Generous gestures: Linder’s Dovecot collaboration, at British Art Show 8

Leeds Art Gallery has given itself over entirely to the eighth edition of the British Art Show. A generous gesture, but BAS – organised by Hayward Touring – only happens once every five years and there’s a lot to fit in. The exhibition – which over the next 15 months will move on to Edinburgh, Norwich and Southampton – has been curated by Anna Colin and Lydia Yee and includes works by 42 artists. Twenty-six of those have created new works specifically for the show.

Colin and Lee say that a key theme emerged after conversations with participating artists: materiality. No surprise there, perhaps, as investigations of the material and the immaterial seems to be a current fascination across art and design. And many of the works on show in BAS8 bring the those increasingly blurred disciplines together.

Martino Gamper’s Post Forma, one of the new commissions for the show, is a celebration of upcycling. And Gamper has called on Yorkshire artisans of various stripes; specialists in weaving, bookbinding, cobbling and chair caning. In addition, he is inviting members of the public to bring along broken objects, loved or unloved, which will then be repaired and recrafted. (There will also be workshops at Hepworth Wakefield and the Yorkshire Sculpture Park.)

Stuart Whipps, meanwhile, has recruited former workers of the Longbridge plant in Birmingham, who will restore a 1979 Mini during the course of the show. Anthea Hamilton has created freestanding sculptures which also function as ant farms.

There are also new works from Ahmet Ogut, a collaboration with Liam Gillick, Susan Hiller and Goshka Macuga; Simon Fujiwara; and Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin; as well as UK premieres for works by Ryan Gander, Cally Spooner and others.

A particular highlight of the show – as those who have already got their hands on a copy of the very special 200th edition of Wallpaper* will know – is Linder’s collaboration with the tapestry and rug makers at Edinburgh's Dovecot Studios. Titled Diagrams of Love: Marriage of Eyes, the rug will also play a part in Children of the Mantic Stain, a new ballet based on an essay by surrealist Ithell Colquhoun, to be performed, and adapted, at various points along BAS’s tour by Northern Ballet. We spoke to Linder and Dovecot Studios’ rug tufter Dennis Reinmüller before the opening of BAS8 about the collaboration.

W*: Did you come up with an initial design and present it to the Dovecot team or develop the idea as you went along?

Linder: I arrived at Dovecot Studios last year with two years' of research files that had accumulated during my recent residency at Tate St Ives. I knew that the rug had to be radically different from every other rug that I’d ever seen, both in its design and in its intended function. I was asking a lot from the structure of the rug and a lot from the rug tufters; the rug had to be capable of being viewed as a static display within the galleries of the British Art Show 8 and also as a choreographed element within the Children of the Mantic Stain ballet that the rug would be an integral part of. I had various ideas for the design of the rug but it was more the mood of the object that was of utmost importance. I’d been researching the life of the surrealist Ithell Colquhoun – the ballet takes its name from an essay that she wrote in 1952 – and I wanted the rug to have an hallucinogenic – mantic – quality to it, so that it could shapeshift wherever it travelled to. A magic carpet by any other name.

What was the original inspiration for the Dovecot Studio design?

I’d recently stayed in the artist’s apartment at Raven Row Gallery. The apartment used to belong to the late Rebecca Levy who had lived there for most of her adult life and the apartment is still exactly how it was when Rebecca died. I fell in love with the 1970s carpets there; they reminded me of similar ones that my parents used to have. I incorporated two different carpets of Rebecca’s and arranged them within concentric circles. I then added glam rock blue eyes everywhere, mimicking a peacock’s tail seen on acid.

How was the design adapted during the process?

We decided to base the design on the photographs that I’d taken of the carpets in situ at Raven Row so that they were already at one remove from the originals. We also made a series of decisions on how the designs would vary in scale and tone within each concentric circle. Then the radical act – the cutting up of the rug into a spiral, that could both lie flat and also be draped and reconfigured any which way around a ballet dancer or suspended within a gallery space. We also gave much thought to the jute backing of the carpet, wanting to create a parity of glamour with the tufted surface. Gold lamé was the final choice. In the ballet, Hollywood will hide under the rug until the final scene.

The weaver and tufters are designers and artists in their own right. How did that collaborative process work?

From the very beginning, the tufters at Dovecot Studios were a vital part of the creative process. We had endless conversations about the mood of the rug before we even approached the final design. The rug had to be capable of shapeshifting within any given environment and it had to be robust enough to withstand a one-hour ballet. The tufters gave their all in making Diagrams of Love: Marriage of Eyes happen. Now, a whole other phase of collaboration is happening with Northern Ballet and with Christopher Shannon, who will design the ballet costumes. The choreographer Kenneth Tindall and I are presently working out how to choreograph a rug. Thankfully the rug has such presence that it seems to be teaching us how it wants to move – we just have to let it have its space with the dancers and see what happens.

Had you worked with rug making before?

I designed my Linderama rug for Henzel Studio Collaborations in 2014 – the design was based on a photomontage that I made in 1978. This collaboration generated ideas for future possibilities of rug making within my practice. I’d suggested that whoever bought Linderama should think of it in terms of a textile base for creating an assemblage of their own; you could place a food processor upon the rug and immediately extend the meaning of the work. I like the thought of a daily dialogue with Linderama so that the piece is kept alive with possibilities within the domestic sphere.

How different is designing rugs as a discipline? What adjustments do you have to make and what do you think are its strengths as a form?

My trick was not to be too overwhelmed by the history of the discipline; I wanted to see the rug in a very different way to how anyone else had looked at a rug before. Following the Henzel Studio collaboration, I also wanted to see yet again how my lifelong practice of photomontage could be translated into tufts of wool. This was then up to the highly creative tufters at Dovecot Studios; they rose to the challenge and surpassed all my expectations. Asking them to then cut up the rug felt almost criminal. I use surgeon’s scalpels to create photomontages, so I know that one slip of the blade can destroy a work. Thankfully the tufters and I have nerves of steel and the cut was sublime in its precision. It also completely liberated the rug; it now it has agency to take on which ever shape it pleases – mantic Carpets’R’Us.

Can you describe the development of the rug?

Dennis Reinmüller: Linder arrived with a whole library of poetic and metaphoric links, which she shared very generously with us. The aim was to create an object that is the manifestation of her research – this started days of discussions, sharing of knowledge and associations. Linder was quite clear from the very beginning that this should not be an ordinary rug: it should be a hallucinogenic shapeshifter, a seductive serpent emerging from a fever dream – dangerous and alluring in equal measure. As we have been experimenting how far we can push the rug as an art object at Dovecot, this prospect was exciting for us.

How was the design adapted during that process?

There are always countless stages of adaption, especially with a piece that pushes the medium as much as this one does. After Linder decided on the look and mood of the rug our interpretive work began. How much carving will we do? Just how wild should the feral polyester eyelashes be? Have we ordered in enough gold lamé? Is this combination of colour inducing enough of a psychedelic episode?

You are all designers and artists in your own right at Dovecot. How did that collaborative process work?

Knowing that everyone has a distinct voice that can come together as a whole is key here. I could point to very specific elements of the piece and attribute it to either Linder, the weaver Jonathan Cleaver, me or our newest rug tufter Vana Coleman, but also Barbara Hepworth, Ithell Colquhoun, the 1920s actress Alla Nazimova or the cultural and economic realities of Linder’s teenage years. The aim is always to create an object that resonates within its cultural weave, and if it is a great piece it will send shockwaves through it.

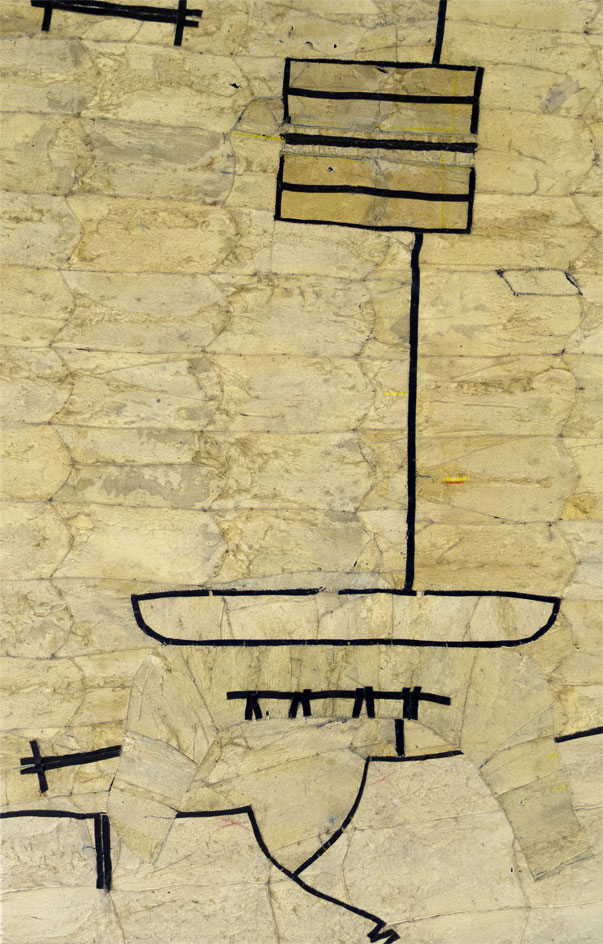

’I wanted the rug to have an hallucinogenic – mantic – quality to it, so that it could shapeshift wherever it travelled to. A magic carpet by any other name,’ says Linder. Pictured: Diagrams of Love: Marriage of Eyes (detail), by Linder Sterling and Dovecot Studios, 2015 . courtesy Stuart Shave/Modern Art and Dovecot Studios Ltd

The rug, as those who have already got their hands on a copy of the very special 200th edition of Wallpaper* will know, will play a part in Children of the Mantic Stain, a new ballet based on an essay by surrealist Ithell Colquhoun. Pictured: Diagrams of Love: Marriage of Eyes (detail), by Linder Sterling and Dovecot Studios, 2015 . courtesy Stuart Shave/Modern Art and Dovecot Studios Ltd

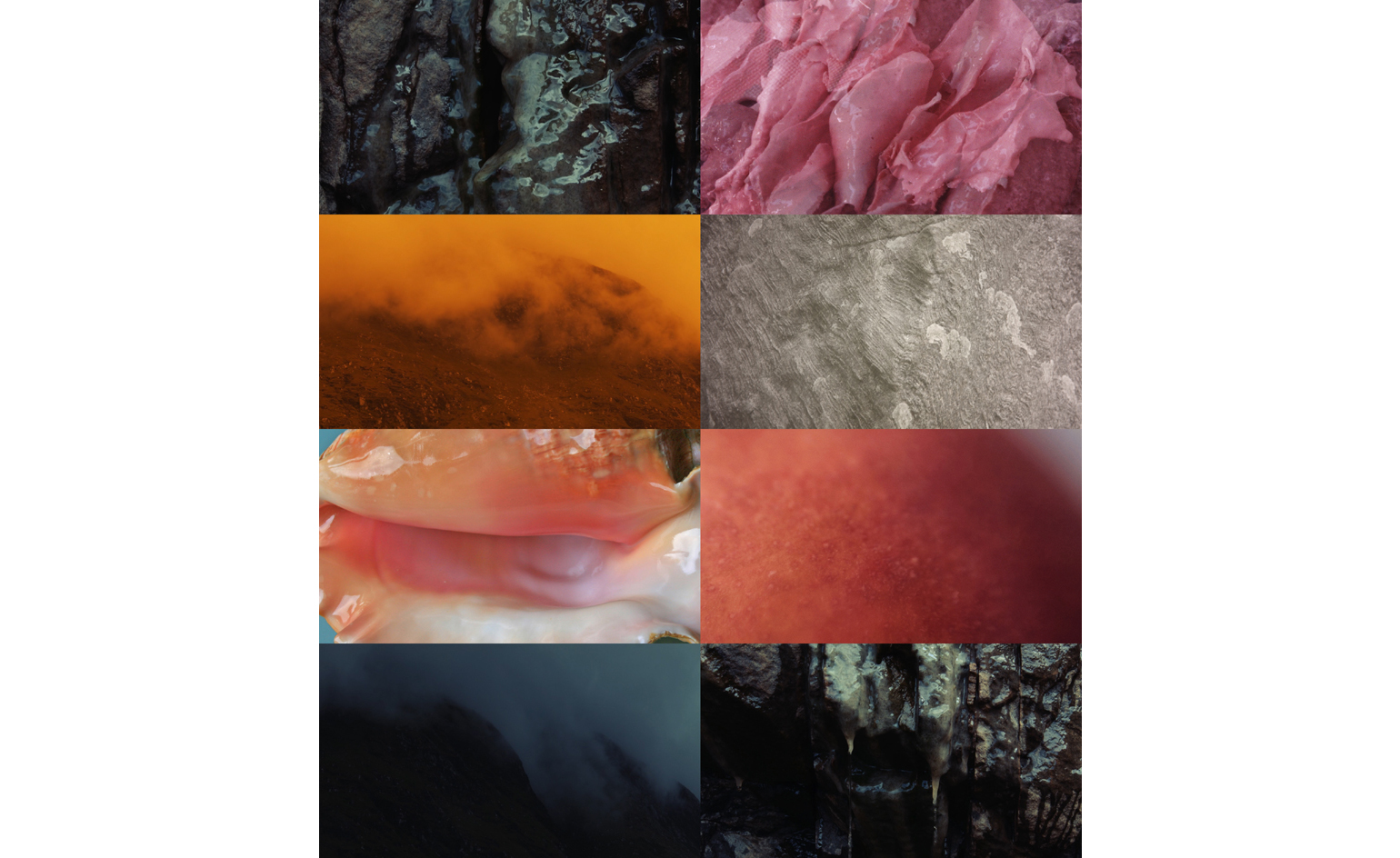

BAS8 – which over the next 15 months will move on to Edinburgh, Norwich and Southampton – has been curated by Anna Colin and Lydia Yee and includes works by 42 artists. Pictured: Fabulous Beasts, 2015. Courtesy the artist and Proyectos Monclova, Mexico

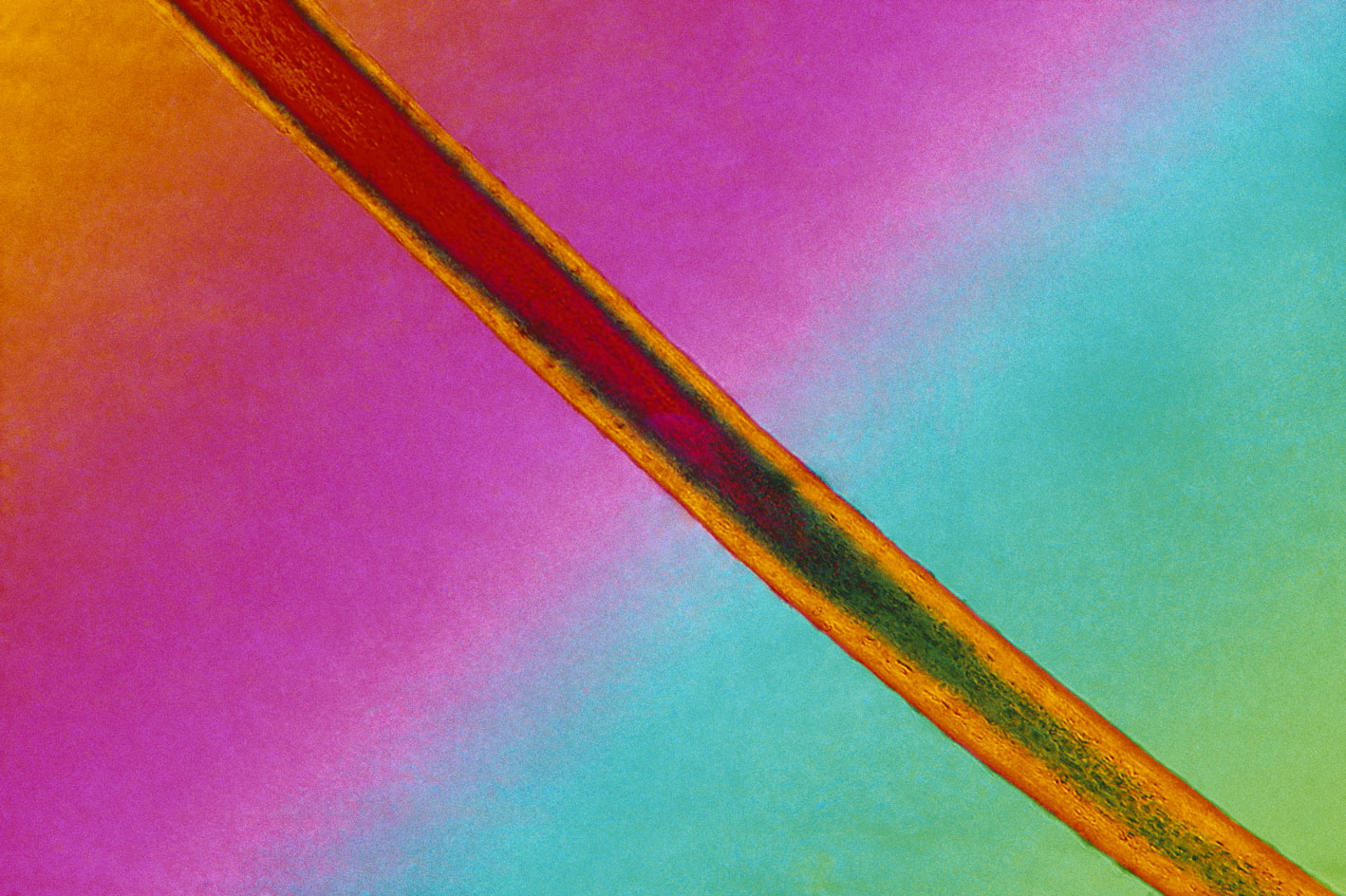

Trace Fiber from Freud’s couch under crossed polars with Quartz wedge compensator (#2), 2015. Courtesy the artists and Lisson Gallery, London

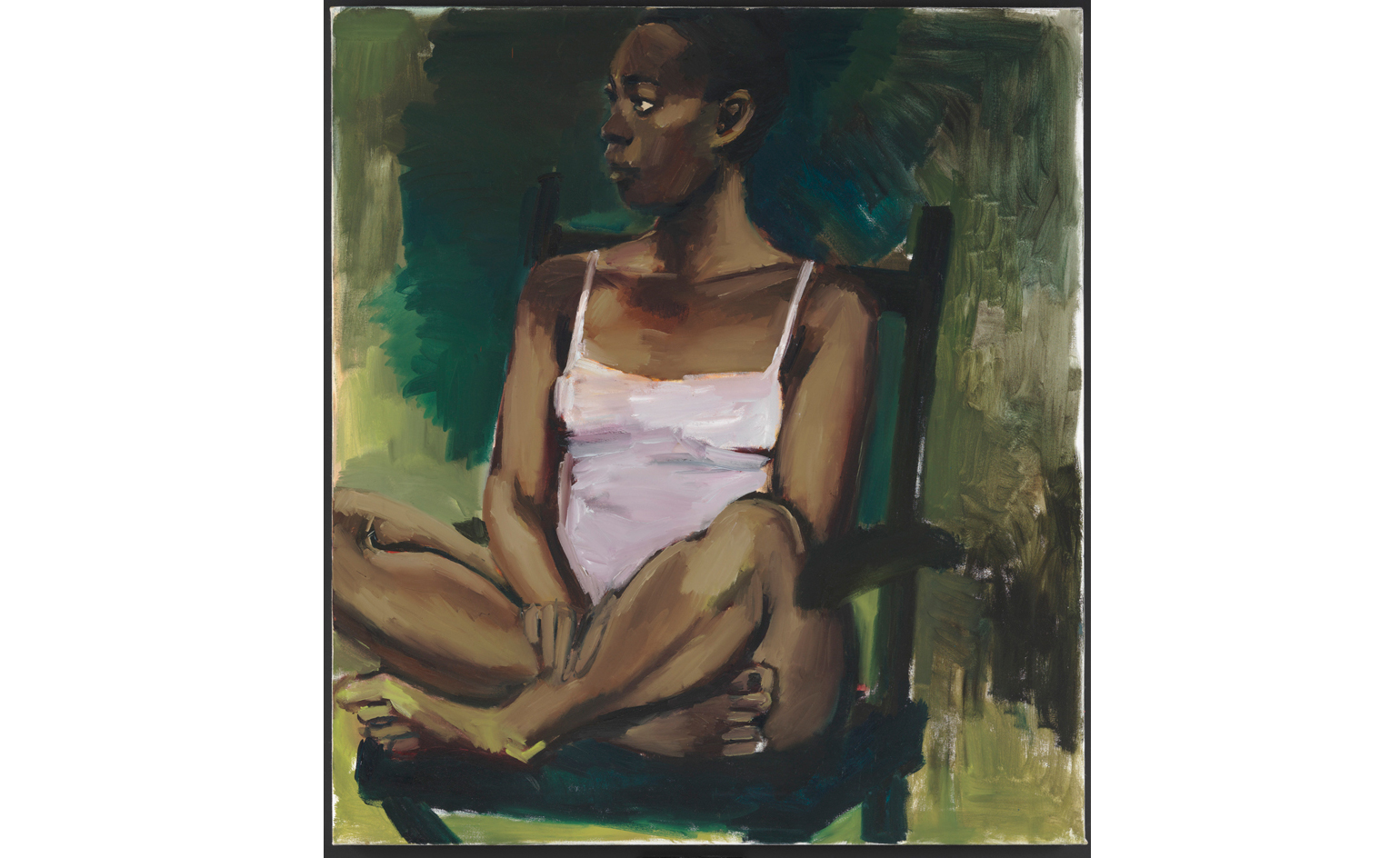

Fatima, 2015. Courtesy the artist

Sequencer (production still), 2015. Courtesy the artist and Matt’s Gallery London

Century Egg (film still), 2015. Courtesy the artist and Limoncello Gallery

A Head for Botany, 2015. Courtesy Corvi-Mora, London and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

INFORMATION

’British Art Show 8’ is on view until 10 January 2016

ADDRESS

Leeds Art Gallery

The Headrow

Leeds, LS1 3AA

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.