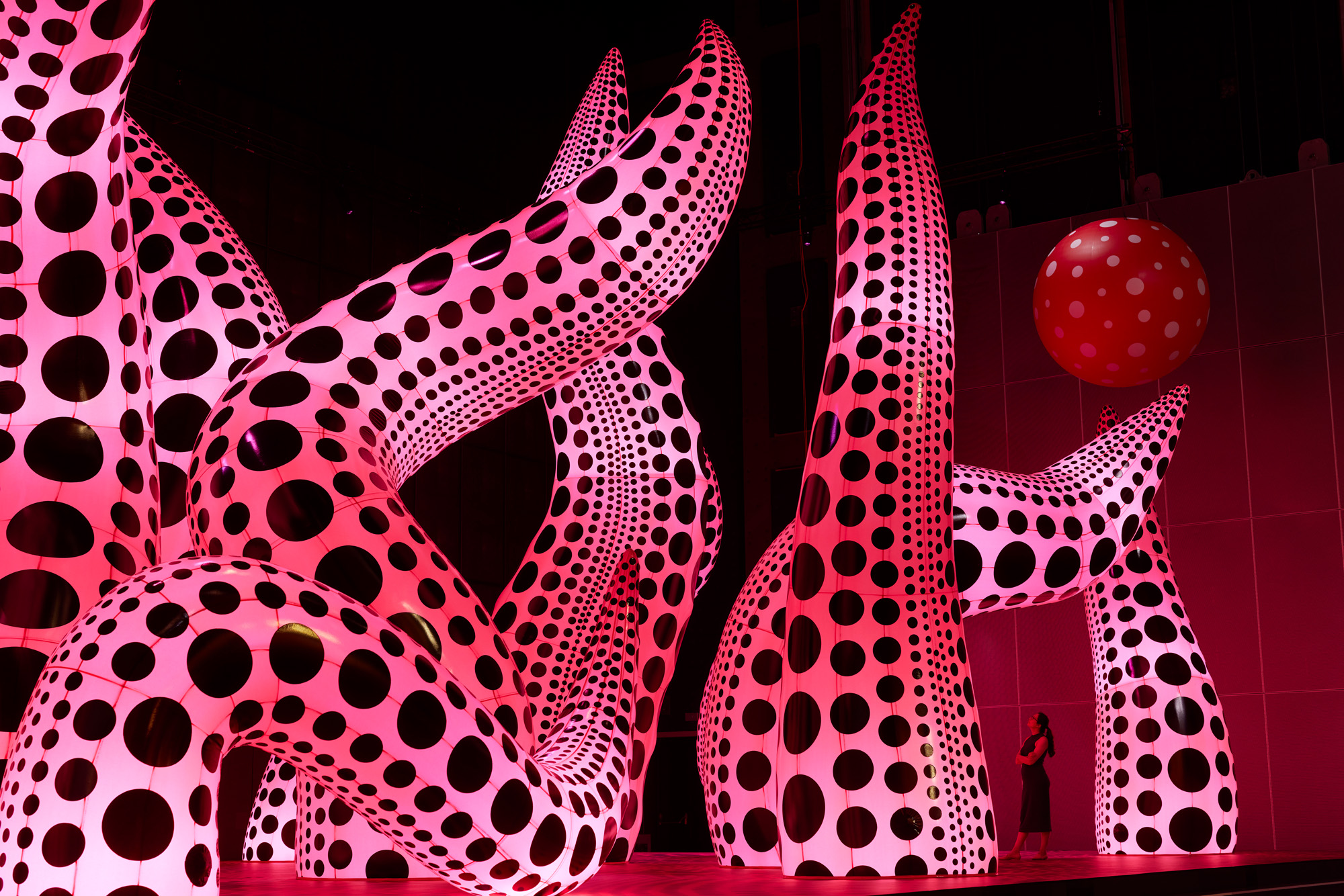

In summer 2023, she brought her largest-ever immersive experience to Manchester, where a new show celebrated three decades of her inflatable artworks, brought together for the first time. A vast warehouse space offered up a psychedelic, polka-dotted wonderland of dolls, pumpkins and tendrils.

Gallery director and cultural historian David Elliott, an early champion of her work, discusses her enduring vision as part of Kusama’s Wallpaper* October 2023 guest-editor takeover.

Yayoi Kusama: from those dots to infinity and beyond

Last Christmas, crowds flocked around the main display window of the Louis Vuitton flagship store in New York, where artist Yayoi Kusama stood 24/7 in animatronic facsimile, dressed in her signature polka dots in front of a large art installation of her work with Kusama-branded merchandise behind. In between overseeing large exhibitions of her work, such as last year’s ‘Yayoi Kusama: 1945 to Now’, her largest retrospective to date, at Hong Kong’s newly completed mega-museum M+, or her most ambitious artwork environment to date, ‘Yayoi Kusama: You, Me and the Balloons’, which showed this summer at Manchester’s Aviva Studios, she regularly adds to My Eternal Soul, a series of more than 900 acrylic paintings, started in 2009, a number of which hark back to the imagery of her earliest watercolours.

Raised in Matsumoto in a comfortable, middle class but fractured family, during a disastrous time of dictatorship and war, Kusama realised at an early age that ‘painting pictures seemed to be the only way to let me survive in this world and was rather like an outburst of my passion in desperation’. Her parents owned a plant nursery and seed farm and, from an early age, she started drawing pumpkins, inspired by the ones she saw at her family’s farm, giving form to her visions and hallucinations in which her body became absorbed into nature by being covered by patterns or dots. The evaporation of her identity in this way became both terrifying and awe-inspiring, reduced to a single molecule within an infinity of universes. Art for her became a way of making connections, not only to conjoin or heal her fragmented self, but also to embrace the world with kindness, humour, curiosity and wonder.

Feeling that Tokyo could not provide the freedom, stimulation or critical attention that her work needed, she moved, in 1957, first to Seattle, where she had been offered an exhibition, and then quickly to New York, where she set out to make an impact. In 1973, mental and physical health issues led her to return to Tokyo. Plagued by suicidal thoughts, as she had been on many occasions before, she checked herself into a psychiatric clinic, which, since 1977, has provided her with the security and space to work. Despite this, she has remained a far from remote figure, not only because her works reflect the terrors, conflicts and passions that drive her, and many of us, forward and are, in this sense, self-portraits, but also because she continues to project her personal image both as a part of her work and alongside it.

On arriving in New York, Kusama set out to establish the painterly language that had eluded her in Japan. Ocean and sea currents that she had observed at home and during her flight to America linked in her mind with impressions from childhood and watercolours of magnified cellular patterns she had already made. Out of this, the Infinity Nets evolved, her first large body of work, a fresh monochrome style of painting that did not look like anything else. Unimpressed by the frenetic splatters of the-then fashionable ‘action painters’, but attracted by artist Barnett Newman’s insistence on large scale, she embarked on a series of huge, obsessional paintings featuring repetitively rhythmical marks, loops and arcs in an implication of infinite breadth. Their production demanded sustained concentration, and their completion would often take 50-60 hours, uninterrupted by sleep. This exacted a severe toll on her health and, after a sequence of severe depressive episodes, she was hospitalised for anxiety and exhaustion in 1961.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Her first solo exhibitions in 1959 were a critical success; a new talent had obviously arrived. The all-over-surfaces, lack of obvious subject, and non-hierarchical, repetitive structure of her paintings also appealed to the young generation of New York artists known as minimalists who, in their creation of ‘non-specific objects’, were thinking of serial repetition not in terms of infinity but as emblems of post-industrial materialism.

At this time, in riposte to the rise of consumer culture in America, junk art and pop art had begun to take over the New York art world as Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg began to fetishise commercialism, trash and found objects in their work. Kusama started to produce her soft Accumulation sculptures, first exhibited in 1962, in which hundreds of sewn, stuffed, white-painted fabric ‘phallus-shaped protuberances’ were attached in chaotic assembly over domestic furniture, such as chairs, sofas and stools. The production of these demanded even more repetitive, obsessive work than the paintings, but their subject helped Kusama to ‘heal my feelings of disgust towards sex. Reproducing the objects was my way of conquering the fear …I was terrified of the phallus … I make a pile of soft sculpture penises and I lie down among them. That turns the frightening thing into something funny and amusing.’ The following year, she extended this idea into Aggregation: One Thousand Boats Show, her first immersive installation, in which a rowing boat, a symbol of transition between life and oblivion, covered in soft phallic forms, was surrounded by 999 screenprints that replicated its image in an infinite, hallucinatory expansion.

Kusama’s 1964 ‘Driving Image Show’ (subtitled ‘Sex obsession. Food obsession. Compulsion-furniture, Repetitive-room, Macaroni-vision’) featured writhing, crammed-together phallic accumulation sculptures set in a quasi-domestic environment, the walls of which were hung with net paintings. This space was occupied by female mannequins covered in dry macaroni that was also splurged across the floor. This, she explained, was ‘not only part of…personal trauma, but a response to the uniform environment of America – strangely mechanised and standardised: nausea-inducing visions of repetitiveness; endless highways, endless conveyor belts’.

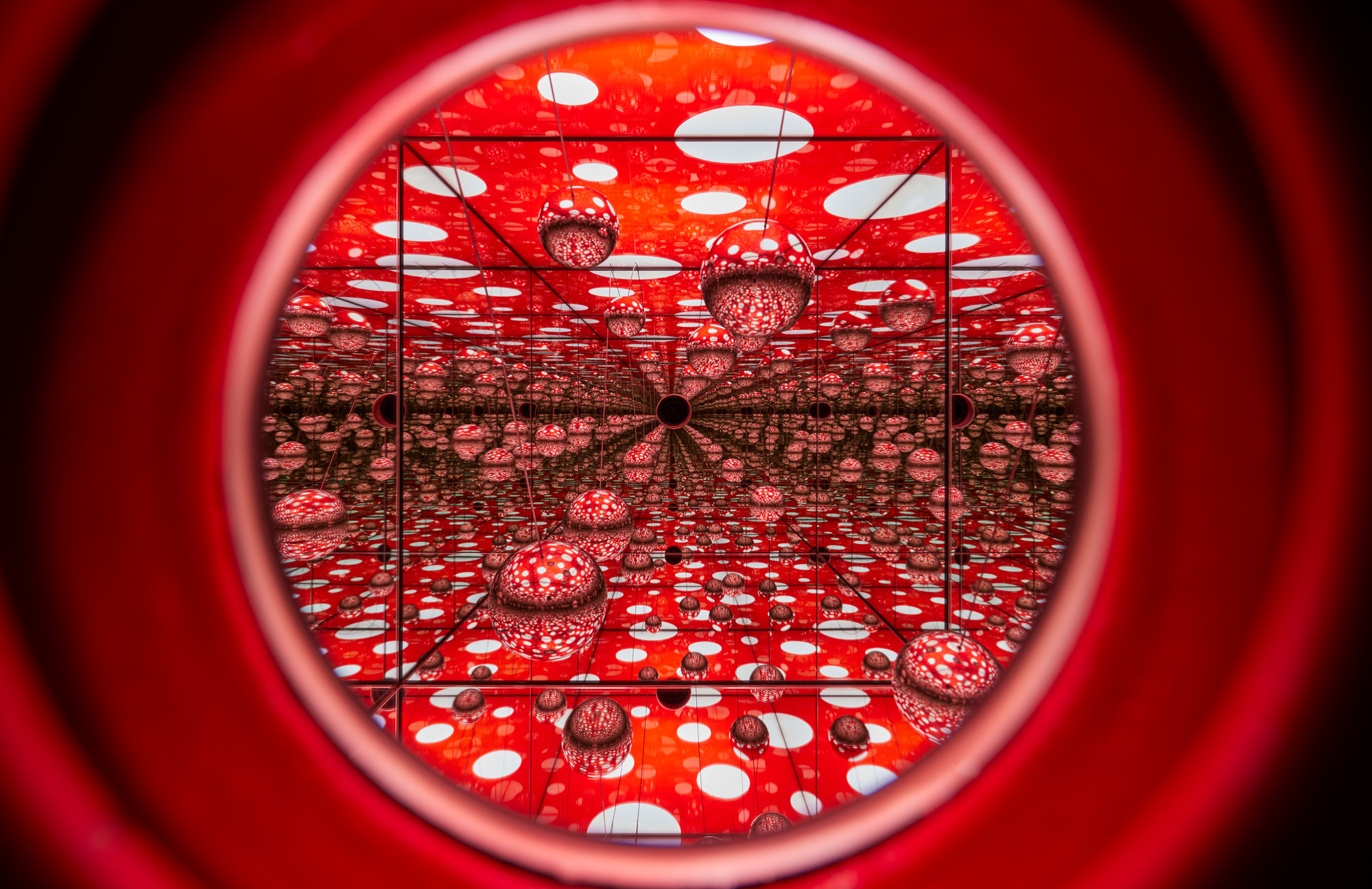

The following year, showing an equally strong sense of self-aware humour, and throwing an actively critical eye on what she regarded as rampant nationalism and segregation within American society, she produced Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field, the first in a continuing series of Infinity Mirror Rooms, in which visitors could share her experience by entering a mirror-lined space to be presented by myriad reflections of themselves and its contents – in this case, there were also thousands of stuffed white phalli, covered in red polka dots, sprouting up from the floor that, for Kusama, ‘exorcised sexual sickness’.

The idea of diminution of self by infinite replication in miniature that the Infinity Mirror Rooms induced took a different turn in 1967 when, against the background of the Summer of Love in San Francisco and the hippy movement worldwide, Kusama directed and participated in a series of performances entitled Self-Obliteration: An Audio-Visual Light Performance, in which she painted fluorescent polka dots on to performers; the polka dot expressed equality and connection between humanity, nature and the universe. This action soon proliferated when, with a team of nude dancers, she travelled across New York parks, museums and memorials, obliterating the destructive egos of themselves, and others, with polka dots, in direct protest against the war in Vietnam and in support of civil and gay rights. The social and political implications of Kusama’s art soon became news, and many people became outraged.

In Open Letter to My Hero Richard Nixon, she declared ‘Our earth is like one little polka dot, among millions of other celestial bodies, one orb full of hatred and strife amid the peaceful, silent spheres. Let’s you and I change all that and make this world a new Garden of Eden. Let’s forget ourselves, dearest Richard, and become one with the Absolute, all together in the altogether. As we soar through the heavens, we’ll paint each other with polka dots, lose our egos in timeless eternity, and finally discover the naked truth. You can’t eradicate violence by using more violence.’ But answer came there none.

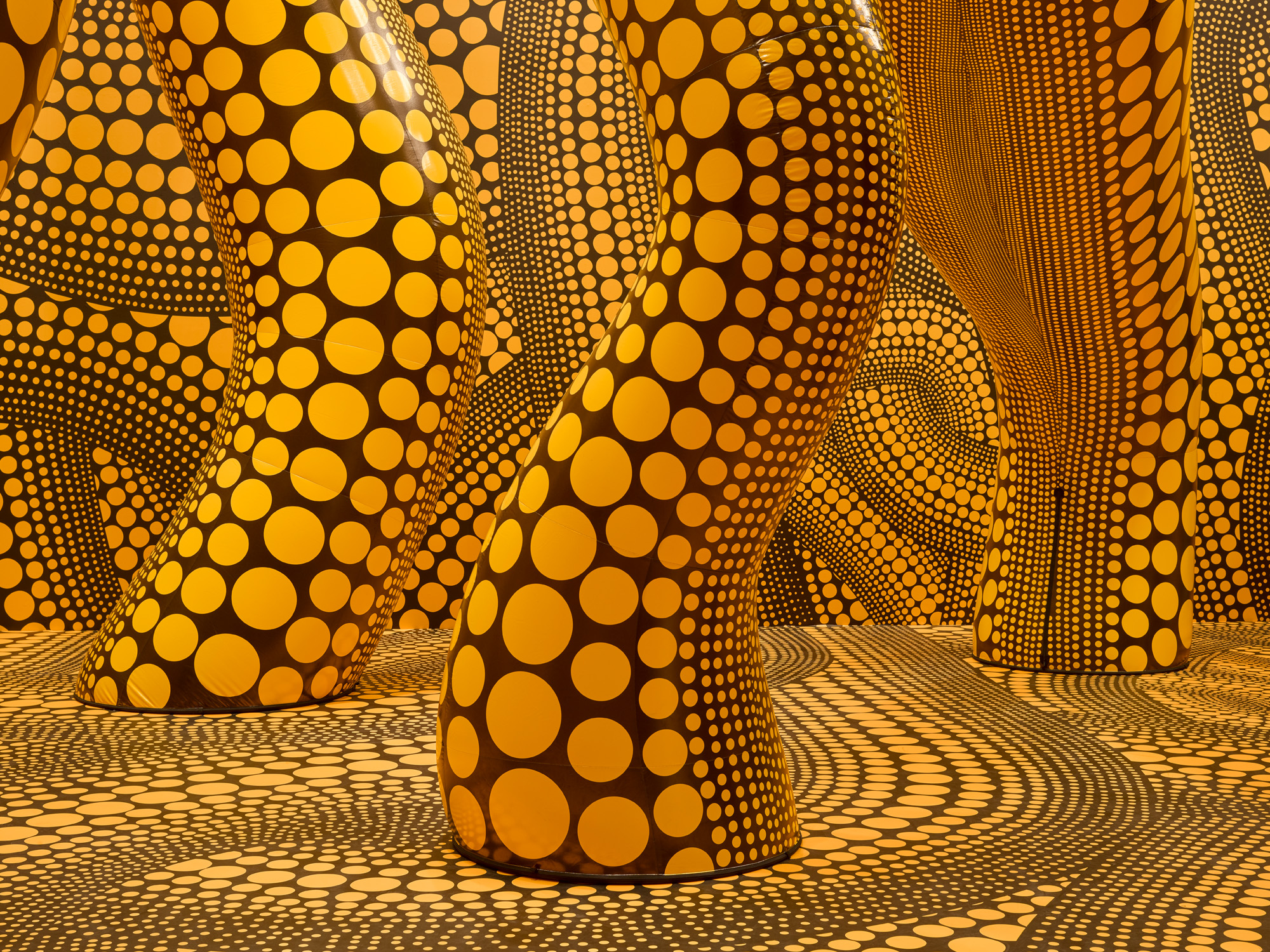

Kusama’s first inflatable works date from the mid-1990s, and their flexibility, lack of bulk and relative ease of transport have enabled her to think on a previously unimagined scale. In this respect, the voluminous spaces of Manchester’s Aviva Studios provided a perfect receptacle and, when encompassed within this environment and faced by the size of the works, we become like the characters in Alice in Wonderland or the inhabitants of Lilliput as we encounter the wide span of Kusama’s whole imagination. This feeling is not uncomfortable because as we become entangled in infinity nets, obliterated by dots, peer into an infinity globe, overseen by fluorescent mobile balloons, or experience a video performance, there is still space to contemplate, and even to sleep. The artist herself is ever present: as Yayoi-chan, a 12m-tall young girl back in Matsumoto with her dog, gazing at her repeated image in a supersized mirror; as a ‘solid and chubby’, 10m-wide spotted pumpkin with which she jovially identifies; and in a video, her face projected above our heads as she sings in Japanese the mournful Song of a Manhattan Suicide Addict (2007). In this lament of memory, pain, sadness and intransigence in the face of adversity, cuteness evaporates, but stillness remains. We are offered a gift we can all share, along with her energy and solace.

The October 2023 issue of Wallpaper* is available in print from 7 September, on the Wallpaper* app on Apple iOS, and to subscribers of Apple News +. Subscribe to Wallpaper* today

Curator, writer and museum director David Elliott has lived and worked in in UK, Sweden, Japan, Turkey, Germany, Australia, Ukraine, Russia, Serbia, and China. He has taught in a number of universities and art schools and

published widely about modern and contemporary art; his most recent book Art & Trousers. Tradition and Modernity in Contemporary Asian Art, a collection of new and previous essays, was published by the Art Asia Pacific Foundation and Singapore UP at the end of 2021.