Kader Attia’s breakthrough work, Ghost (2007), began as a cast of his mother. Childhood memories of seeing her in prayer, among dozens of devout Muslim women, prompted the artist to wrap her in layers of aluminium foil as she knelt, creating a life-size figure with the characteristically shiny material. He then repeated the process until he had a crowd of 40 figures, with minor variations in posture and arranged neatly in a grid to form an installation (subsequent iterations have involved more figures cast from different people). Viewers approach the figures from behind, mimicking the perspective from which Attia would have encountered the long and narrow spaces that often served as mosques in the Paris of his childhood. Only when they reach the other end of the exhibition space do they realise that the figures are empty shells; their burka-like hoods each conceal not a face but rather a haunting void.

Despite its beginnings as a personal gesture of filial love, Ghost is mostly about wider, weightier ideas, among them the perception of religion, the search for a sense of belonging, and the promises and pitfalls of multiculturalism. These complex themes have long fascinated Attia: his first sculpture, titled The Dream Machine (2003), showed a hooded figure staring at a vending machine stocked with purportedly halal versions of items that are either forbidden in the Islamic faith, or intertwined with ideas of modernity: pork products, alcohol, an American passport, a visa card. Conceived in the aftermath of 9/11, ‘it was an ironic way of showing how racialised communities also mirror what the dominant society is producing and consuming,’ recalls Attia, reached in his Berlin studio via video call.

The Dream Machine took on colonialism and its modern manifestations: ‘There’s this idea that non-white [populations] have to become white inside, all the while staying the basis of society, the slaves of capitalism,’ adds Attia. He considers the work to be an early form of a critique he can make about today’s gig economy: ‘The owners of Uber say their drivers are not employees, but rather their own CEOs. And I think this sort of neoliberal rhetoric is very dangerous, because it shows that colonisation continues. The extraction of values from the racialised body continues.’

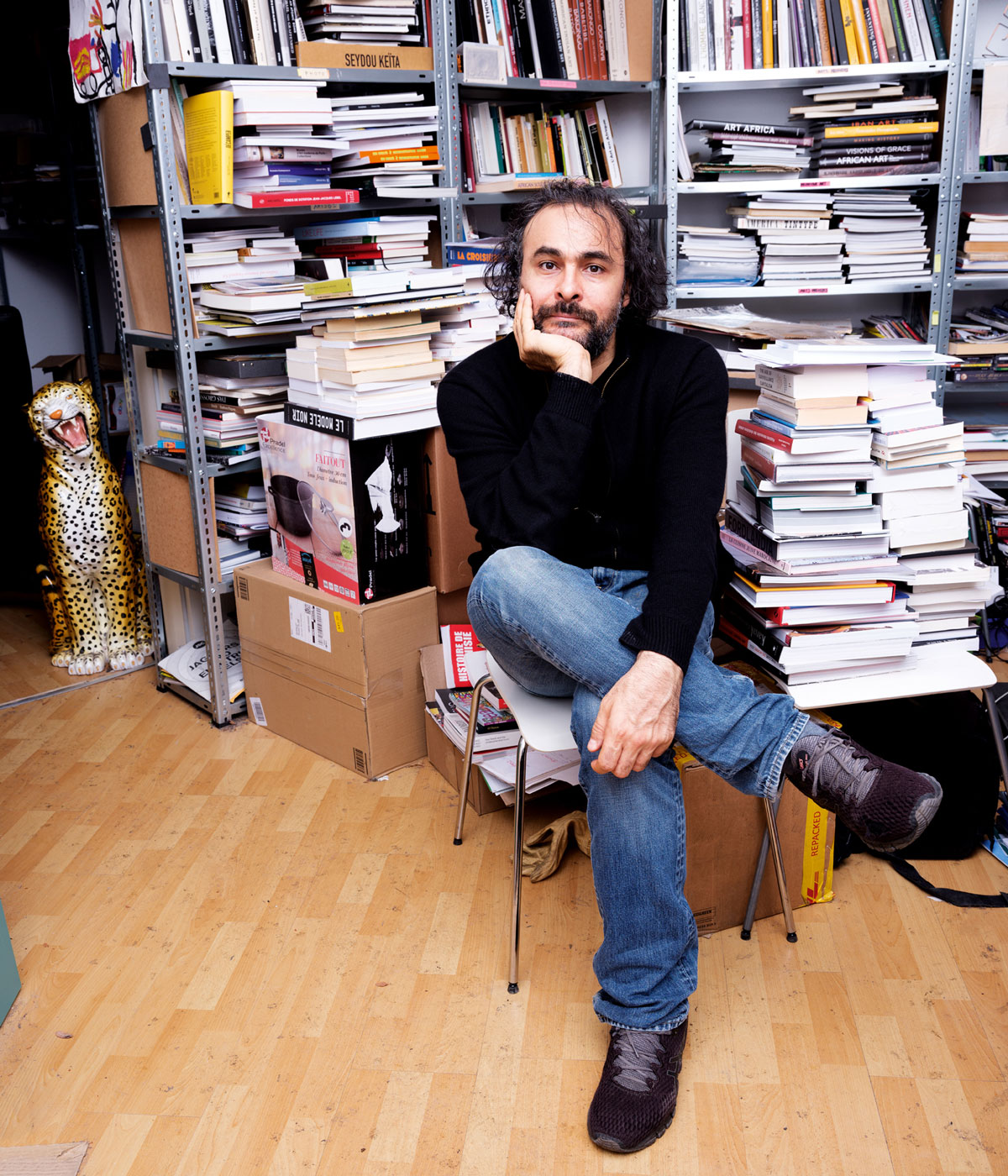

Artist Kader Attia photographed in his Berlin studio for the May 2021 issue of Wallpaper*.

Born in 1970, Attia grew up between a Paris banlieue and Algeria, a former French colony and the country of his ancestors, while, by his own admission, struggling to figure out where he belonged. ‘My father used to tell me that as a migrant, the most important thing is neither the kind of place where you live, nor the one you’re going to find. The most important thing is the journey,’ he says.

His multifaceted upbringing inspired a yearning for travel: in his twenties, to fulfil his national service requirement, he worked for three years at an NGO in Congo. During this time he put on his first exhibition, a series of photographs that documented a journey along the Congo River on a massive passenger boat that he likens to a floating city. ‘It was one boat with 1,000 people and then attached to this boat, probably five other boats without motors, each with 1,000 people living on them.’ He was the only foreigner apart from two missionaries who were translating the Bible into Pygmy, and among the passengers was a man who had three live crocodiles, their mouths tied with raffia, who explained that he would sell them in order to afford to stay for a few days at his next stop. The journey took Attia to the most remote places he’s visited, and impressed on him the shock that capitalism brought to these parts of the world.

‘What drives me to travel is not only the need to find the traces of what I’ve read in books,’ Attia says, gesturing to the fully-stacked library behind him, ‘but also the reaction of these locations to the contemporary global order. I’m not into the idea of the journey as a sort of ethnologist or anthropologist, but rather, as a philosopher or artist. Cultures always counteract a hegemony, particularly when the hegemony comes from another culture which is occupying it, a Western one.’

La grand miroir du monde (2017), a sculptural carpet made of fragmented mirrors that invites the viewer to think about individual and collective perceptions of the world and their positions within it in the postcolonial era

Attia’s next project explored the fringes of modernity in a different way: back in Paris, he stumbled upon a café that was frequented by transgender Algerians, many of them illegal immigrants who had recently fled civil war in Algeria and were now doing sex work to make ends meet. He befriended them, awed by their courage to live authentically in a world where their gender and migrant identities made them doubly alien: ‘For me, they were really the incarnation of total bravery.’ These friendships resulted in the photo series The Landing Strip (2000-02), showing moments of happiness amid hardship. Attia wanted to disprove the notion that the lives of marginalised people are consistently miserable: ‘It’s not true. There are moments when we need to laugh, we need to drink, we need to party.’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

With its defiant joy, The Landing Strip gives a voice to dispossessed groups that have often been forced to hide in silence. Attia continued this work in the 2011 video piece Collages, travelling to Mumbai with the journalist and transgender activist Hélène Hazera to visit communities of hijras, who identify as third gender and often struggle to fit into Indian society (their exclusion is in part a legacy of British colonial law, which categorised them as criminals and deviants).

He is interested in the ills of Western civilisation and the lingering effects of colonialism, but equally, how non-Western cultures have resisted. He mentions his grandmother’s involvement in the Algerian War of Independence, collecting jewellery which she melted down and sold to support resistance efforts. Much of this jewellery had been made from old coins, bearing the countenance of colonial rulers. Similarly, while travelling in Asia two years ago, he came across women’s hair jewellery forged from the coinage of French Indochina. He sees these modest objects as small counter-reactions to colonial history: ‘Silent resistance which works through craft productions is, for me, the first sign of reappropriation, which will one day become a revolution,’ he contends.

This month, the rich and varied strands of Attia’s work have come together in a major solo exhibition at the Mathaf Arab Museum of Modern Art in Doha, curated by its former director Abdellah Karroum. Titled ‘On Silence’, the exhibition highlights the stifling effects of postcolonial trauma and the need for psychiatric ‘repair’. It is at once global in scope, including works such as Ghost and collages from the Hijras series, and conceived specifically for the Middle East, which Attia considers ‘one of the most hindered regions in the world today’. ‘I’m thinking about the last 20 years, the way the Americans have completely destroyed Iraq, the way Israel is with Palestine, the way Saudi Arabia is driving a colonial war in Yemen. There’s an unbelievable continuity of colonialism today.’

In his view, silence, or an unwillingness to confront tumultuous histories and correct injustices, has normalised colonial domination, and ‘On Silence’ is a valiant effort to criticise today’s perpetrators as well as awaken the silent enablers.

Crucial to the show are two new installations. The eponymous On Silence comprises a roomful of prosthetic limbs, suspended from the ceiling to occupy the visual field of the viewer. Attia was keen to avoid pieces that ‘looked like they belonged in a collection of contemporary art’, and deliberately sought out prosthetics that bear traces of their former owners. ‘I want something that really speaks by its own texture and patina of a used object, that whispers of political violence,’ he explains. Many were sourced from Syrian refugees, but the intent of the piece is broader: ‘Prosthetics refer most of the time to mine bombings, to war in [places like] Angola, Vietnam and Palestine, everywhere where colonial domination happened. You have dead people, and the survivors are the ones who are amputees. And you can be amputees both ways, physically, but also traumatically. Most of the time, they’re both.’

The Object’s Interlacing, 2020, includes a projection showing interviews from people around the world giving their opinions on the legacy of traditional art today. Facing the screen are replicas of ethnographic objects, their shadows reflecting on the interviewees

The other new installation, The Object’s Interlacing, takes on the cultural legacy of colonialism, specifically how former colonial empires have taken art from other parts of the world that they ravaged. Attia has long been interested in the question of restitution (a 2013 work, Dispossession, scrutinised the origins of the Vatican’s ethnological collection). Here, he’s created an hour-long video piece that stitches together interviews with key players in the debate: historians, anthropologists, politicians, psychoanalysts, offering different points of view. Serge Guézo, a direct descendant of King Gezo of Dahomey and now an activist for the preservation of cultural heritage in Benin, features in the film, as does the great-grandnephew of the French general who sacked Gezo’s palace (in 2018, President Emmanuel Macron pledged that France would return the looted artworks to Benin).

Attia’s objective is not to advance a particular agenda, but rather to highlight the cultural and economic significance of artefacts, and the complexity of untangling their histories. Opposite the video projection are 27 copied African artefacts – some of them made in Senegal by contemporary craftspeople, others 3D-printed in Germany – anthropomorphic and appearing to watch the film alongside the show’s visitors, reinforcing the idea that history has its eyes on today’s decision-makers.

Given Kader Attia’s choice of subjects and the weight of his ambitions, it is easy to imagine him as a tortured soul, frustrated by our collective inability to heal the wounds of our troubled past. But he calls himself an optimist, crediting a love of art and philosophy for his faith in human virtue. ‘I’m not optimistically naive,’ he qualifies, ‘If we need to struggle against very complex, powerful forms of repression or dominance, we need relevant artworks, and relevant discourse.’

In 2016, the desire to promote discourse led him to join forces with restaurateur Zico Selloum to create La Colonie, ‘a laboratory of life’ in Paris that offered workshops, exhibitions and other events around big cultural issues. While the venue was forced to close last year because of the pandemic, Attia recently organised a new series of pop-up workshops called Fragments of Repair/La Colonie Nomade, taking place at the La Dynamo de Banlieues Bleues concert hall in Pantin, alongside an online series of lectures, conversations, and assembly forums. He concludes, ‘it’s very important to listen to the other: other cultures, other contexts, other economies’ – so they will be silent no more.

The view of Attia’s Ghost, 2007 as visitors first enter the exhibition; only when they reach the other end of the space do they realise that the aluminium figures are empty shells, their burka-like hoods each conceal not a face but rather a haunting void

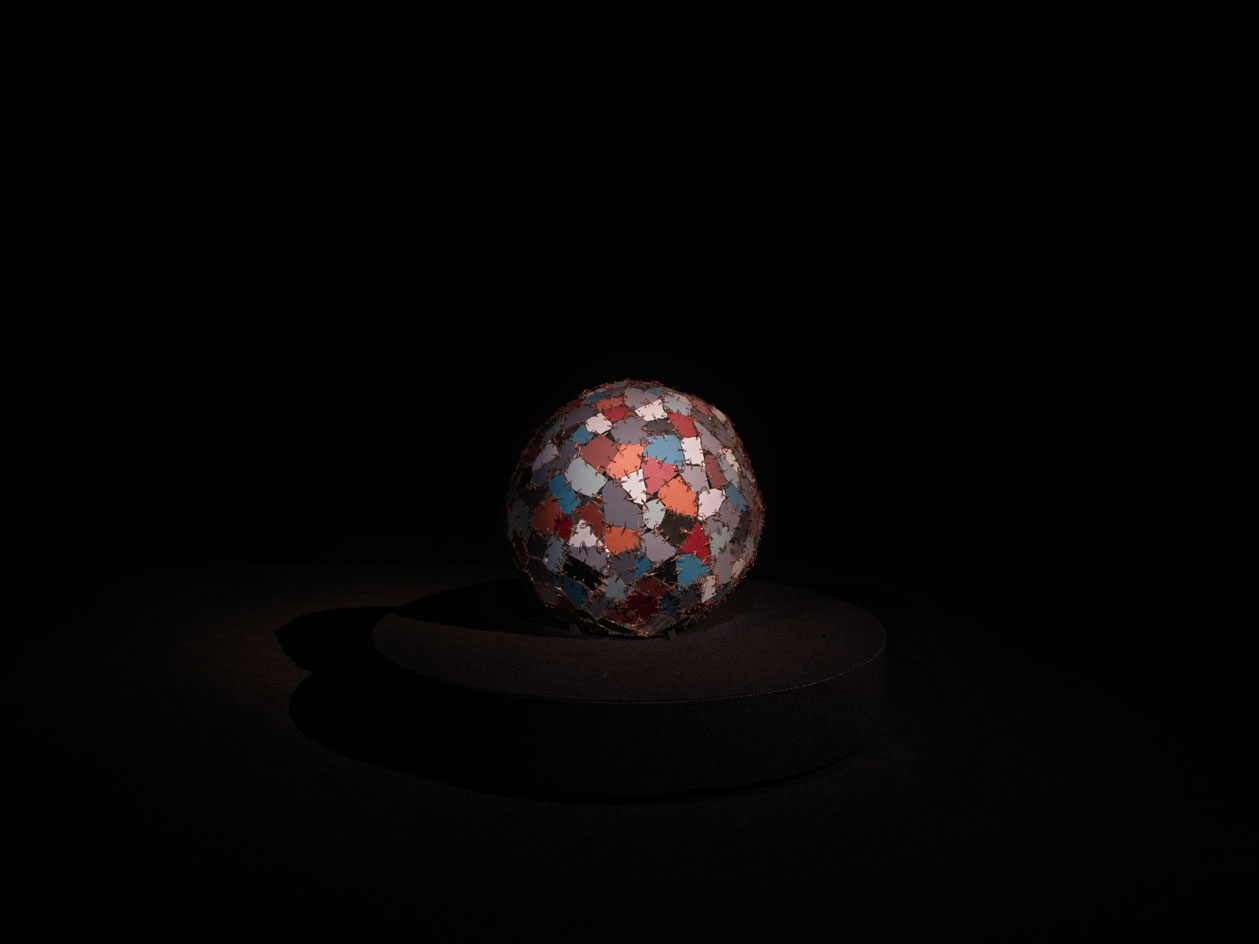

Chao + Repair = Universe, 2014, made of mirror fragments tied with metal wire into a roughly spherical form, suggests hope for healing

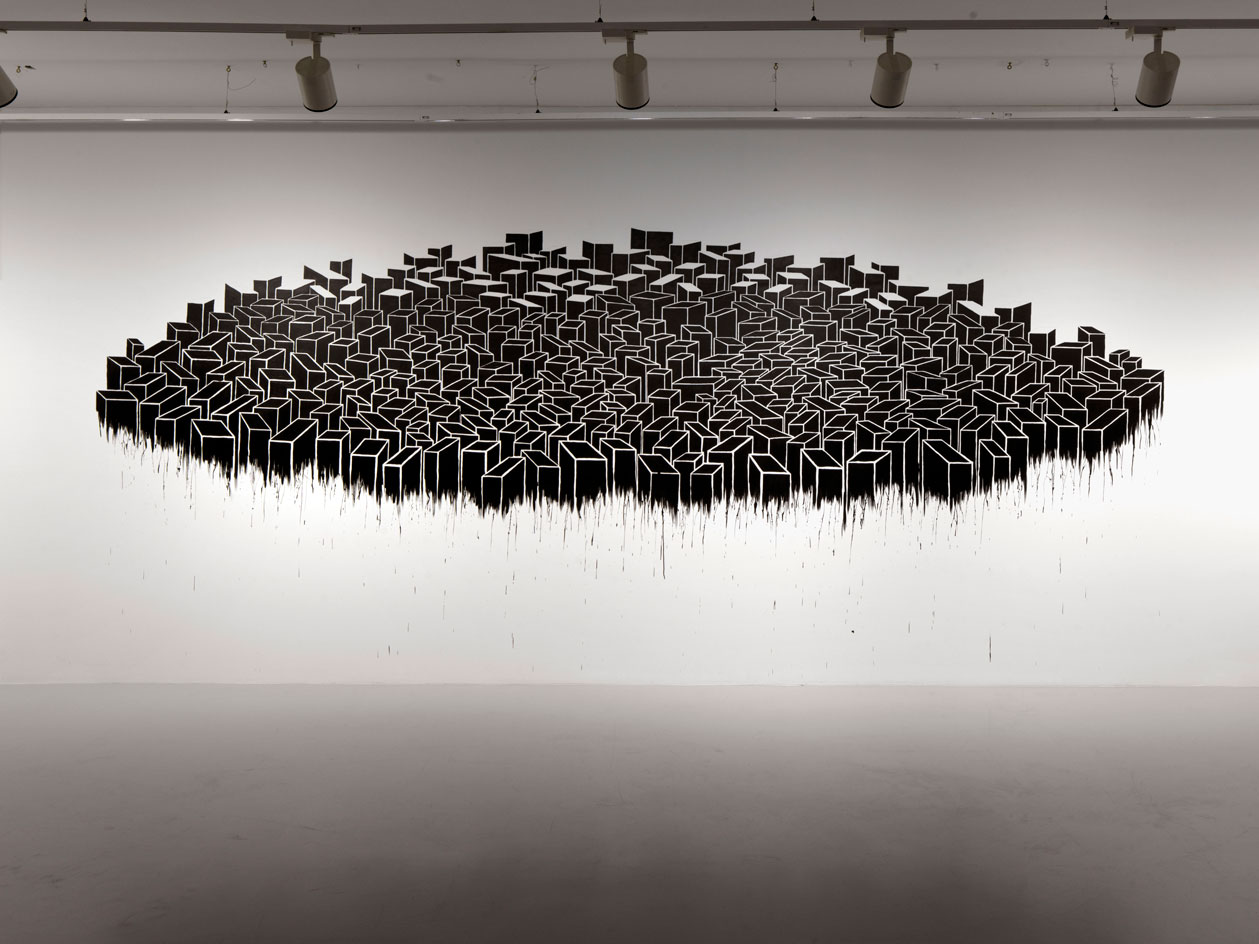

Oil and Sugar #2, 2007, in which the gradual collapse of sugar cubes doused in black oil embodies the crises and contradictions that can emerge within all cultural systems

From Attia’s Separated together series, traditional terracotta tiles, cracked and repaired with metallic stapes

An artwork from Attia’s Untitled (Repaired Broken Mirror) series, comprising broken mirrors stitched back together with copper wire

The Repair from Occident to Extra-Occidental Cultures, 2012, resembling an immense archive or museum storeroom, and exploring different attitudes towards repair found in Western and non-Western cultures

INFORMATION

‘On Silence’ is at Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha, Qatar, until 31 March 2022

This feature was first published in the May 2021 issue (W*265). Subscribe to Wallpaper*

TF Chan is a former editor of Wallpaper* (2020-23), where he was responsible for the monthly print magazine, planning, commissioning, editing and writing long-lead content across all pillars. He also played a leading role in multi-channel editorial franchises, such as Wallpaper’s annual Design Awards, Guest Editor takeovers and Next Generation series. He aims to create world-class, visually-driven content while championing diversity, international representation and social impact. TF joined Wallpaper* as an intern in January 2013, and served as its commissioning editor from 2017-20, winning a 30 under 30 New Talent Award from the Professional Publishers’ Association. Born and raised in Hong Kong, he holds an undergraduate degree in history from Princeton University.