Modern masters: the ultimate guide to Yayoi Kusama

Throughout her career, Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama has created an entirely new genre of hallucinatory, immersive and playful art.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Long before she became synonymous with mirrored rooms and spotted pumpkins, Yayoi Kusama was a child in rural Japan, staring at a field of flowers that multiplied until they seemed to swallow her whole. Born in Matsumoto in 1929 to a conservative, landowning family, she reported seeing patterns consume walls, floors, and even her own body. Drawing and painting became a survival mechanism, though her mother often tore up her sketches, dismissing them as shameful.

Rather than fading, these visions sharpened into an obsession with repetition and obliteration. Endlessly dotting, multiplying, or mirroring forms was a way to master what threatened to overwhelm her and dissolve the self into something larger. What began as defence became the engine of her practice: repetition as both compulsion and liberation, obliteration as both erasure of trauma and creation of new worlds. This logic underpins everything from her Infinity Net paintings to the mirrored rooms, where viewers are drawn into the same disorienting cycle – trapped yet liberated, overwhelmed yet absorbed – that Kusama herself endured.

Yayoi Kusama next to her Dot Car, 1965

Yayoi Kusama's early career

When she arrived in New York in 1958, Kusama was fleeing Japan’s rigid social conventions and insular art scene. Trained in the highly codified traditional nihonga painting technique, she found the constraints suffocating, particularly as a young woman producing obsessive, unsettling work. Encouraged by correspondence with Georgia O’Keeffe, she sought the city as a laboratory where scale, radicalism, and visibility were possible.

Into a scene split between Abstract Expressionism’s chest-beating machismo and Minimalism’s cool austerity, she brought something entirely her own: hallucinations rendered as dots and nets, obsessive patterns that replaced heroic gesture with relentless repetition. Donald Judd, then a critic, recognised her radical refusal of centre or hierarchy: where Pollock flung paint, Kusama covered canvases to obliterate herself.

Work by Yayoi Kusama

Style and influences

Kusama did not confine herself to the studio. During the 1960s, amid Vietnam protests, second-wave feminism, and sexual liberation, she staged “Happenings”: nude performances in public spaces where bodies were painted with polka dots – or, “marks of obliteration.” Participants became living sculptures, dissolving the boundaries between art and life, politics and spectacle. Sex, provocation and protest intertwined, from an orgiastic tableaux lampooning capitalist excess on Wall Street, to the 1969 antiwar event Anatomic Explosion, using body painting to confront war and social norms.

By the early 1970s, exhausted and under-recognised, Kusama returned to Japan. In 1977 she voluntarily admitted herself to a psychiatric hospital in Tokyo, where she continues to live and work. Far from retreat, this became the foundation for her late-career resurgence. From there, she produced paintings, sculptures, and installations at industrial scale, while also writing poetry and novels. The hospital is not an exile but an anchor: where Kusama transforms private compulsion into public monument.

Kusama drew from Japanese nihonga, European surrealists like Joseph Cornell, and American peers including Claes Oldenburg and Andy Warhol (whom she claimed borrowed her ideas). Her legacy is equally vital: Louise Bourgeois, Tracy Emin, Damien Hirst, and Sarah Lucas owe debts to her radical fusion of obsession, sexuality, and repetition. Contemporary immersive installations by Carsten Höller, teamLab, and Random International’s Rain Room bear her unmistakable influence.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Kusama's playful inflatables

Installation view of ‘Yayoi Kusama: You, Me and the Balloons’ at Aviva Studio

Kusama's most notable works

Infinity Nets (1958–)

Kusama’s Infinity Nets marked her arrival in New York. Canvases covered in tiny, looping, brush marks eschewed bold strokes in favour of a kind of cellular lattice that, when repeated obsessively, created an endless net-like surface. Painted obsessively for hours at a stretch, the nets reflect both hallucination and compulsion. Minimalists admired their seriality; Abstract Expressionists bristled at their refusal of bravura. The Nets foreshadowed much of her later work – from mirrored rooms to installations – proving accumulation can be as radical as expression.

Narcissus Garden (1966)

First staged at the Venice Biennale, Narcissus Garden featured 1,500 mirrored spheres scattered on the grass. Kusama, in a gold kimono, sold them to visitors, provoking outrage while critiquing art as commodity. Spectators became performers in their own reflection, implicated in cycles of desire and self-regard. The piece folds seduction and critique into a single gesture, decades before social media would replicate its self-reflective logic.

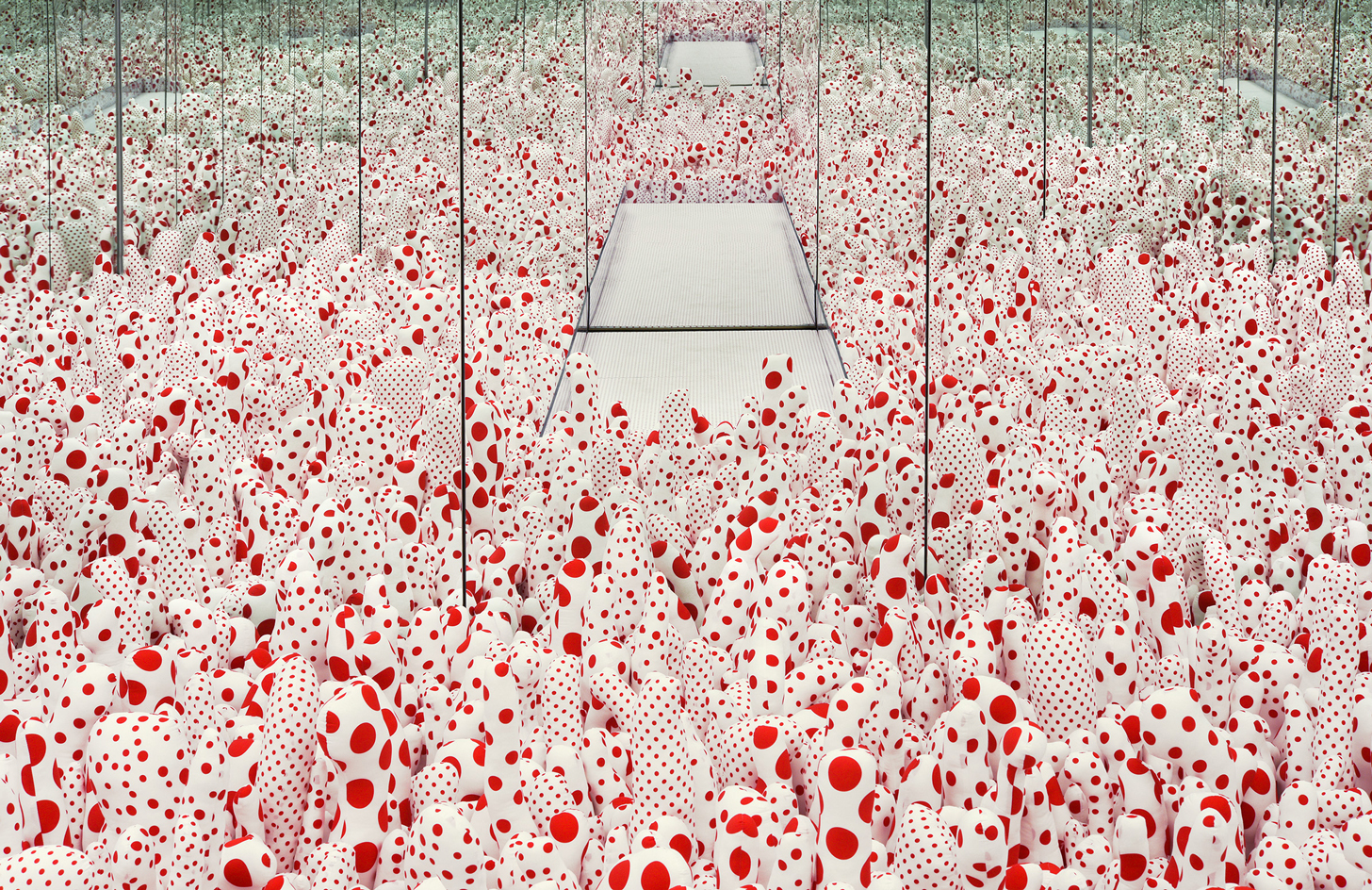

Infinity Mirror Rooms (1965–present)

The first, Phalli’s Field (1965), filled a mirrored chamber with hundreds of polka-dotted soft sculptures, multiplying into endlessness. Later rooms incorporated LEDs, water, or lanterns, but the conceit remains: immersion where selfhood dissolves into reflection. These works function on multiple registers – psychedelic spectacle, psychological allegory, feminist critique – and established Kusama as an architect of experience decades before “immersive art” became a marketing category. Infinity Mirror Rooms are available to visit at The Broad in Los Angeles and at the Yayoi Kusama museum in Tokyo.

Pumpkin (1990–)

The pumpkin, painted in childhood and later rendered in sculpture, is her most recognisable motif. Monumental or tabletop, yellow-and-black, it is part self-portrait, part talisman. In Japan, pumpkins carry folk associations with nourishment, grounding Kusama’s delirious hallucinations in earthy solidity.

Kusama's pumpkin

Kusama's 1965 mirrored infinity room Phalli's Field (Floor Show)

Kusama's legacy

Kusama endures because she refuses to separate the personal from the political. Dots are not decoration but acts of obliteration; mirrors are not spectacle but metaphors for a society in which identities multiply and dissolve. Her practice bridges modernism’s obsession with the infinite and today’s culture of repetition, spectacle, and anxiety.

Now in her nineties, Kusama is celebrated worldwide, her exhibitions drawing record-breaking crowds, and collaborations with fashion and design cementing her patterns as global trademarks. Cynics might read this ubiquity as commodification, but it also affirms her lifelong project of dissolving art into everyday life. If her 1960s Happenings once scandalised institutions, today’s Kusama stands inside them, filling museums with queues that wrap around the block.

At the centre is an artist who has spent seven decades wrestling hallucinations into form, insisting private visions can become collective experience. Kusama’s dots, nets, pumpkins, and mirrors are playful, obsessive, and inexhaustibly strange. In her world, infinity is not an abstraction but a room you can step into – and perhaps never leave.

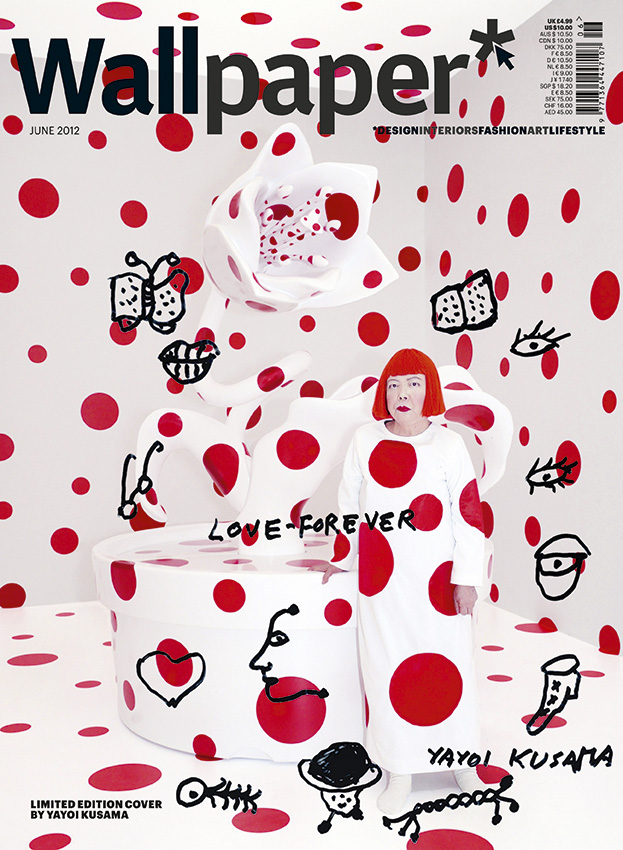

Kusama's June 2012 issue of Wallpaper*

Finn Blythe is a London-based journalist and filmmaker