Pavilion 13 is a brutalist architecture landmark, reborn as a 21st-century Ukrainian cultural hub

Kyiv studio ФОРМА restored Pavilion 13 into a new contemporary art centre for Ukraine; they tell us the story behind the project

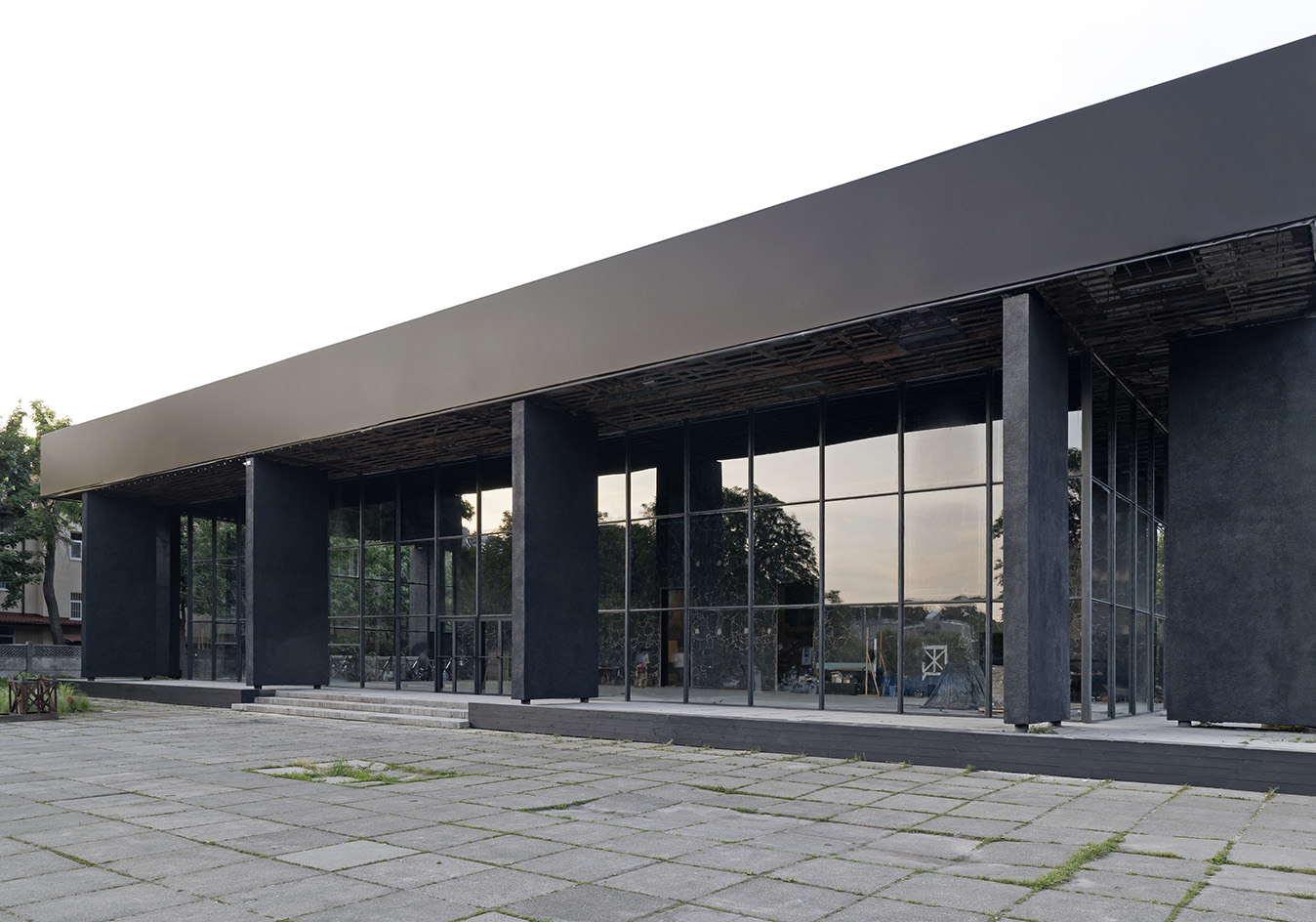

Pavilion 13 in Kyiv, Ukraine, a Soviet brutalist-architecture-era exhibition hall originally designed by SS Pavlovsky, has just been renovated into a contemporary art centre. The project, led by ФОРМА architects and commissioned by RIBBON International, not only brings a modernist architecture gem back to life, but also offers an important cultural space for creatives and art enthusiasts in the Ukrainian capital at a challenging time for the country, with the war with Russia ongoing.

Lead architects Iryna Miroshnykova and Oleksii Petrov worked on the scheme, which opened this summer (2025), hosting artist Sam Lewitt, who presents his project, Шубін (SHUBIN), on site. We caught up with ФОРМА to find out more about the building and the practice’s journey.

Tour Pavilion 13, Ukraine's new art hub, with its architects, ФОРМА

Wallpaper*: Tell us more about Pavilion 13 and its significance.

ФОРМА: Pavilion 13 was built in 1967 in Kyiv as part of a large exhibition complex that brought together architecture, industry, and educational functions, promoting various industrial achievements – from horticulture to transportation. Pavilion 13 was originally dedicated to the coal industry and reflected the important role of mining in the economic and regional development of the country, particularly in the eastern regions of Ukraine.

Its value today lies not only in the subject it once represented, but also in how that subject was expressed architecturally. The simplicity of modernist geometry combined with inventive detailing captures a specific moment in the evolution of public exhibition spaces. It is a building that holds memory, while also offering space for reinterpretation. Through its renewal, we are not seeking to rewrite its history, but rather to offer it a 'future continuous'.

‘Once an immersive exhibition feature, a lower level now functions as a bomb shelter. At the same time, we see it as a vital part of the pavilion’s architectural and cultural legacy’

ФОРМА

W*: What about the building’s make-up?

ФОРМА: Internally, the pavilion is loosely divided into several functional zones. The central part is a large hall with a glass façade, serving as the main space for events, exhibitions, and performative formats.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

There is also a preserved 'cinema hall' – a space that historically hosted film screenings and public events. While the original seating was lost, the projector room remains intact and holds potential for new forms of use.

A distinctive feature of the building is the hall with a sloped ramp leading to the underground level, where the original model of a coal mine still exists. Once an immersive exhibition feature, this lower level now functions as a bomb shelter. At the same time, we see it as a vital part of the pavilion’s architectural and cultural legacy – a space with potential for future archival or curatorial interventions.

In addition, there’s a flexible-use hall that can be adapted for different formats – from exhibitions and discussions to screenings or temporary installations.

The recent adaptation included the restoration of basic infrastructure: updated utility systems, new flooring, improved lighting, inclusive restrooms, and spaces suitable for temporary architectural or artistic interventions. The pavilion remains as open and adaptable as possible – without rigid zoning – so it can respond to the evolving needs of its programmes and users.

Lastly, it’s worth mentioning the orchard behind the pavilion – a small apple grove with old trees that still bear fruit. Every autumn, the ground is strewn with apples. We’ve recently enriched this ecosystem with additional plants to enhance the landscape, and expect the garden to renew itself seasonally in the coming year – becoming another site of interaction between natural and built environments.

W*: Every project has its challenges. What were yours in this renovation?

ФОРМА: Each stage of the renovation process brought challenges, which is only natural when working with a structure that had stood neglected for many years. The main difficulties weren’t architectural, but infrastructural: severely deteriorated utility systems, damage from moisture, and undocumented alterations made in previous decades. But perhaps the most difficult challenge was striking a balance between restoration and preservation.

We chose a phased approach – gradual, respectful of the existing materials. It takes more time, but allows for informed decisions that respond to the building’s real condition and historical layers.

‘Heritage isn’t always about grand narratives – often, it resides in subtle, overlooked details that ask for care, patience, and close observation’

ФОРМА

W*: What excited you about working on the project? What surprised you?

ФОРМА: One of the most surprising discoveries was the central wall of the main hall. Beneath layers of white paint, we uncovered an experimental decorative surface made from black broken glass fragments – a technique that was once widespread, yet uniquely interpreted in each instance. It turned out to be more than an aesthetic detail: it spoke to the original designers’ resourcefulness and attention to material, working creatively within the constraints of their time and speaking about 'coal' directly.

Findings like this remind us that heritage isn’t always about grand narratives – often, it resides in subtle, overlooked details that ask for care, patience, and close observation.

Ellie Stathaki is the Architecture & Environment Director at Wallpaper*. She trained as an architect at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece and studied architectural history at the Bartlett in London. Now an established journalist, she has been a member of the Wallpaper* team since 2006, visiting buildings across the globe and interviewing leading architects such as Tadao Ando and Rem Koolhaas. Ellie has also taken part in judging panels, moderated events, curated shows and contributed in books, such as The Contemporary House (Thames & Hudson, 2018), Glenn Sestig Architecture Diary (2020) and House London (2022).

-

Making mirrors with A Vibe Called Tech, the collective democratising design

Making mirrors with A Vibe Called Tech, the collective democratising designLast week, Wallpaper* Paris Editor Amy Serafin spent a day with a group of creatives led by Julie Richoz, making mirrors: here's what went down (and how to make your own)

-

A postcard from We Design Beirut: 'We’re learning how to break barriers and create dialogue'

A postcard from We Design Beirut: 'We’re learning how to break barriers and create dialogue'The second edition of We Design Beirut celebrated design, architecture, heritage and creativity

-

Inside the Centre Pompidou's last hoorah

Inside the Centre Pompidou's last hoorahAfter shutting its doors for five years of renovations, French record label Because Music saw the empty site as the perfect space for its 20th anniversary celebrations

-

The Architecture Edit: Wallpaper’s houses of the month

The Architecture Edit: Wallpaper’s houses of the monthWallpaper* has spotlighted an array of remarkable architecture in the past month – from a pink desert home to structures that appears to float above the ground. These are the houses and buildings that most captured our attention in August 2025

-

Ukrainian Modernism: a timely but bittersweet survey of the country’s best modern buildings

Ukrainian Modernism: a timely but bittersweet survey of the country’s best modern buildingsNew book ‘Ukrainian Modernism’ captures the country's vanishing modernist architecture, besieged by bombs, big business and the desire for a break with the past

-

Soviet brutalist architecture: beyond the genre's striking image

Soviet brutalist architecture: beyond the genre's striking imageSoviet brutalist architecture offers eye-catching imagery; we delve into the genre’s daring concepts and look beyond its buildings’ photogenic richness

-

Meet the 2024 Royal Academy Dorfman Prize winner: Livyj Bereh from Ukraine

Meet the 2024 Royal Academy Dorfman Prize winner: Livyj Bereh from UkraineThe 2024 Royal Academy Dorfman Prize winner has been crowned: congratulations to architecture collective Livyj Bereh from Ukraine, praised for its rebuilding efforts during the ongoing war in the country