Time bandit: a new film by artist Steven McInerney takes matter in hand

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

In 1977, the American designers Charles and Ray Eames released Powers of Ten: A Film Dealing with the Relative Size of Things in the Universe and the Effect of Adding Another Zero. The slicked-up version of a more rudimentary prototype released a year prior, the film opened on an aerial view of a picnicking couple on Chicago's waterfront. Shifting ten times further away every ten seconds (the titular ‘power of ten’), the camera first pans up from the pair, working away from the Earth and into the firmament, eventually reaching a distance of 100 million light years from the planet – a coldly blank view encompassing our entire universe.

The shot then reverses, zooming into the man's hand and closing in through increasingly microscopic cells to the very building blocks of life, ending on a multicolour static of atoms at an unfathomable ‘distance’ of 0.00001 ångströms. It's enthralling stuff – linear and mannered in execution but irrefutably psychedelic in practice. It remains simultaneously one of the Eames’ most seminal and outré works.

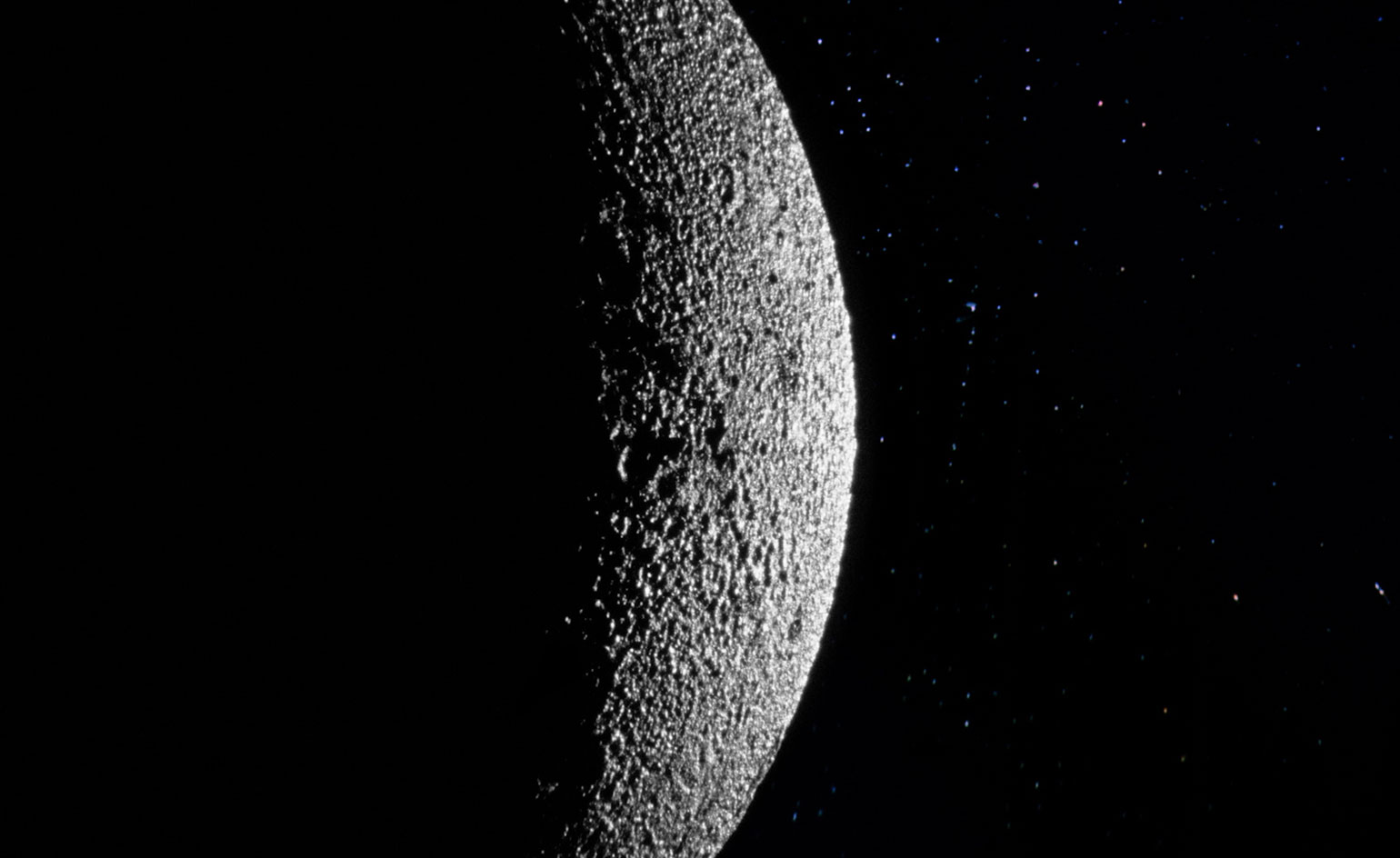

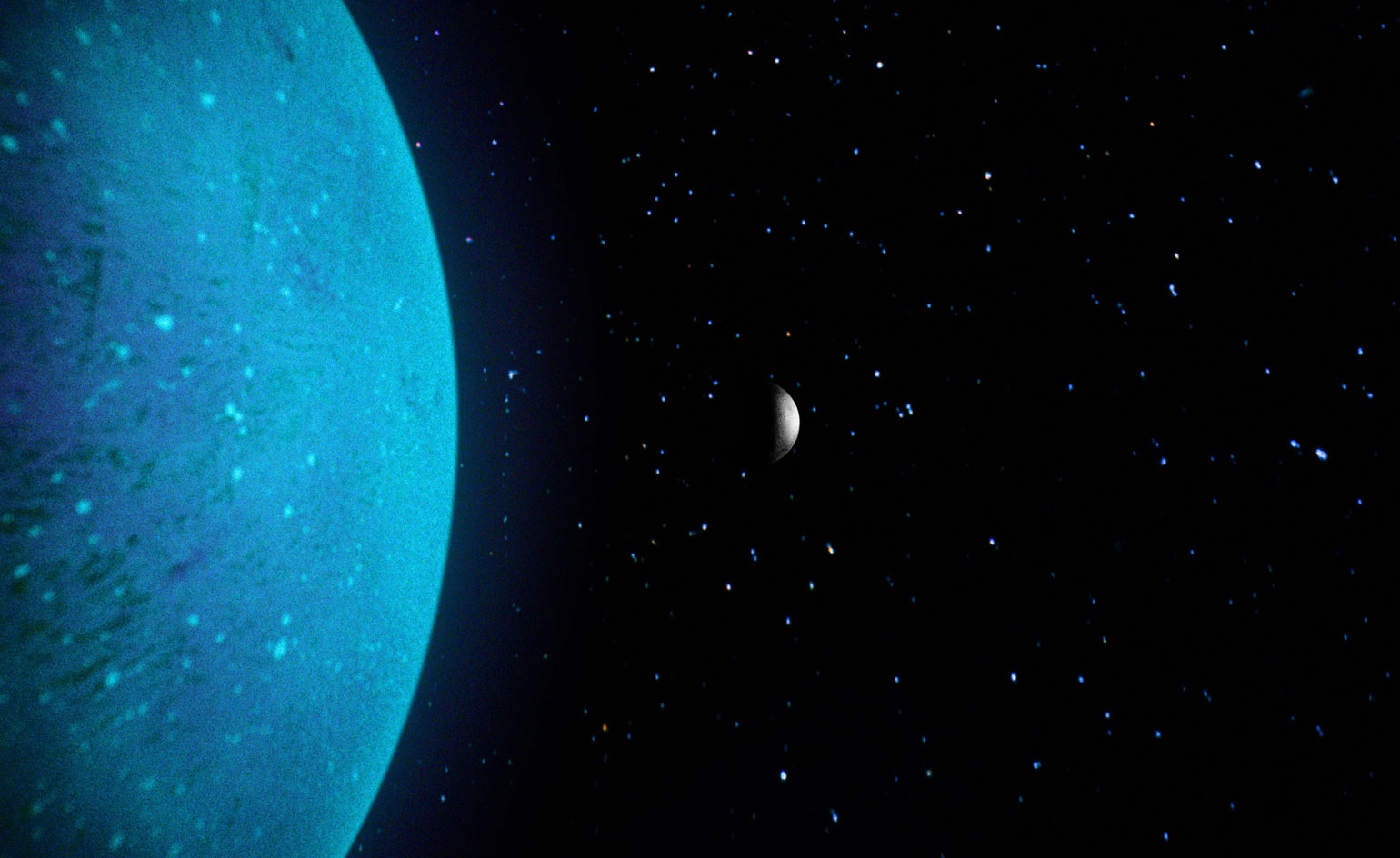

McInerney created his tactile space scenes with models in the studio

A new film by the Australian-born, London-based artist Steven McInerney acts as a kind of successor to Powers of Ten. While not a direct response to the Eames’ piece, A Creak In Time uses it as a jumping-off point, diving headlong into both the freezing depths of the cosmos, and the microcosmic – and luridly colourful – world of cells (chucking in a couple of Sicilian coastlines along the way). It's split into two distinct parts (snappily titled Part 1 and Part 2). ‘Two films,’ McInerney explains, ‘disparate in scale yet connected through the fractal geometry of our physical universe.’

The film – released through McInerney's Psyché Tropes label – is soundtracked by Howlround – a musique concrète duo comprising BBC radio studio manager Robin the Fog and visual artist Chris Weaver, who create otherworldly, abstract drone music from basic found sounds (squeaky gates, the groans of empty stairwells, distant foghorns and so on) manipulated on magnetic tape. ‘This granular process,’ McInerney says, ‘ties in perfectly with the fractal and ever expanding theme of the film, where the macro and the micro coexist, are entangled and only separated by space and time.’

After discovering Howlround's 21012 opus The Ghosts of Bush, McInerney would listen to the duo’s haunting recordings under a sun-dappled window, drifting in and out of consciousness and making notes on the visions he had: ‘Alien landscapes being terraformed by an unseen force on a barren, dune-like planetoid, tiny creatures, beautiful colourful crystals, magnetic fields, quantum chaos, volcanic shorelines, rocks and caverns’. These half-lucid images are A Creak in Time's conceptual ballast.

Certain elements of the film recall Jean Painlevé and Jan Svankmajer

Almost all of the imagery – from brooding views of distant planets to jittery shots of basic organisms and crystal formations – was created by McInerney using in-camera and camera-less techniques (occasionally with purpose-built models), shot on 16mm film over the course of two years.

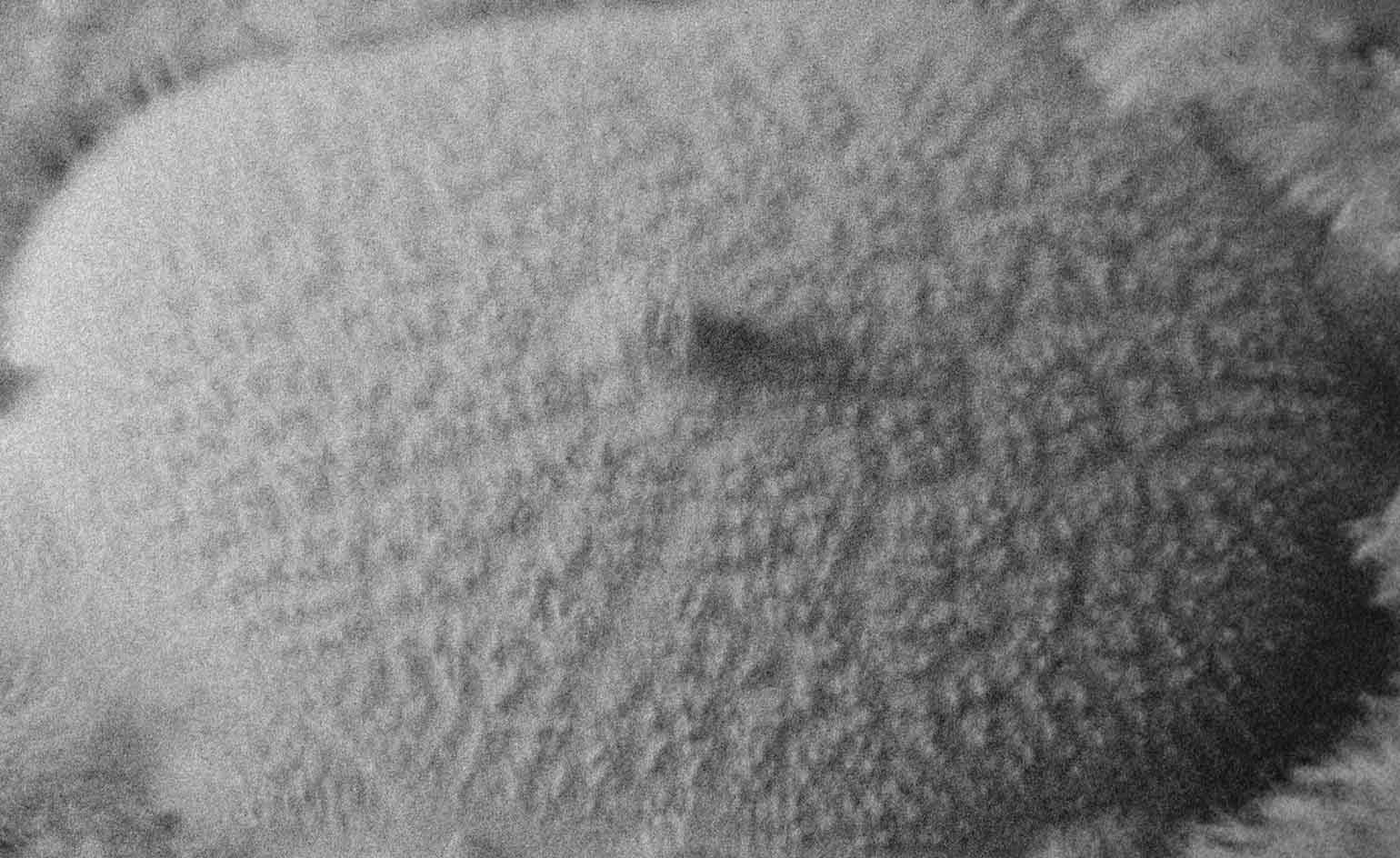

Part 1 in-part comprises colour-skewed views of Siciliy; McInerney's camera pointed directly into the sun in red scale, or on the reverse of half-century old film stock to expose the magneta dyes. The aim of this section, he explains, was to introduce the audience to the cyclical nature of time, unfolding in a natural way on a generically Earth-like stage with a focus on rock formations and water. He was inspired by the abstract, cinematic work of the spiritually-oriented 20th century American filmmaker Jordan Belson. ‘His analogue processes to filmmaking inspired me to take a purist approach to visual effects,’ McInerney explains. The tactile and imposing planets that appear in these sequences were created from balloons and balls hung on fishing wire (very sci-fi DIY); while the terraforming landscapes – brief snatches of fuzzy organic eruptions – were made by resonating an extremely fine lycopodium powder on a Chladni plate placed onto a speaker cone.

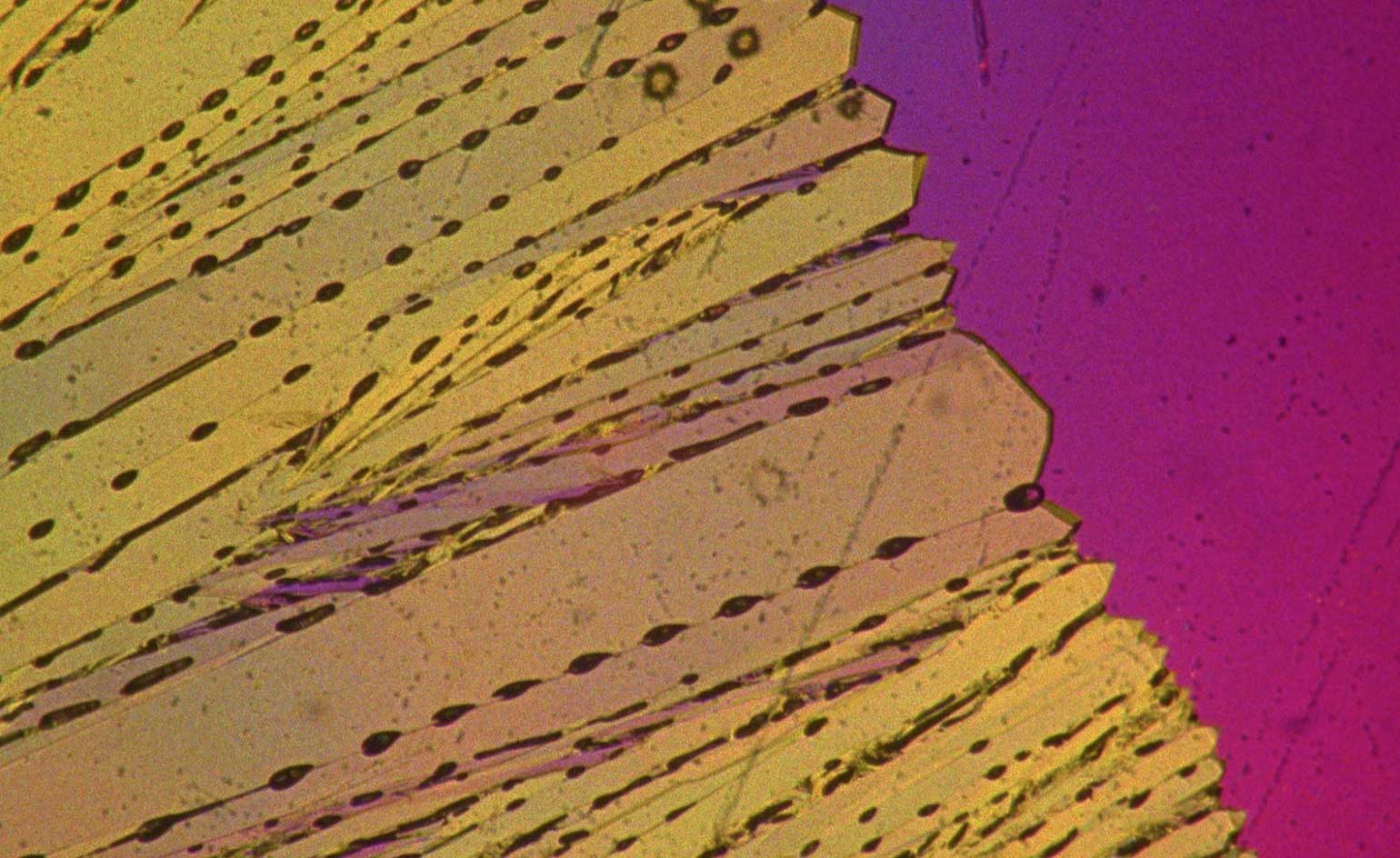

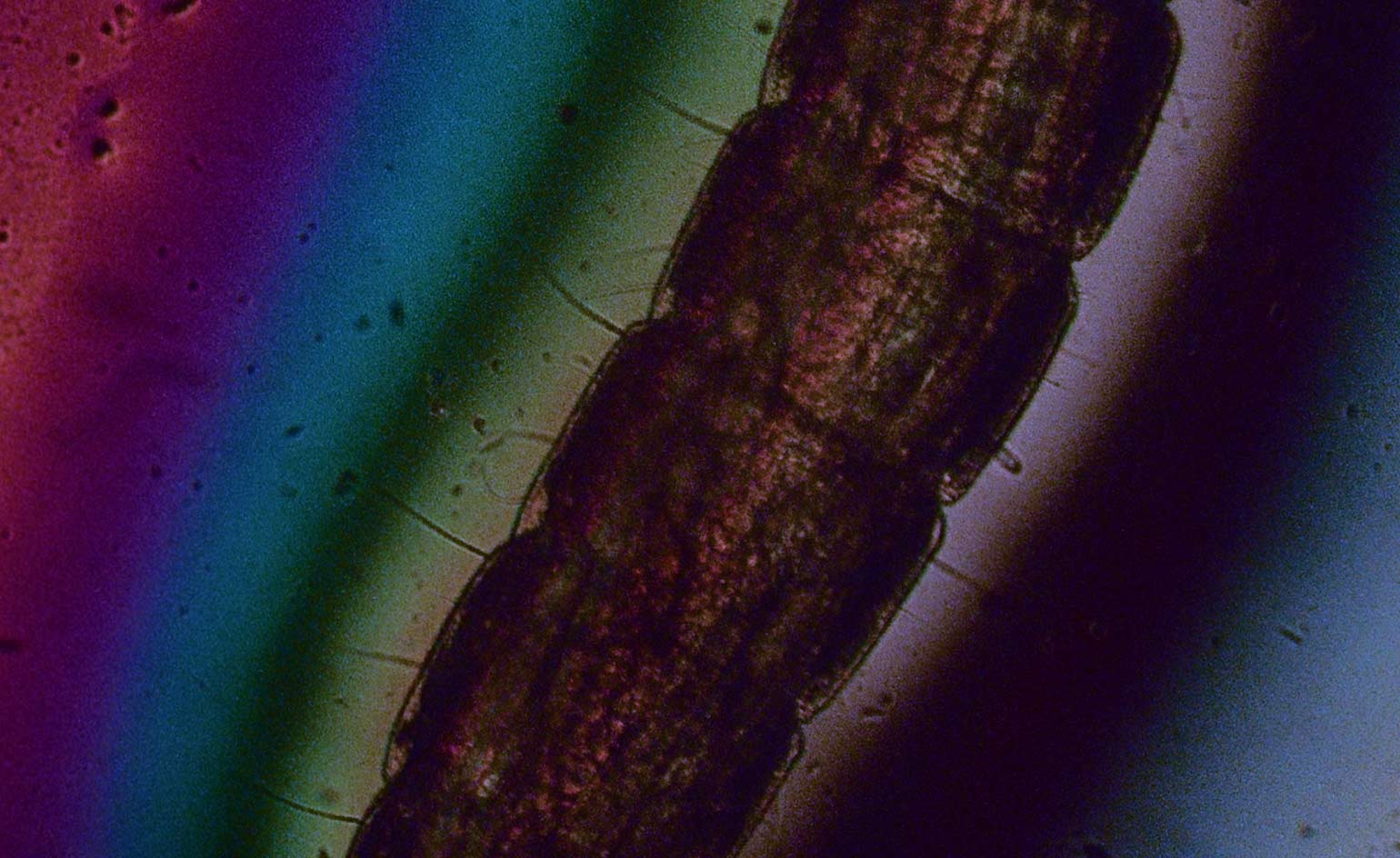

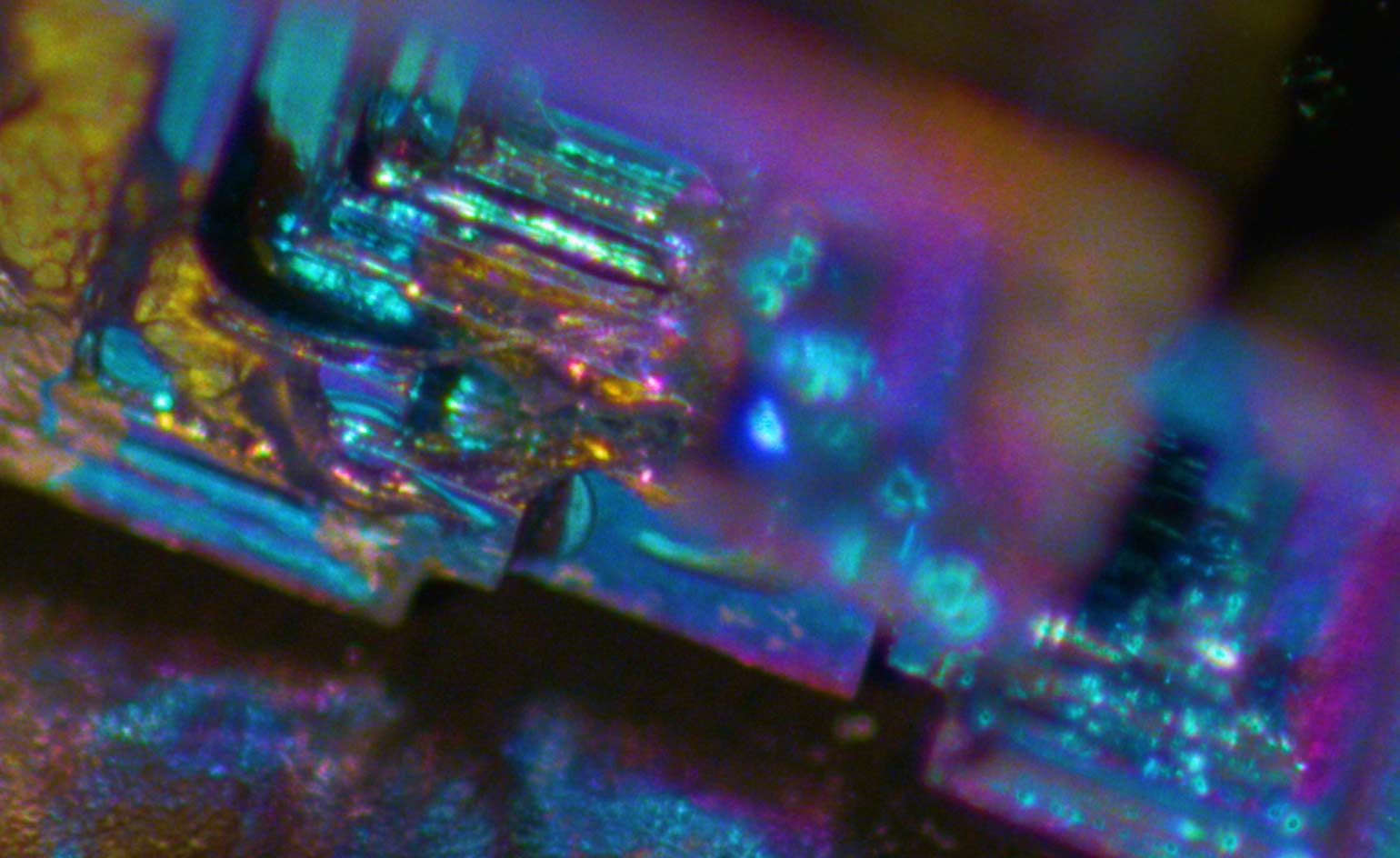

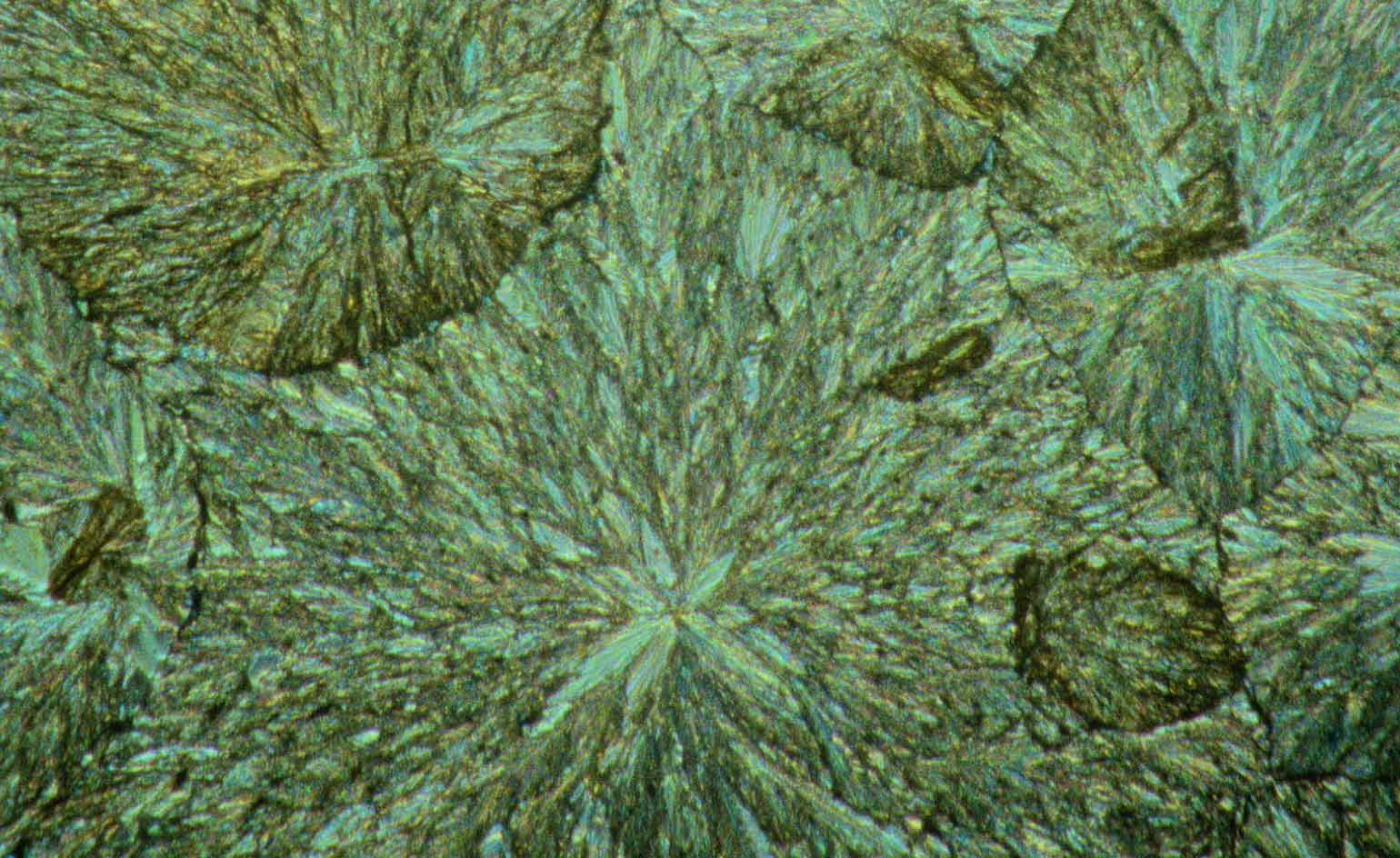

To create the kinetic, multicolour visuals of Part II, McInerney adapted a microscope for his 16mm camera, filming unicellular organism and crystals perishing and dissipating – from seemingly self-generating shards shifting across coloured backgrounds, to tiny insectoid lifeforms arbitrarily sliding around the frame. It was an oddly existential experience for the artist. ‘It was painful to go through this process as these critters portrayed animal like qualities and were full with energy going about their daily business,’ he says. ‘Furthermore, there was the feeling that they were self aware and conscious of my presence and observation, only to survive forever embedded is the layers of celluloid.’

A crystal still from ’A Creak In Time’

This might sound like so much finicky technical fiddling, but the results are startling: 27 narration-free minutes as hallucinatory as they are quietly haunting (in no small part bolstered by Howlround's rhythmic, cyclical wails and groans). It's utterly otherworldly – the lycopodium powder sequences are still perplexing even given McInerney's exposition, recalling the weirdest moments of archaic Jean Painlevé nature documentaries; while the moments of eldritch twig-like bits of matter moving in synchronised, circular movement could have come from the surrealist stop-motion cinema of Czech director Jan Svankmajer (or, perhaps, the Clangers).

As a rumination on both the firmament and the infinitesimal, A Creak in Time is timeless and singular: a cinematic triumph of style and substance.

The film’s first part features a host of familiar, but otherworldly vistas (captured in Sicily).

A surreal terraforming landscape was made by vibrating fine powder on a speaker.

McInerney’s microscopic filming techniques are both cinematic and psychedelic in practice.

While not a direct response, the film nods to the Eames’ 1977 masterpiece Powers of Ten.

McInerney filmed both crystal formations and single-cell organisms for the work.

The film’s visuals also recall historic science and nature documentaries.

McInerney working in the studio

INFORMATION

For more information, visit the Psyché Tropes website

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Tom Howells is a London-based food journalist and editor. He’s written for Vogue, Waitrose Food, the Financial Times, The Fence, World of Interiors, Time Out and The Guardian, among others. His new book, An Opinionated Guide to London Wine, will be published by Hoxton Mini Press later this year.