Forty years of the Barbican Centre: an art utopia made concrete

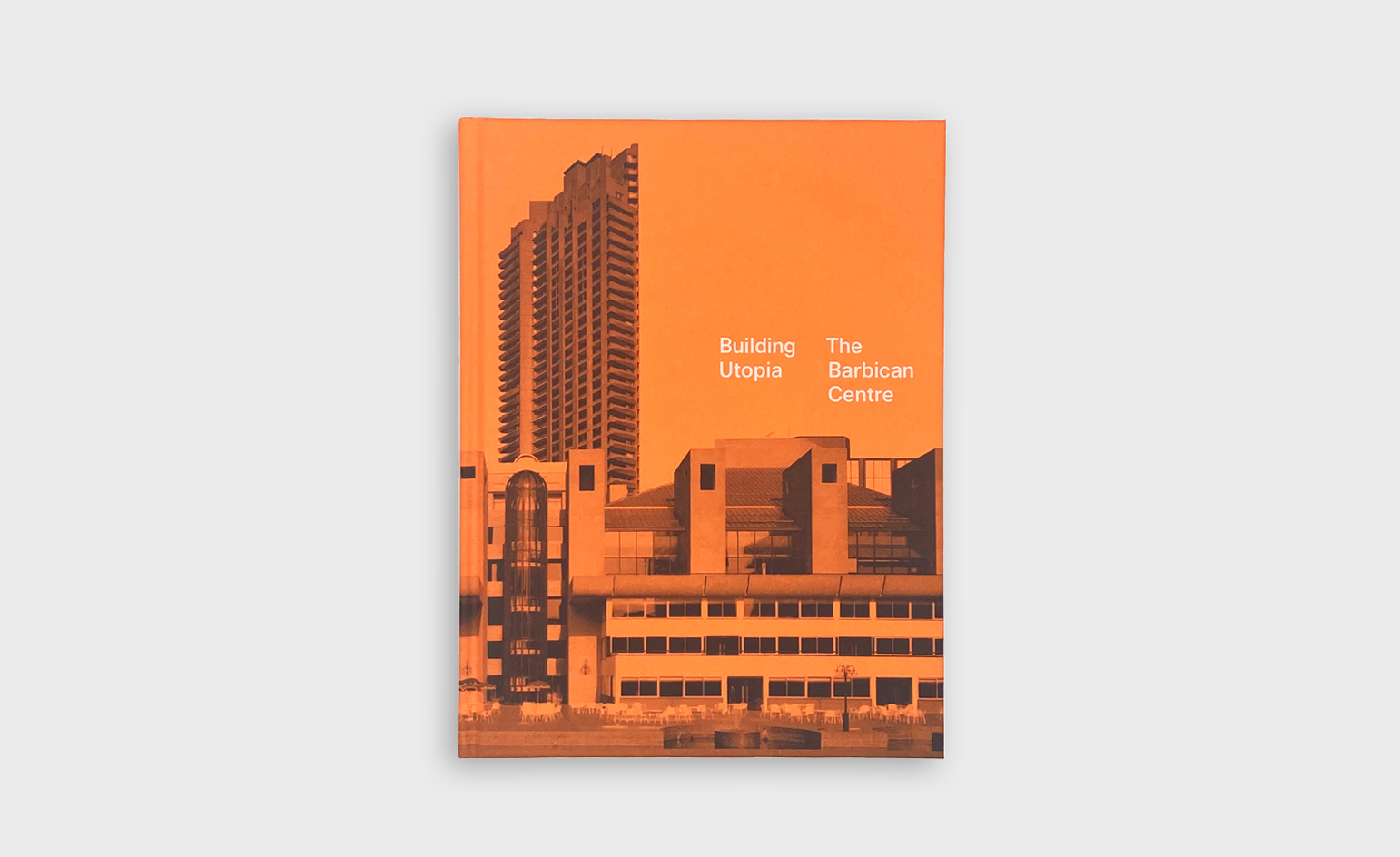

Building Utopia: The Barbican Centre, published to coincide with the institution’s 40th anniversary, explores the birth of the Barbican, its storied history and its unparalleled impact on contemporary arts and culture

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Utopia, by definition, can never be reached. When Thomas More coined the term in 1516, he imagined an ideal world, a self-contained community where people shared the same culture, values and way of life. ‘Utopia’ was also a pun, based on almost-identical Greek words for ‘no place’ and ‘a good place’.

The Barbican Centre was, and remains, a place where utopian ideas are made tangible. Designed by young architecture firm Chamberlin, Powell and Bon, the labyrinthine complex symbolised a corner of London rising from the war-torn ashes; an example of the shifting worlds of arts and culture in the post-war era, and an icon of modern, democratic living. Under a single, 40-acre architectural vision, it encompassed theatre and dance, music of all genres, visual arts, cinema and education, setting its stages for a wide range of artists, communities, audiences and visitors.

The Barbican Centre: ‘one of the modern wonders of the world’

When it opened in 1982, its reception ranged from scalding hot to ice cold. Some applauded its brave futurism (

even Queen Elizabeth II hailed it as ‘one of the modern wonders of the world’); others despised its brazen brutalism. Through fame and infamy, brutal name-calling and calls for its demolition, 40 years later, it remains a melting pot of international arts, and one of the most sought-after residential postcodes in Europe.

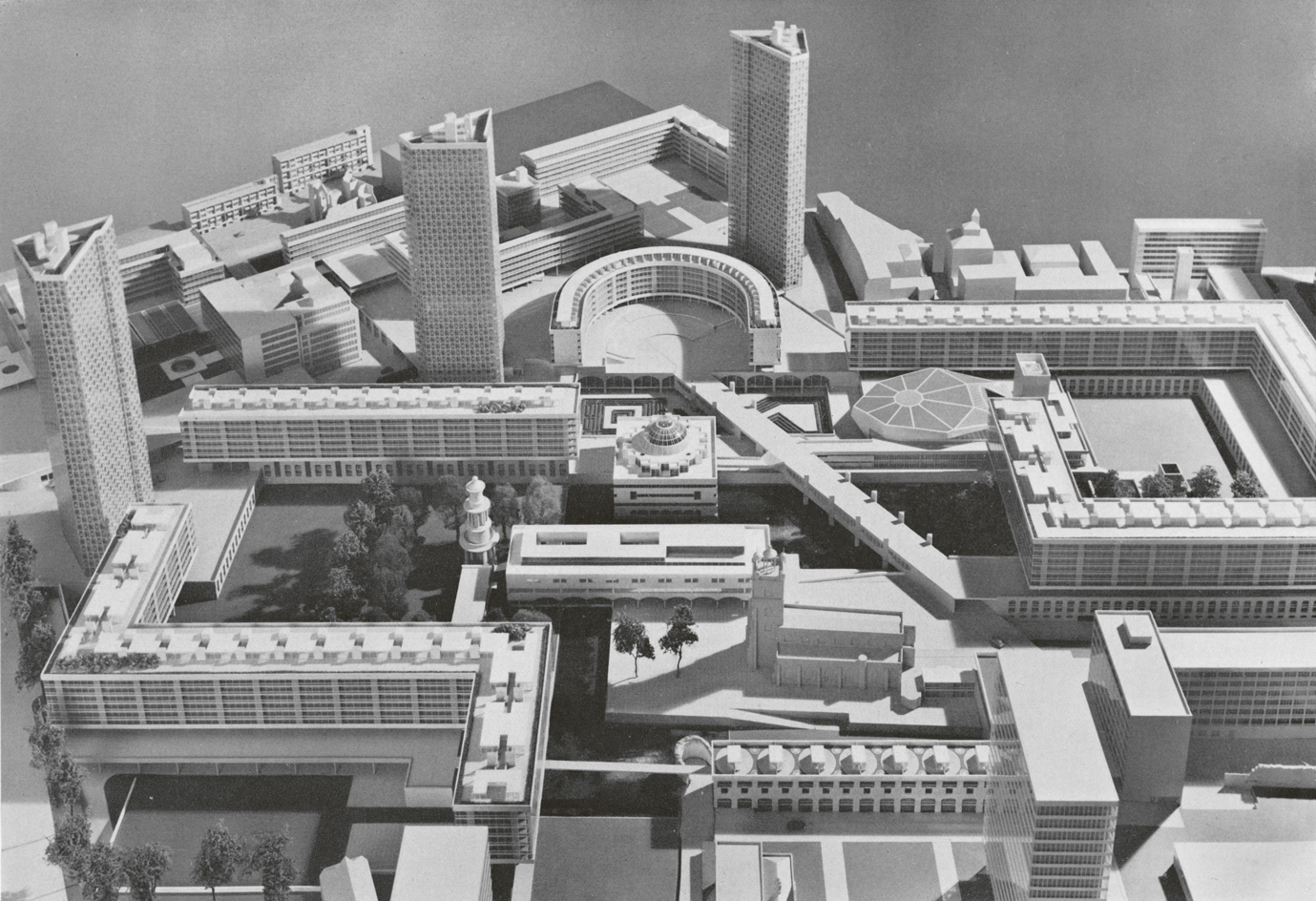

The model of the scheme, including a diagonal road across the site, and the proposed use of the circular Coal Exchange. Both were later taken out of the plans.

As Nicholas Kenyon, editor of new book Building Utopia: The Barbican Centre, notes in his preface: ‘Some have hated it, some have loved it, but millions have made use of the Barbican over four decades of near-continuous activity, and have come to value its profound contribution to civic and urban life.’

Published by Batsford, Building Utopia coincides with the Barbican Centre's 40th anniversary and explores the history of this inimitable institution and the blueprint to its longevity. ‘I think the secret of the Barbican is to always be uncompromising in its search for quality and variety, believing that there’s no conflict between excellence and popularity,’ says Kenyon, who served as managing director of the Barbican Centre from 2007 to 2021. ‘The Barbican has always cast its net wide to gather in the most international of the arts, and to provide [them] at reasonable prices to the widest possible audience.’

The book contains rare illustrative material from the Barbican’s archives, some never before seen in print. ‘The biggest surprise to me in looking through the archives was not how long it took – we’d always known that the Barbican as a building project took ages! – but the number of changes there were in the design as the arts centre emerged as a priority,’ Kenyon reflects. ‘There are literally thousands of architects’ drawings of the details. I looked and looked for evidence of the Barbican myth that the building was only approved by a one-vote majority in the City, but I couldn’t find it. However, there were many close votes as the project proceeded.’

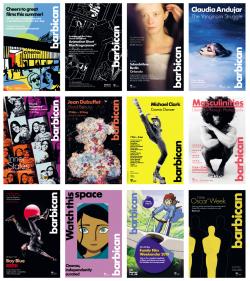

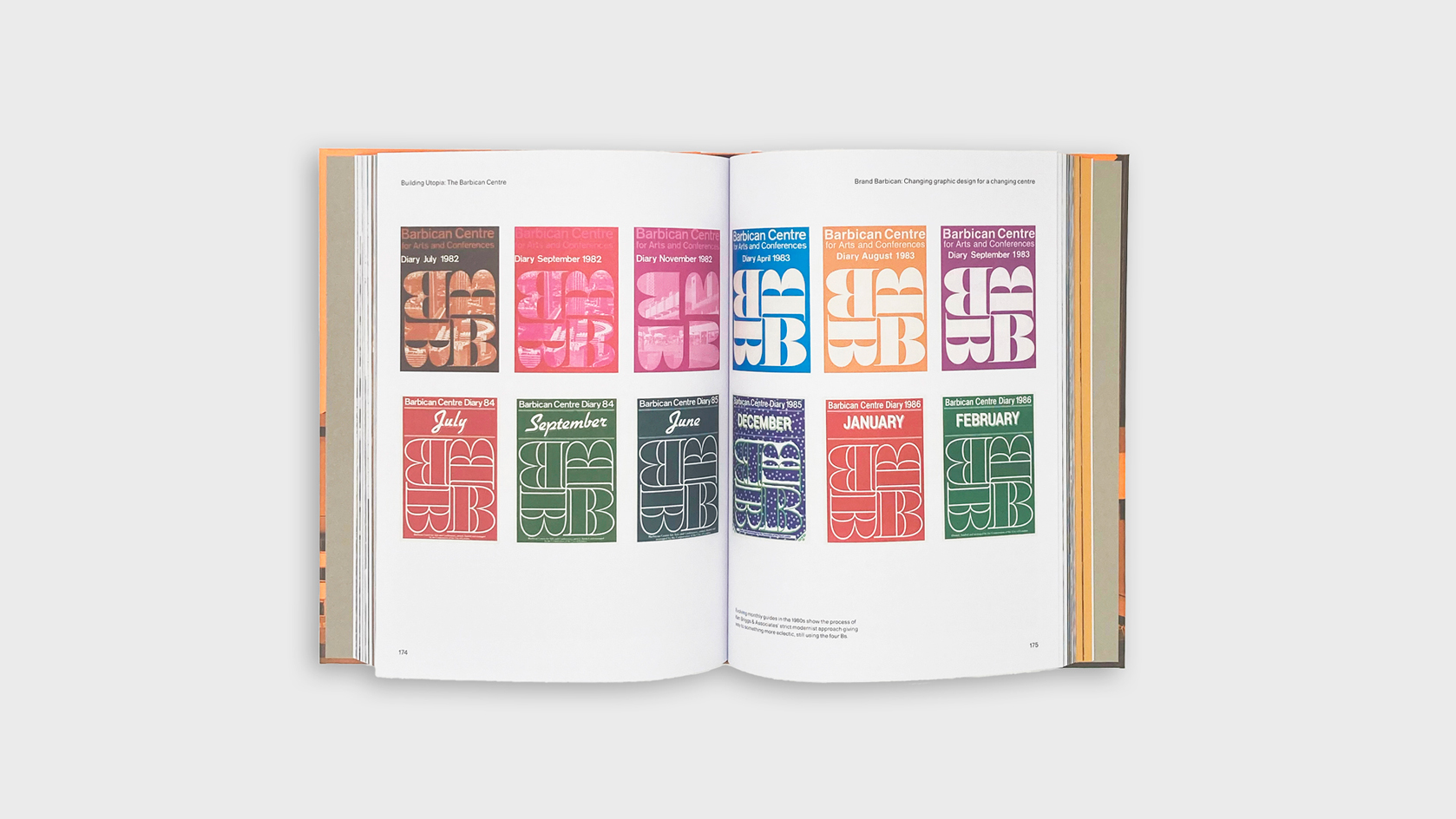

Recent programming designs. Credit: Barbican Archive

The book is bolstered with essays by eminent critics who have lived and breathed the centre’s history and art forms. Cultural historian Robert Hewison reflects on how the centre came into being, and architectural historian Elain Harwood offers a deep dive into the building’s design. Elsewhere, we find Fiona Maddocks on music, Lyn Gardner on theatre, Sukhdev Sandhu on cinema, and Tony Chambers on visual arts.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Chambers, creative director, former Wallpaper* editor-in-chief and self-professed ‘huge Barbican fanboy’, takes readers on a journey through visual arts. He first encountered the building in 1983 on a trip to London for an interview at the Central School of Art. But his love for the place was cemented in 1994 when he rented an apartment in Gilbert House, which he bought in 2000 and still calls home. ‘I was blown away by the modernity and sheer un-Englishness of the arts centre and the surrounding residential estate: it had more in common with the Bauhaus architecture I’d recently been introduced to on my art foundation course in Liverpool,’ his essay recounts.

Chambers takes us through seminal shows, from the inaugural ‘blockbuster’, ‘Aftermath: France 1945 – 55: New Images of Man’ (1982), to epoch-capturing surveys such as photography group show ‘Through The Looking Glass' (1989), and concept-based exhibitions like ‘Seduced: Art and Sex from Antiquity to Now’ (2007).

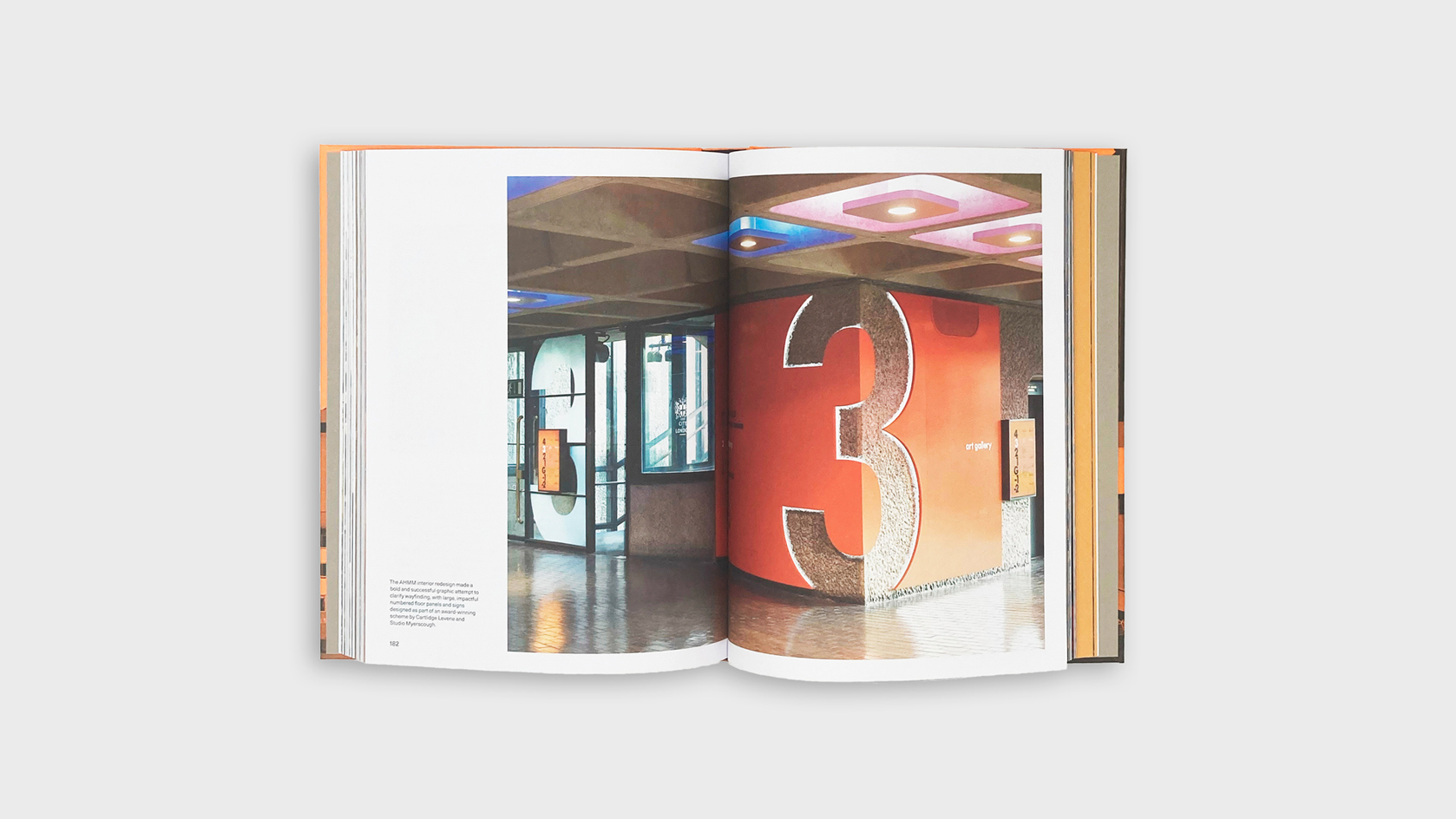

Entrance to art: the gallery ticket desk and design for the opening show in 1982, 'Aftermath'. Credit: Peter Bloomfieldhen

The Barbican Art Gallery has, over the years, developed a knack for anticipating future stars (Grayson Perry exhibited in 2002, a year before he won the Turner Prize); shown an ability to widen its global appeal with commercially orientated shows like ‘The Art of Star Wars’ (2000); and extended its authority not just in fine art, but in the realms of architecture, design and fashion, and everything in between.

Chambers’ essay, and Building Utopia more broadly, highlight the feather-ruffling, intersection-seeking, headline-grabbing role the Barbican Art Gallery has played over the years. A fearless arbiter of art that didn’t always get it right, but earned a rightful place in cultural history. ‘The Barbican Art Gallery at 40 is a remarkable story: of how, despite modest beginnings and a difficult environment, a long line of dedicated curators and directors with brave and imaginative programming have established a world-renowned reputation and identity,’ says Chambers.

In 40 years, the Barbican Centre has proved itself to be not only a building complex, but a cultural microcosm where getting lost and losing yourself are both inevitable.

Few buildings have split opinion to such extremes or made the boundaries between creative disciplines so utterly indistinguishable. It was born as an experimental multi-arts centre, and ended up as a catalyst for all conceivable arts – a creative manifesto made concrete.

INFORMATION

Building Utopia: The Barbican Centre by Nicholas Kenyon (ed) is published by Batsford, £40, batsfordbooks.com

Harriet Lloyd-Smith was the Arts Editor of Wallpaper*, responsible for the art pages across digital and print, including profiles, exhibition reviews, and contemporary art collaborations. She started at Wallpaper* in 2017 and has written for leading contemporary art publications, auction houses and arts charities, and lectured on review writing and art journalism. When she’s not writing about art, she’s making her own.