In Norway, discover 1000 years of Queer expression in Islamic Art

'Deviant Ornaments' at the National Museum of Norway examines the far-reaching history of Queer art

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Islamic art can be misunderstood, particularly in the idea that it entirely forbids depictions of living beings. This view, however, ignores the historical complexities involved. In truth, animals and humans have been shown in Muslim culture’s art, particularly in secular and private contexts (though such representations are rare in religious settings).

This complicated legacy, alongside the exploration of Queer identities throughout Islamic art history, has received little attention in mainstream discourse. Recently, museums and galleries have begun highlighting these narratives for the wider public, including, most notably, at The National Museum of Norway with its new exhibition, Deviant Ornaments. Spanning over a thousand years and four continents, the show features more than 40 works by 30 artists and craftspeople, including textiles, wall tiles, decorative plates, illustrations, as well as contemporary paintings, sculptures, and videos, illustrating the intricate and rich history of queer expression in Islamic art.

Ramin Haerizadeh, Rokni Haerizadeh and Hesam Rahmanian, Dance after the Revolution, from Tehran to LA, and Back, 2020.

Curated by Noor Bhangu, a scholar who developed the concept of Deviant Ornaments during her PhD, the exhibition is also influenced by her personal experiences as a racialised South Asian woman living in Norway. The project began with an exploration of queer history alongside Islamic art history, noting that both fields experienced a significant rupture in the 19th century, characterised by a decline in artistic production. ‘People from this region no longer had a script or understanding of sexuality because they were damaged by colonisation. So this rupture was contemporaneous in both disciplines,’ Bhangu explains.

Divided into three themes - Abundance, Ornamentation and History of Sexuality - Deviant Ornaments highlights the erotic turn in the field to challenge rigid ideas of gender, sexuality, and cultural heritage, while also confronting the difficult legacies of Orientalism and colonialism. The exhibition bridges these perceived ruptures by showcasing works by both historical and contemporary artists engaged with ornamental aesthetics from diverse cultural, political, and geographical backgrounds.

Works on show include the 3D-printed work Amorous Couple (2025) by Rah Eleh, commissioned by the National Museum of Oslo. This piece references a 17th-century Mughal miniature housed at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, noted as one of the few visual portrayals of lesbians with dildos in Islamic art history. The work portrays two queer figures. One is identified as the king’s guard holding the dildo, while the other is an aristocrat and one of the king’s wives. In historical texts, such guards are documented to provide pleasure to the wives in secret women’s quarters using objects like a cucumber.

Shahzia Sikander, Promiscuous Intimacies, 2020

Bhangu worked in close dialogue with Eleh, stating that there is a passage in a manuscript by Venetian diplomat Ottaviano Bon that mentions the banning of cucumbers and carrots. While he doesn’t explicitly name sapphic pleasure, he was clear that such things were outlawed. ‘There's very little reference to female homosexuality and sexuality. We have more representations of men, both visual and textual, but what we have instead in terms of female histories, feminist histories, are references and suggestions. This manuscript is lovely because it also visualises what we're talking about.’

In room two, there is an eye-catching contemporary painting titled Kasbah (2008) by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. The artwork features a Black figure wrapped in a white shroud, gazing directly ahead. Their eyes seem to follow viewers around the room, and the sitter's gender is ambiguous, reflecting a fluid identity. The title Kasbah refers to a citadel or the Arab quarters of a North African city and it references Édouard Manet’s Orientalist painting Olympia (1863), which depicts a white woman attended by her Black maid, highlighting the racist and sexual legacies of Western art. With Yiadom-Boakye’s painting, the figure confidently occupies space.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Deviant Ornaments installation image of: Unknown artist, Fritware bowl decorated with colors and gold leaf over white glaze, approx. 1200.

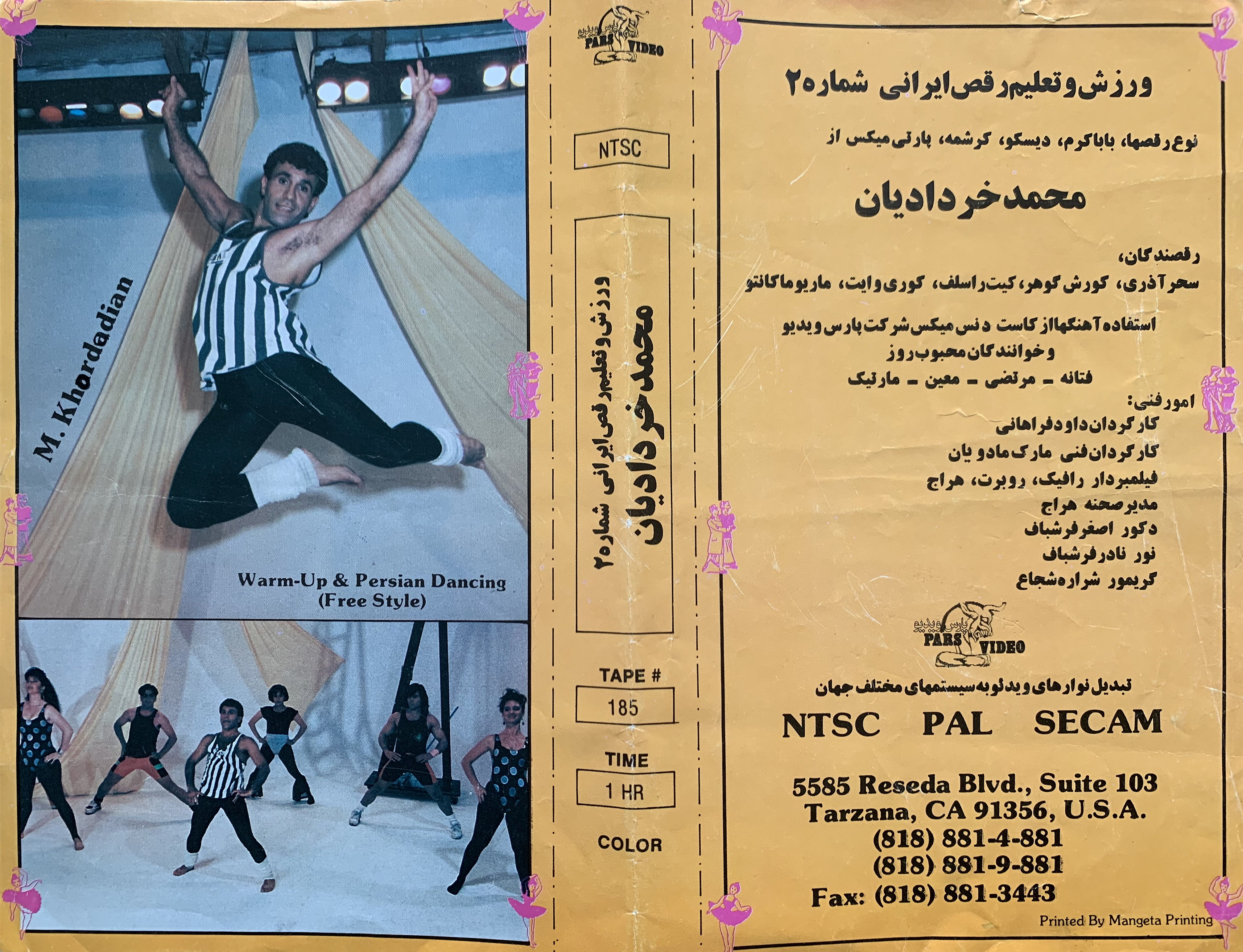

Elsewhere in the room is a film project, Dance after the Revolution from Tehran to LA and Back (2020) by Iranian artists Ramin Haerizadeh, Rokni Haerizadeh, and Hesam Rahmanian, presenting archival footage showing the influence of exiled dancer Mohammad Khordadian, who smuggled VHS tapes of aerobic cabaret to preserve Iranian cultural identity through dance after public dancing was banned. The work provides a look at how Islamic nationalism is intertwined with diasporic modes of survival.

Further in, Parisian-born artist Damien Ajavon’s textile sculpture, Chemin vers Oslo (2025), explores the opacity and poetics of textiles, linking them to queer and Afro-diasporic representations. The woven textile is also decorated with the Hand of Fatima and the protective eye amulet to safeguard the labour the show presents, acknowledge its complex histories, and serve as a protective layer for the exhibiting artists, helping them face criticism and challenges from many sides. ‘It's not that we're scared about the Muslim community taking offence, but this exhibition is challenging Islamophobia as well,' says Bhangu.

Palestinian American artist Kiki Salem’s digital print wallpaper for the mediation station installation A Love Letter to Maria, Foziah, and Fatima (2025) is named after her three grandmothers. She was inspired after discovering a selection of their dresses during her summer trip to the West Bank, drawing from the designs of the Tatreez thobes to create patterns for the wallpaper. The work encourages visitors to sit within the arched space, write a love letter on the provided scroll and share a tender moment in the exhibition. 'It was really important to also include Kiki's work as a layer to talk about how ornaments continue to migrate across different spaces and also how contemporary artists can negotiate with their cultural and familial heritage,' Bhangu says. Håkon Lillegraven, the Public Programme and Education Curator at the National Museum, adds that the love letter scroll will be kept in the museum’s archive after Deviant Ornaments ends and will be part of the documentation. 'We specifically say write in the language closest to your heart so that after the show, we'll have this documentation of what languages people write in, who they write to, and what they wrote. We hope that this archive will help us learn more about the exhibition.'

Deviant Ornaments is at the National Museum of Norway until 15 March 2026