Modern masters: the ultimate guide to Jean-Michel Basquiat

New York artist Jean-Michel Basquiat centred the Black subject in political, electric works which resist easy definition

Jean-Michel Basquiat emerged in downtown New York at the turn of the 1980s, when the city was broke, public services shuttered, and a new generation of musicians, filmmakers, and artists were reinventing culture in derelict lofts. Born in Brooklyn in 1960 to a Haitian father and Puerto Rican mother, he grew up between museum trips with his mother and the fractured rhythms of downtown life. By his early twenties he was exhibiting internationally, hailed as a prodigy of a new, unruly painting. His canvases bore little resemblance to the polite post-minimalism still hanging uptown: literate, urgent, full of anatomy diagrams and music references, a mixture of self-portraiture and social commentary that seemed to belong as much to a subway wall as a museum.

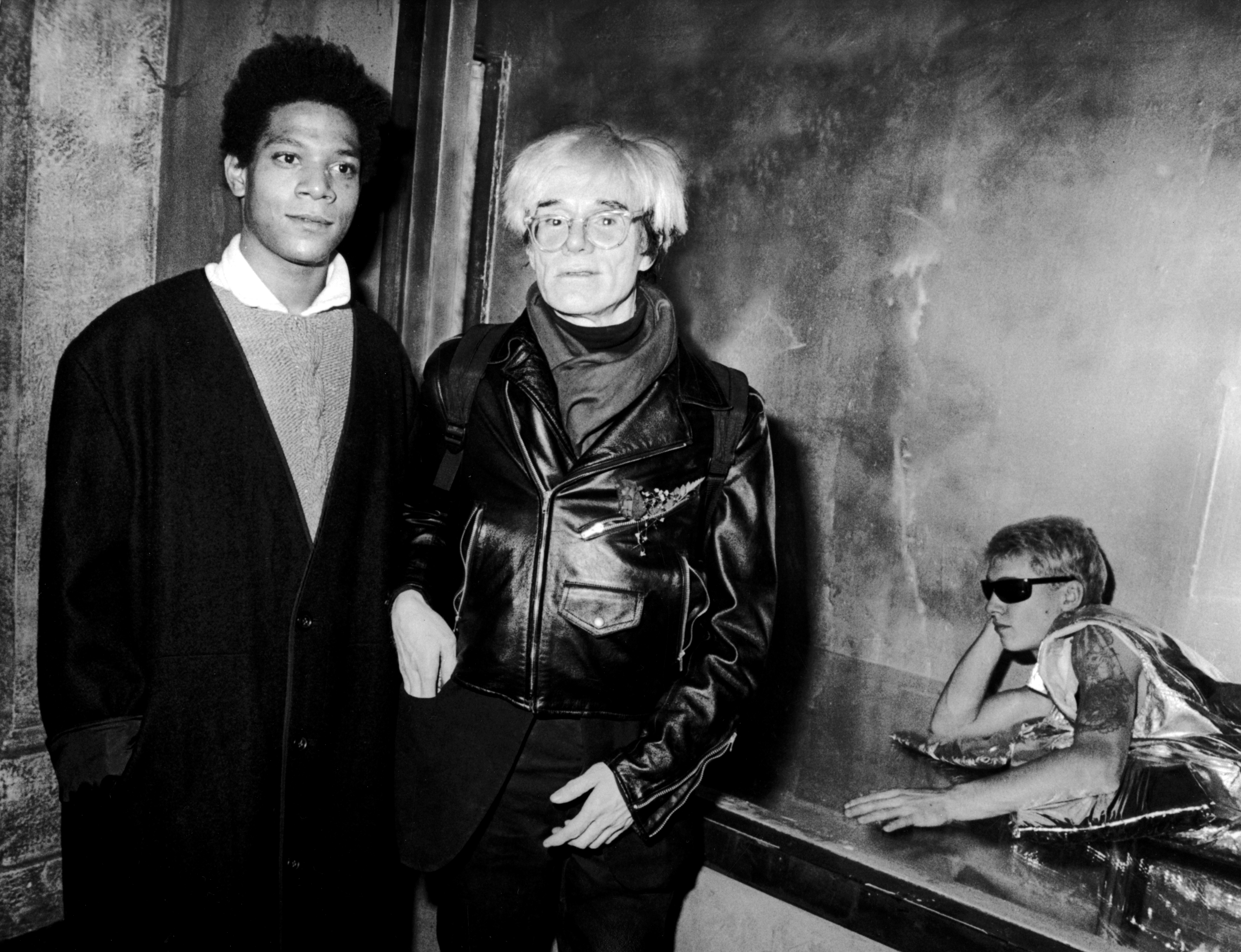

New York City, November 7: Jean-Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol attend Gifts For The City Of New York; Benefit for Brooklyn Academy of Music on November 7, 1984 at Area Nightclub in New York City.

Style

Basquiat redefined who and what counted as 'serious' painting, insisting that Black subjects and histories occupy spaces long denied them. He layered bebop, boxing, colonial history, and medical textbooks onto doors, panels, and canvases, producing works that felt improvisational but were quietly exacting – a controlled chaos only he could summon. The drips, cross-outs, and abrupt juxtapositions were not accidents but a refusal to smooth the dissonance of his sources, reflecting the fractured politics of the Reagan era: rising policing, rolled-back social programmes, and culture wars that made the downtown art scene both exhilarating and precarious. In a decade dominated by glossy neo-expressionism and Wall Street swagger, Basquiat’s paintings held onto the raw textures of life outside collectors’ lofts.

More than thirty years on, Basquiat’s paintings remain electric, not as 80s relics but because the injustices and contradictions they expose – racism, inequality, commodification – are still with us. Yet the paintings are more than political statements. They are hybrid objects: Haitian and Puerto Rican folklore sits alongside Leonardo da Vinci sketches; graffiti syntax collides with the scale and structure of Renaissance altarpieces. They display the restless intelligence of someone sampling and remixing long before those ideas became art-world buzzwords, conscious of being read, misread, and commodified even while creating.

Installation view of ‘Basquiat x Warhol. Painting 4 Hands’ at Fondation Louis Vuitton

Early life

Encouraged to draw from an early age, Basquiat spent part of his childhood in hospital after a car accident, poring over Gray’s Anatomy. As a teenager he drifted in and out of school, sold painted postcards, and with fellow New York-born artist Al Diaz, scrawled cryptic SAMO© slogans across downtown walls. By 1981 he appeared in PS1’s New York/New Wave exhibition; a year later he had his first solo show. Collaborations with Andy Warhol brought both visibility and suspicion – their joint canvases pitched Pop’s logos against Basquiat’s furious mark-making – while magazine covers further enhanced his burgeoning celebrity status. Behind the acclaim lay the strain of being a young Black painter in a predominantly white system. In August 1988 he died of a heroin overdose, aged 27, leaving hundreds of paintings and thousands of drawings.

Jean-Michel Basquiat outside the Mary Boone Gallery on West Broadway, March 9, 1985

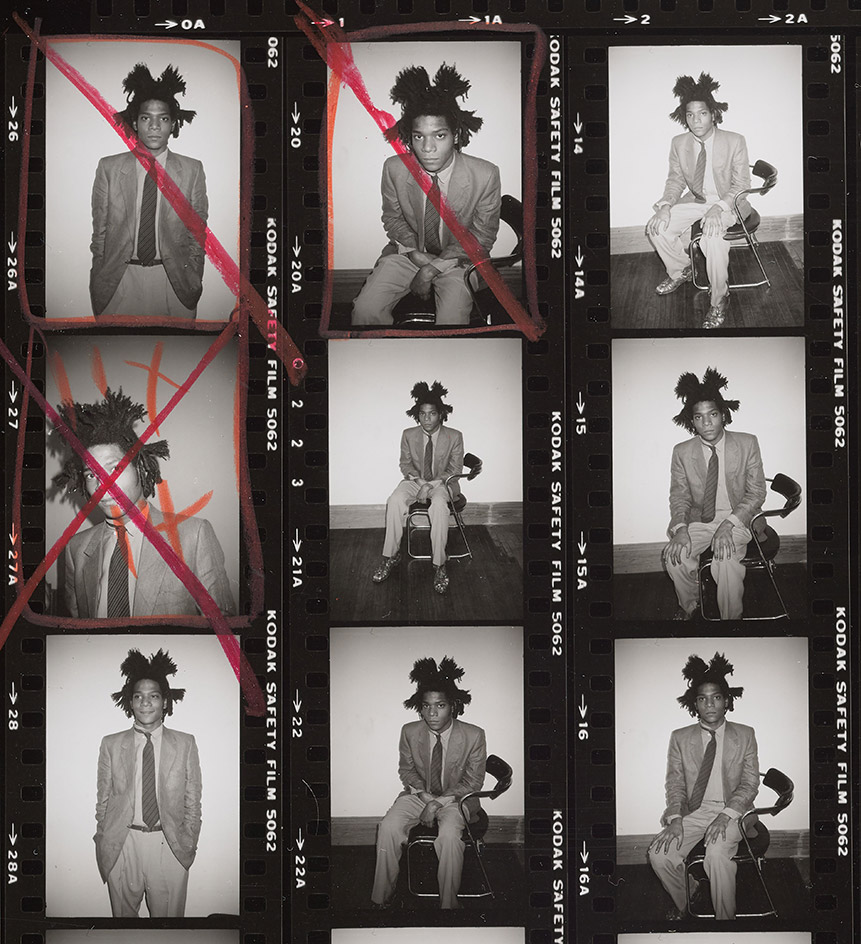

Jean-Michel Basquiat photo shoot for Polaroid portrait by Andy Warhol

Themes

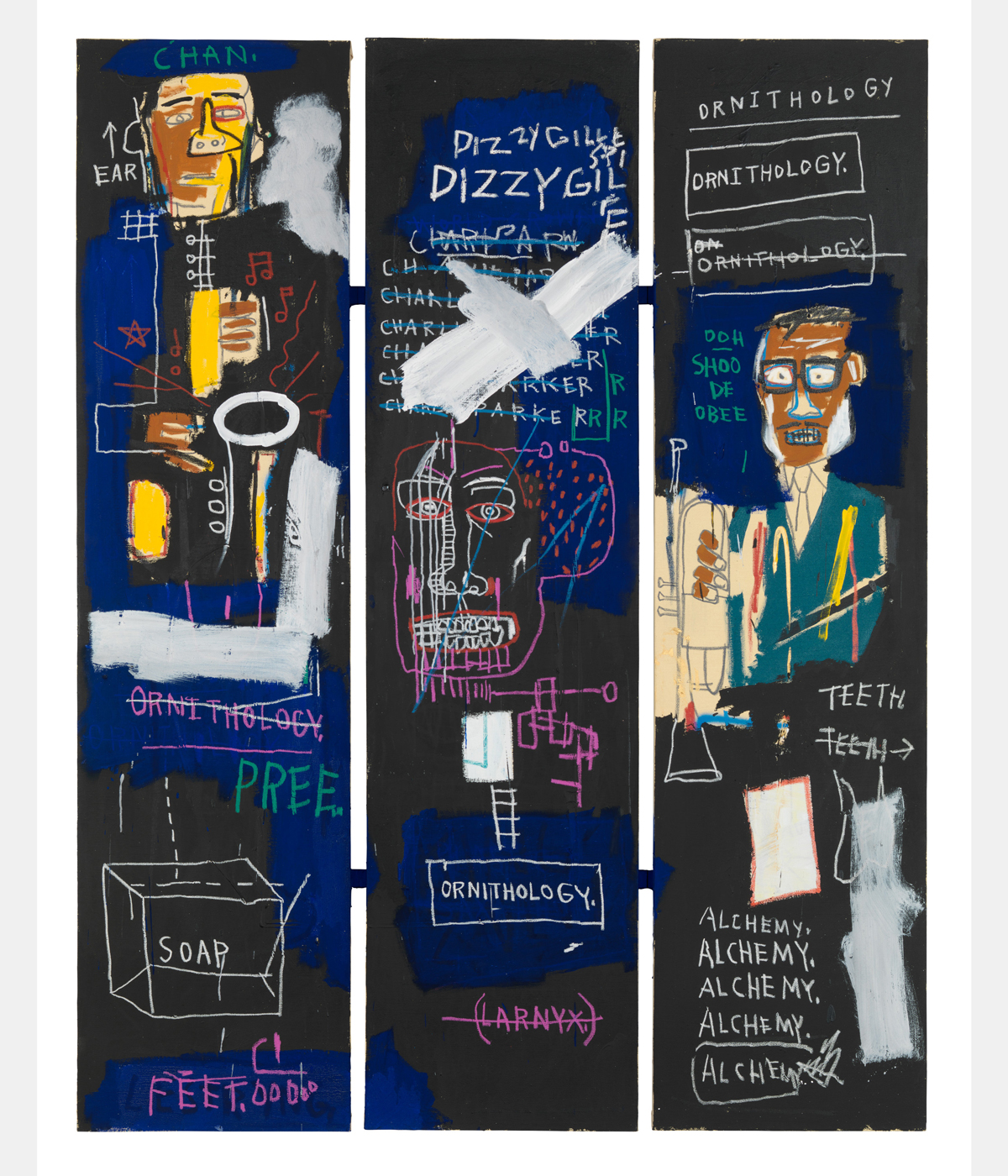

Recurring themes unify his work. Anatomy was a means of probing what lies beneath the surface. He honoured Black heroes – Charlie Parker, Joe Louis – by placing them at the centre of high art, a corrective to decades of erasure. He explored anatomy and mortality not as gothic flourish but as a way of looking under the skin, of seeing structures of power as well as of flesh. His canvases teem with language: names of commodities, of saints, of the enslaved; words struck through or overwritten as if to stage the violence of erasure itself. And he turned his own predicament – outsider and insider, celebrated and caricatured – into subject matter, producing works that are at once self-portrait and cultural diagnosis.

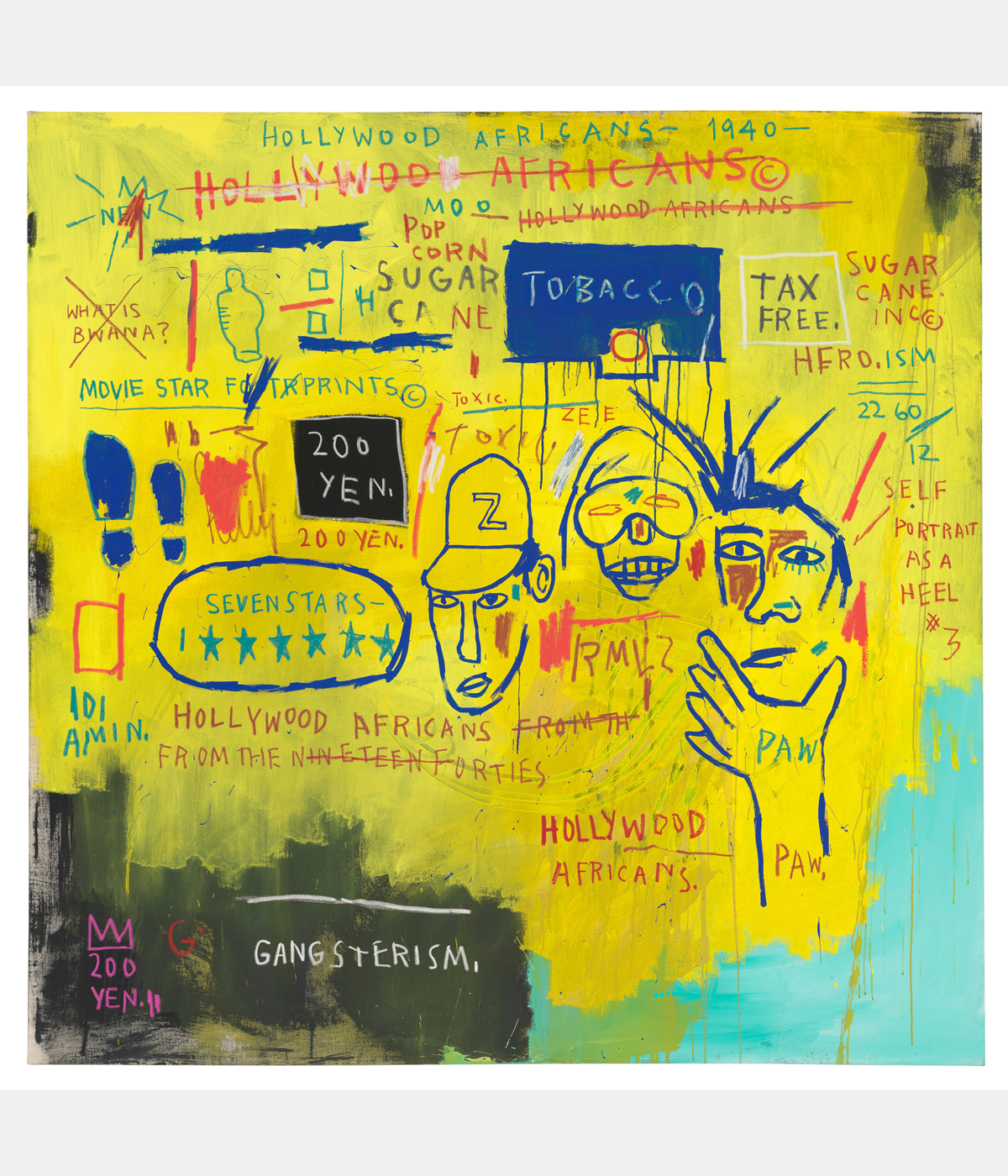

Jean-Michel Basquiat Hollywood Africans, 1983

Works

Untitled (1981 Skull), one of his first big statements on identity, fills the canvas with a head that is mask, portrait and anatomical diagram at once. Painted in searing reds and blues, its split face – half flesh, half bone –reflects both his fascination with what lies beneath appearances and the exposure of being a young Black artist under scrutiny.

Boy and Dog in a Johnnypump (1982) anchors street memories in high-art scale. The “Johnnypump” is New York slang for a fire hydrant opened in summer, a tiny, almost affectionate detail in a painting otherwise full of sharp teeth and wiry limbs. The boy and dog, cartoonish yet threatening, evoke both the joy and menace of the city; the blazing palette nods to Matisse even as the line stays spiky and uncontainable.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Irony of Negro Policeman (1981) distils a complex critique of institutional power. A boxed-in, helmeted officer appears as diagram rather than person, the angular helmet evoking both riot gear and medieval armour. The title’s bluntness forces the viewer to confront a stereotype and its contradictions, turning a commonplace image into a lesson in complicity.

From left, René Ricard, Gold Griot and Flexible

Defacement (The Death of Michael Stewart) (1983), painted after the killing of a young graffiti artist in police custody, compresses rage and grief into a small, intense composition. Cartoonish figures with clubs, hastily scrawled names and a bright, almost sickly palette make it feel like a visual shout rather than a gallery piece – a furious elegy cut from the wall of Keith Haring’s studio.

What unites these works is not style alone but a way of thinking on the surface: painting as a site where cultural memory, personal experience and political crisis converge. At a time when much of the art world smoothed itself into a marketable product, Basquiat left contradictions visible. Far from the myth of a street kid turned star, he was a historically literate painter who bent the languages of Western art to tell a different story, leaving an unflinching record of a city – and a country – in transformation.

Horn Players

Untitled (Boxer), 1982

Untitled (Tenant), 1982

Finn Blythe is a London-based journalist and filmmaker