Jenny Saville’s major exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery is raw, powerful and sublime

Fifty works, from the course of the artist’s career, are brought together for ‘Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting’ in London

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

The first impression of entering Jenny Saville’s major retrospective at the National Portrait Gallery in London is one of raw, ample flesh. Viscerally rendered, luscious expanses of flesh create a vulnerable yet powerful aura around Saville’s women, who fill her vast canvases, unabashedly and gloriously taking up space.

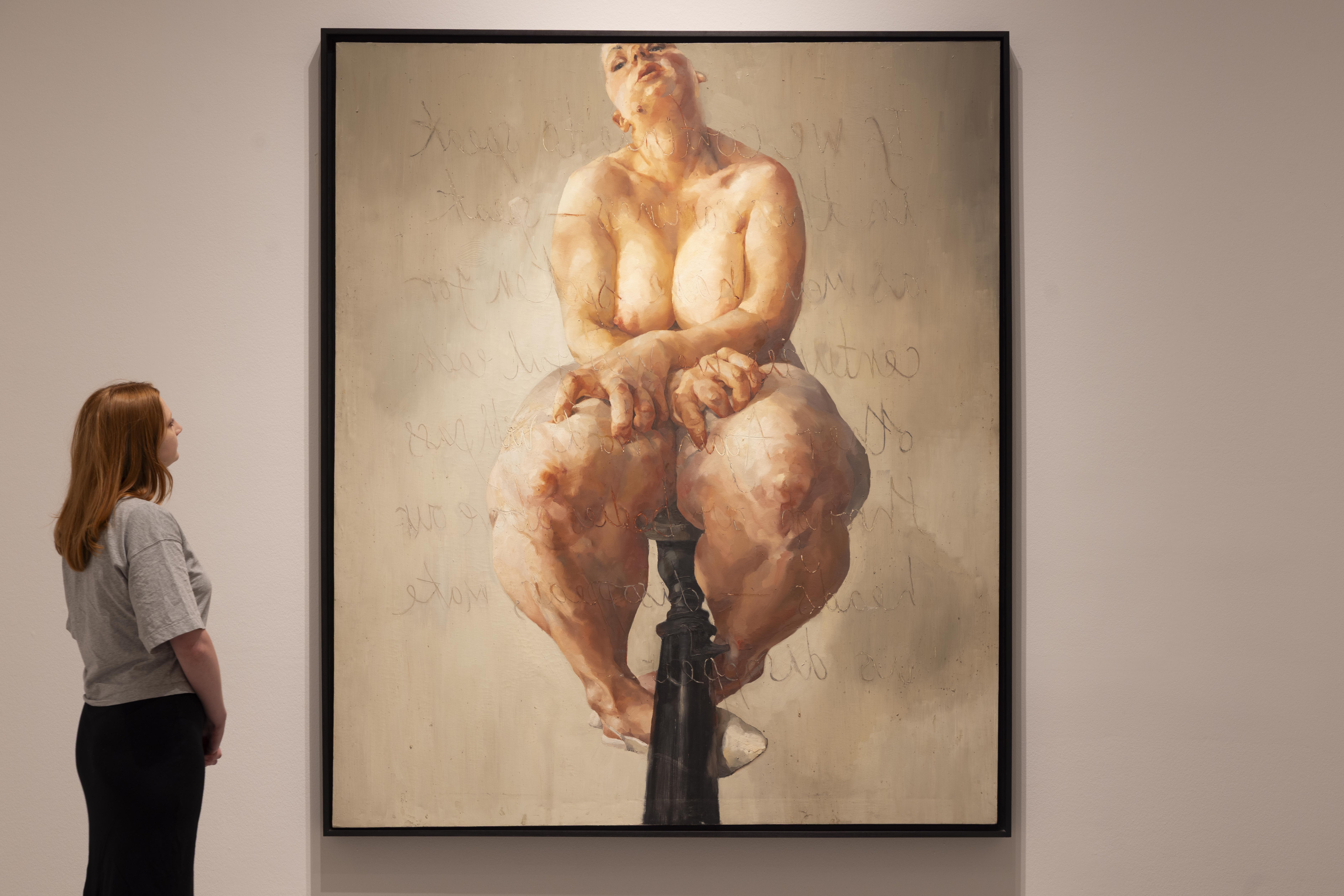

Installation view, Jenny Saville, Propped, 1992, private collection

‘Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting’ (until 7 September 2025) is not a traditional exhibition of portraiture. It spans her career to date, beginning in the 1990s, following her graduate show at the Glasgow School of Art – from which Charles Saatchi purchased Propped and commissioned a new body of work for his own gallery space – and taking us through to work created in 2024.

Taken as a whole, the 50 works on display, comprising both paintings and drawings, present a rethinking of traditional figurative portraiture, and instead are more ‘portraits of painting’, as Saville has referred to them in the past.

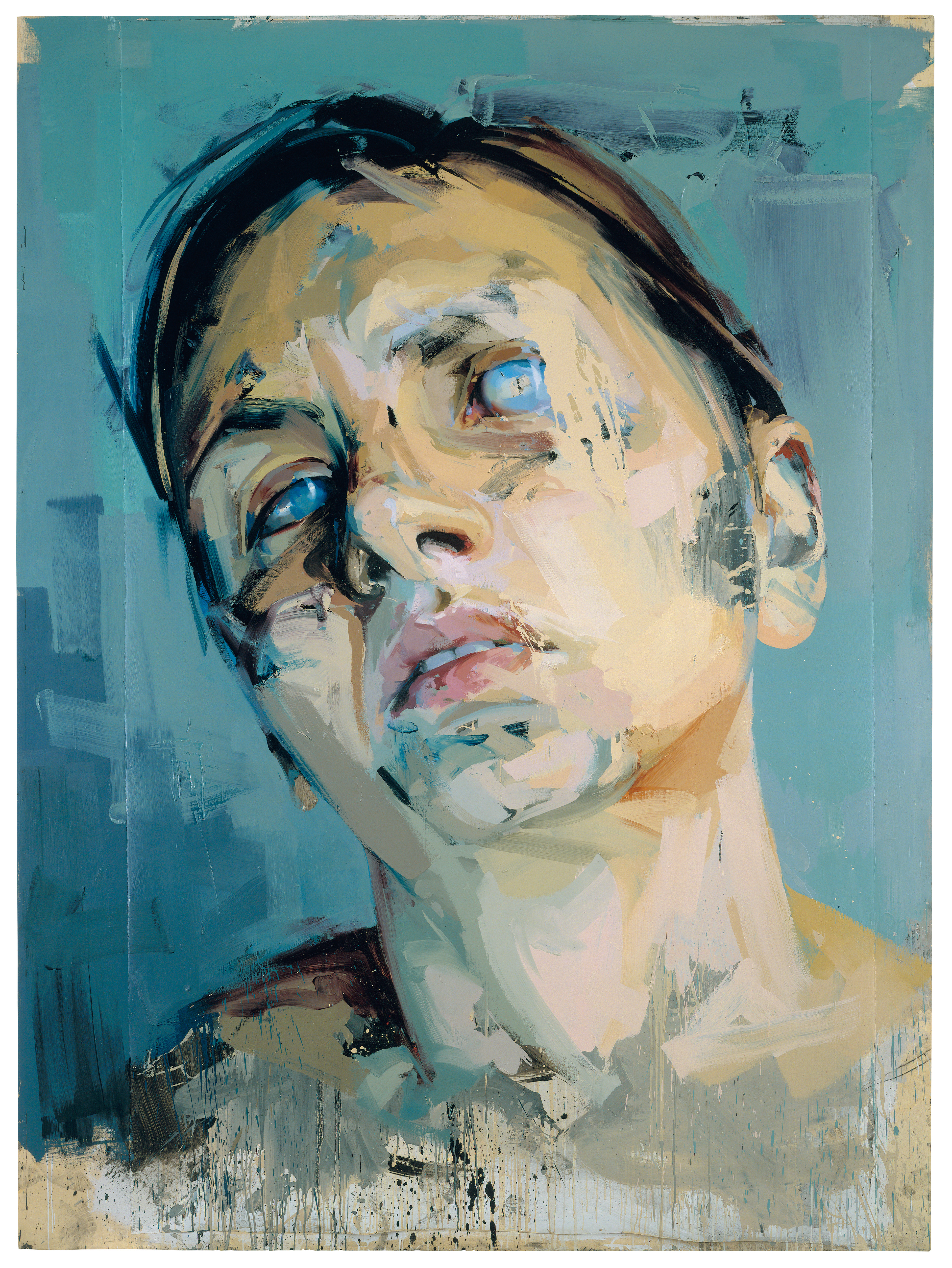

Here, we go from the defiant, direct Propped – not a self-portrait, but a ‘loaning her body to herself’, says Saville in the notes, to the abstract, experimental Reverse. This zooms us into the head of a woman, seen on its side, flipping our perspective, and invites us to lose ourselves in the thick strokes of the paint and the work’s fluid, blurred force. In Rosetta II, the figure’s head avoids our gaze, lost in contemplation but still zinging with movement, created from Saville’s combination of painting techniques – ‘I threw a tinted primer to make a splash up the right side of her cheek,’ she says. Saville was inspired by Picasso’s La Celestina, an austere work depicting a woman blind in one eye; in her quiet, forceful presence, she embodies an unknowable mysticism.

Jenny Saville, Rosetta II, 2005-2006, private collection

Throughout the show, Saville’s unapologetic, sublimely rendered portraits of women’s bodies avoid conventional representations, speaking instead to a different canon of history. She is inspired by Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud, and also contemporary artists, notably Cy Twombly and Willem de Kooning. Like de Kooning, Saville takes Rubens’ voluptuous folds and curves and imprints the ‘flaws’; a woman’s breasts, which fall magnificently, coils of pubic hair and round buttocks are a love letter to the reality and power of the female body. For de Kooning, ‘flesh was the reason why oil painting was invented’. In her works’ embrace of colour, movement and abstract forms, it is true for Saville too.

Jenny Saville, Ruben’s Flap, 1998-1999, The George Economou Collection

Saville paints her portrait works from photographs, rather than life, something she says she gained the confidence to do after looking at Bacon’s process. It offers her greater freedom to explore poses a life model would not be able to hold, and the opportunity to zone in on the details of a face, as well as enabling her to paint in the absence of a life model’s availability – although, as she has notes, you lose a little of the depth, particularly in the shadows.

Saville’s photographs are taken from a variety of sources. In Stare, she studied the image of a woman with a birthmark on her face, found in a medical book. She observed plastic surgery operations in New York, studying how the flesh becomes a moveable thing, pulled up and pinched, something that became crucial to her own work, which can distort scale and angle, seen especially in Ruben’s Flap. In Stare, colour becomes a dynamic force, catching the light and reinterpreting the angles of the face.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Jenny Saville, Stare, 2004-2005, The Board Art Foundation

In the exhibition, medical imagery segues into Saville’s motherhood works, which capture the woman’s body at its most primal, pregnant and squashed by squirming toddlers. Intimate and so closely observed as to be almost tangible, the works draw on the artist’s own experience, combining her influences of Renaissance drawings of Madonna and child, Rembrandt’s ink drawings of mothers and children, and her own experience of the instinctive movements of a child’s body. The works also mark the growing importance of drawing for Saville, which she found easier to stop and start around the needs of her children, as opposed to painting, which requires greater clear-up. Raw, honest, profound and visceral, they speak for us all.

‘Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting’ 20 June – 7 September 2025 at the National Portrait Gallery, npg.org.uk

Jenny Saville, Hyphen, 1999, Private collection

Hannah Silver is a writer and editor with over 20 years of experience in journalism, spanning national newspapers and independent magazines. Currently Art, Culture, Watches & Jewellery Editor of Wallpaper*, she has overseen offbeat art trends and conducted in-depth profiles for print and digital, as well as writing and commissioning extensively across the worlds of culture and luxury since joining in 2019.