Under pressure: Apple applies skill, science and true grit to get the most out of its electronics

Apple’s Cork HQ is home to a sophisticated R&D lab. Wallpaper* took a tour behind the scenes to see how longevity is baked in to new products

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

In 1980, an up and coming young tech mogul named Steve Jobs, high on the success of the Apple II personal computer designed by his company co-founder Steve Wozniak, found himself drawn to Ireland. The lure was financial, thanks to generous tax breaks on offer from a government determined to harness Ireland to the silicon revolution. Forty-five years later, Apple is the largest employer in Cork, and the original team of 60 has expanded to 6,000. The company’s Irish division is the country’s largest company, with a complex and ever-evolving web of incentives that keep the Cork campus at the heart of Apple’s global operation.

Ongoing works at Apple's Cork campus

So what actually happens on this modest-looking industrial estate in Holyhill, just a couple of miles west of the city centre? Wallpaper* joined a small group of international tech media being ushered around this hilltop campus of steel-clad and glass-louvered offices, with its far-reaching views to the rolling green hills of Co Cork. Currently in the process of another round of expansion, Apple’s operations here are wide-ranging, from Apple Care support through to administration, as well as a substantial complex of laboratories dedicated to a core element of the company’s ethos; testing and quality assurance.

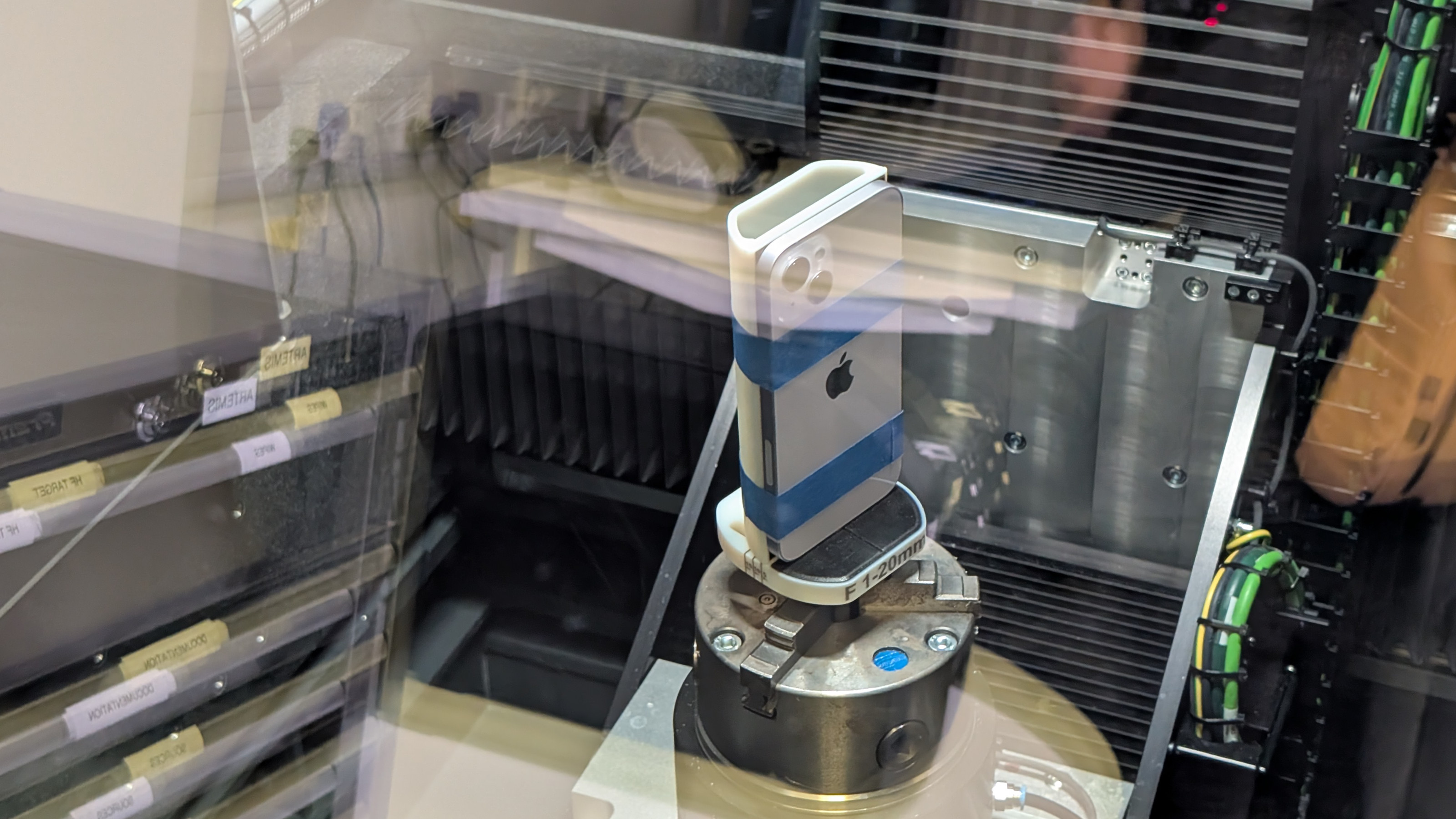

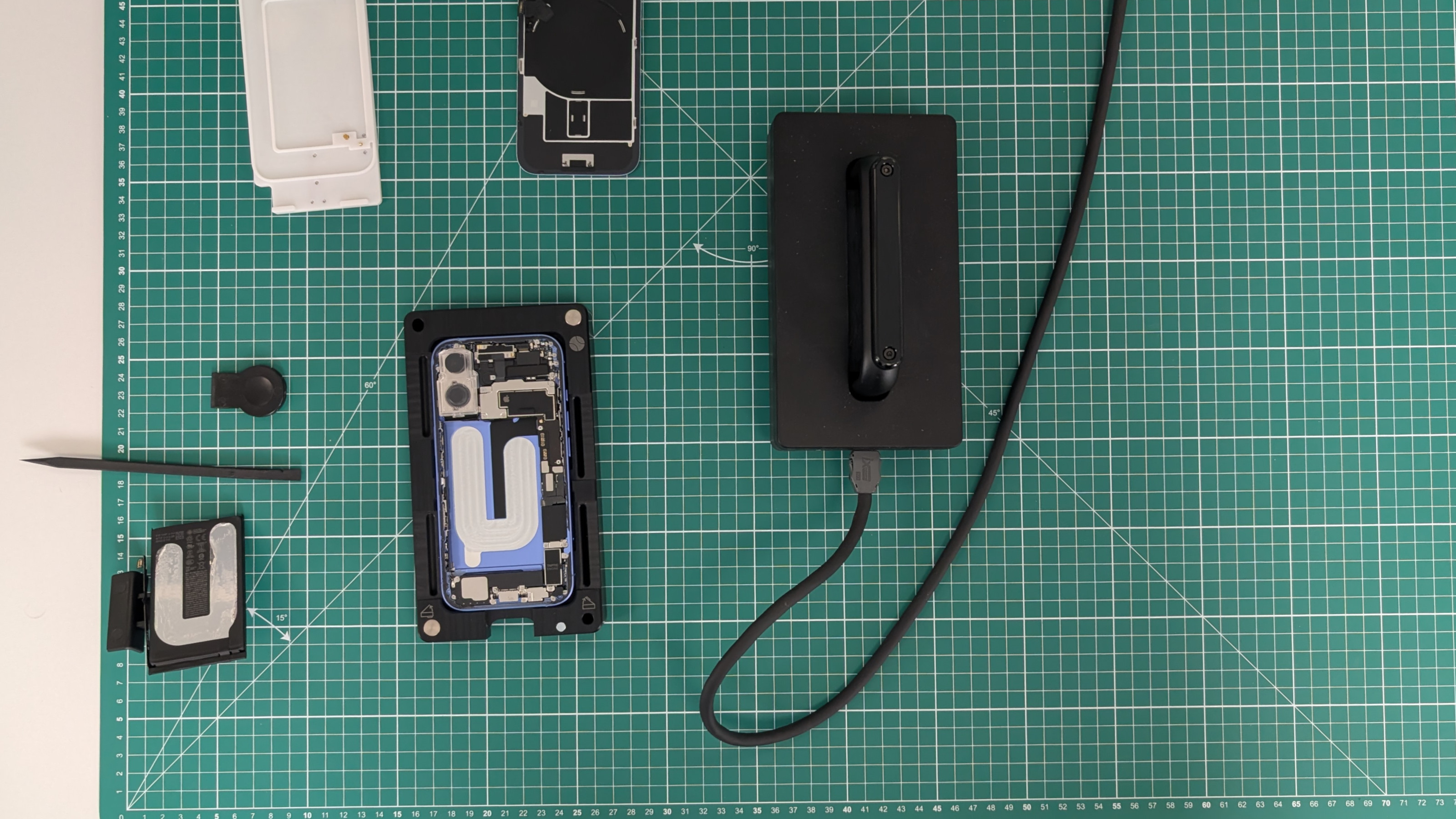

Ready for a close-up: an iPhone gets scanned

We’re here to experience the lengths to which Apple goes to ensure its products work consistently and efficiently, a magical mystery tour into the inner workings of a famously secretive company. That’s not to say that any secrets will be revealed. Instead, what’s uncovered is a set of meticulously choreographed demonstrations to support the company’s stated ‘commitment to achieving carbon neutrality for our entire carbon footprint, including transitioning our entire value chain to 100 percent clean electricity.’

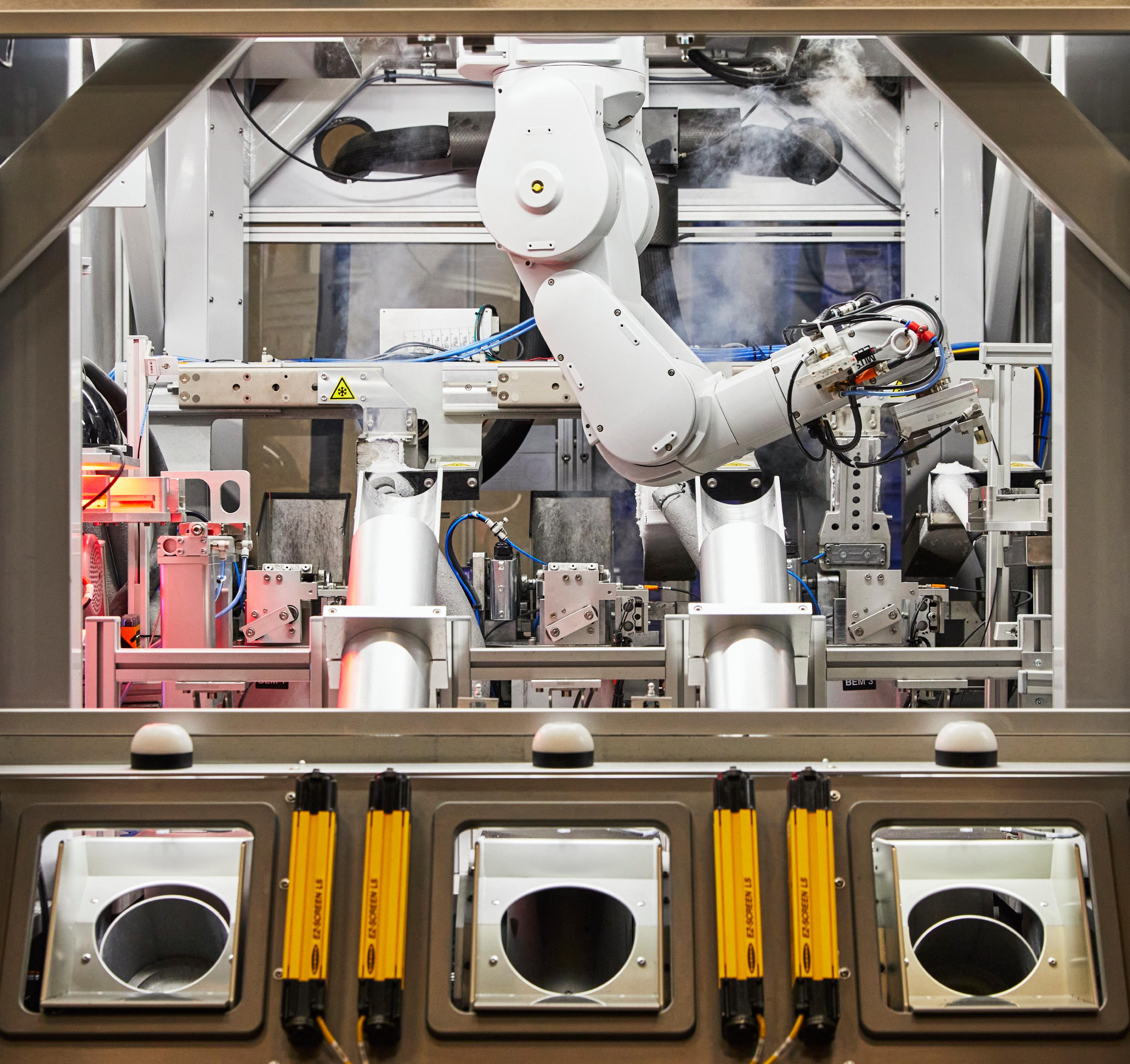

Shake and bake: Apple's testing facility in Cork

It's a bold move, a commitment buffeted every which way by doubters and environmental naysayers, the shifting sands of the global market and the near infinite complexity of supply chain management. However, if anyone can do this, Apple can. Only a company with god-mode levels of control, influence and wealth can possibly make the changes that can move the dial, shifting entire economies in the process and changing things for the better for everyone else. In the first of what’ll be countless talks and demonstrations in a series of brightly lit but daylight-free rooms, we’re talked through what underpins this commitment, what’s needed and what’s already happened, as well as Apple’s renewed commitment to what it calls Longevity, by Design.

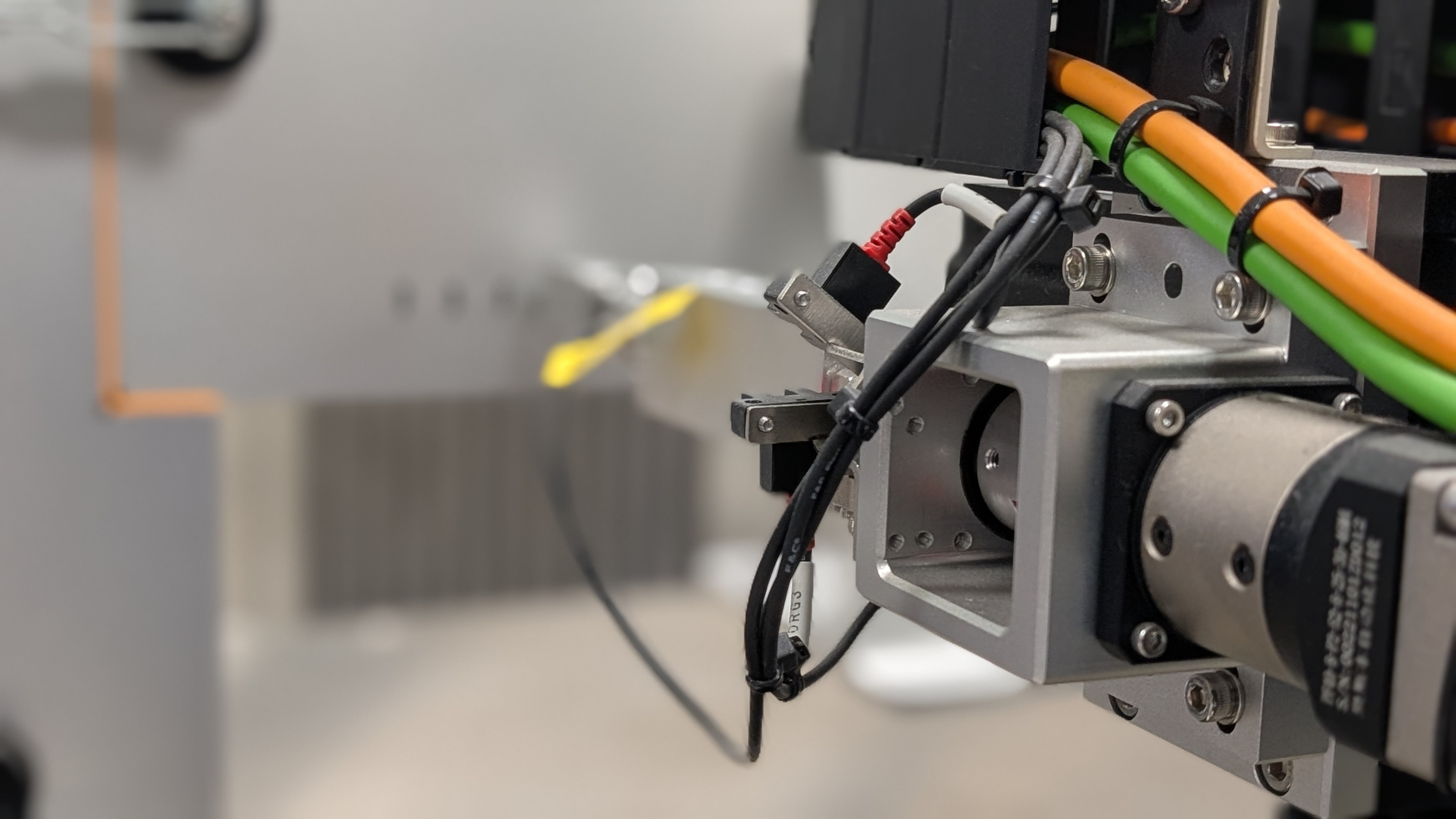

Inserting a USB cable, over and over and over again

It's no exaggeration to say that an iPhone represents a substantial investment for the customer, a premium device that has, since its introduction in 2007, sold nearly 2.5 billion units. The original phone only had one repairable component, the Sim card slot. These days the device is more repairable – and recyclable – than ever before. Add in levels of durability that far outstrip the comparatively fragile early models, and you have something that retains its value for many years (far more so than its competitors). Apple knows that 100s of millions of 5+ year old iPhones are still in use. To better improve that all-important carbon footprint, that number needs to rise still further.

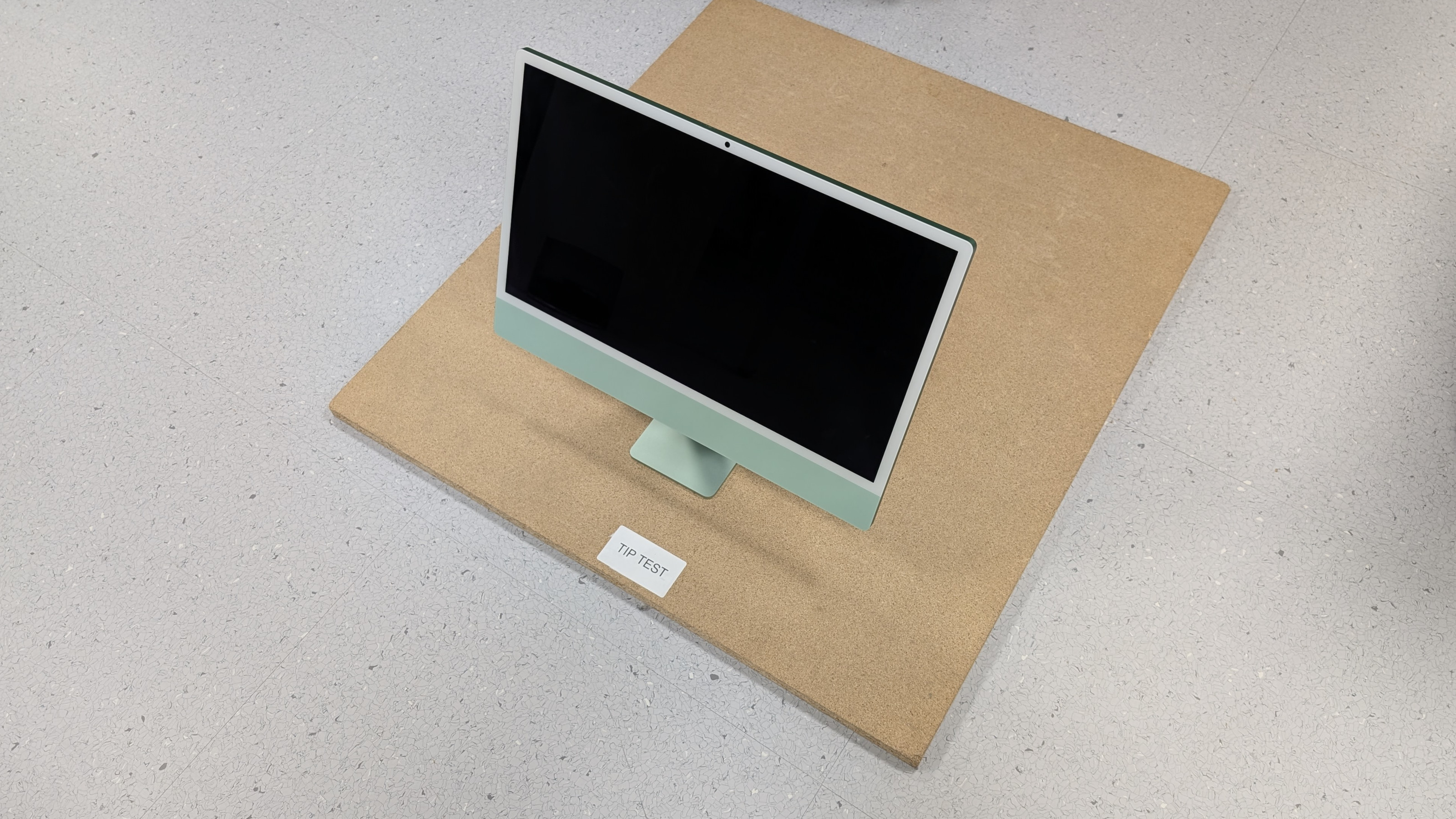

An Apple iMac gets the swivel test

Tom Marieb, Apple’s Vice President of Product Integrity, talked us through the company’s work in this sphere, emphasising that longevity is a ‘win win’ for the company. Three pillars – reliability, software support and repair – are considered essential if the iPhone is to become a truly carbon neutral product. To get to this point, Apple not only has to design products with lower carbon intensity, ramp up its use of renewables and avoid direct emissions wherever possible.

A device that mimics fingers prodding endlessly at a touch screen

To this end, the company’s offices, data centres, and labs already run on renewables. The most challenging task lies in decarbonising manufacturing. Again, the best option is to switch suppliers over to renewable energy sources but that’s not always straightforward in every market and requires a whole new level of geopolitical machinations. Then there’s the fact that some suppliers also manufacture for other brands and might not be contractually bound to adhere to Apple’s level of requirements for their entire output.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Testing the iMac

It's a minefield. Speaking of which, another fraught component of modern electronics manufacturing is sourcing the raw materials themselves. Currently, Apple reckons that recycled materials make up just under a quarter of a device’s total components, some devices more than others. Some key materials, notably cobalt, tin, gold and rare earths, are already 99% recycled. The latest MacBook Air contains 55% recycled content, most notably the aluminium casing, which is 100% recycled.

A 3D scan of an iPhone 14

It's a day of facts and statistics. Back in 2015, aluminium components made up around 27% of the carbon footprint of an Apple device. By 2024, aluminium accounted for 7%. Packaging has switched almost entirely to 100% fibre-based packaging – only 1% of all Apple packaging still consists of plastics. Change is possible. It’s just not always very sexy, dynamic or exciting.

Apple attempted to shift this perception with its introduction of the Daisy ‘de-manufacturing’ machine, a specialised robot that can break down the intricately assembled and bonded jigsaw that is an iPhone. Yet there are just two Daisies in operation, alongside a few other more specialised de-manufacturing machines, one in Europe and one in the US. Between them they can disassemble up to 2.4 million iPhones a year (or 0.1% of the iPhones ever made).

Apple Daisy de-manufacturing robot

We’re not told, but it wouldn’t be surprising to find that this maximum limit isn’t being reached. Apple simply isn’t getting as many old devices back as it should – most of them are lurking in drawers, immobile and unused. This clearly doesn’t help anyone; as one presentation points out, to match 1 metric ton of recovered and recycled materials you’d need to extract 2,000 tons of rock from the ground.

Raw material extracted by Daisy

In testing circumstances: into the labs

Presentations over, it’s time to visit the labs. A short walk down the hill from the main campus, hidden in a non-descript brick and ribbed metal shed, this testing facility is mirrored by around 100 other labs around the world. All share their results and often work simultaneously across new products, looking to replicate and reproduce, confirm and collaborate results in true scientific fashion. For the purposes of Wallpaper*’s visit, there’s an element of what one might call ‘sustainability theatre’, with a number of carefully staged tests hinting at what happens en masse while the real work is presumably carried on elsewhere.

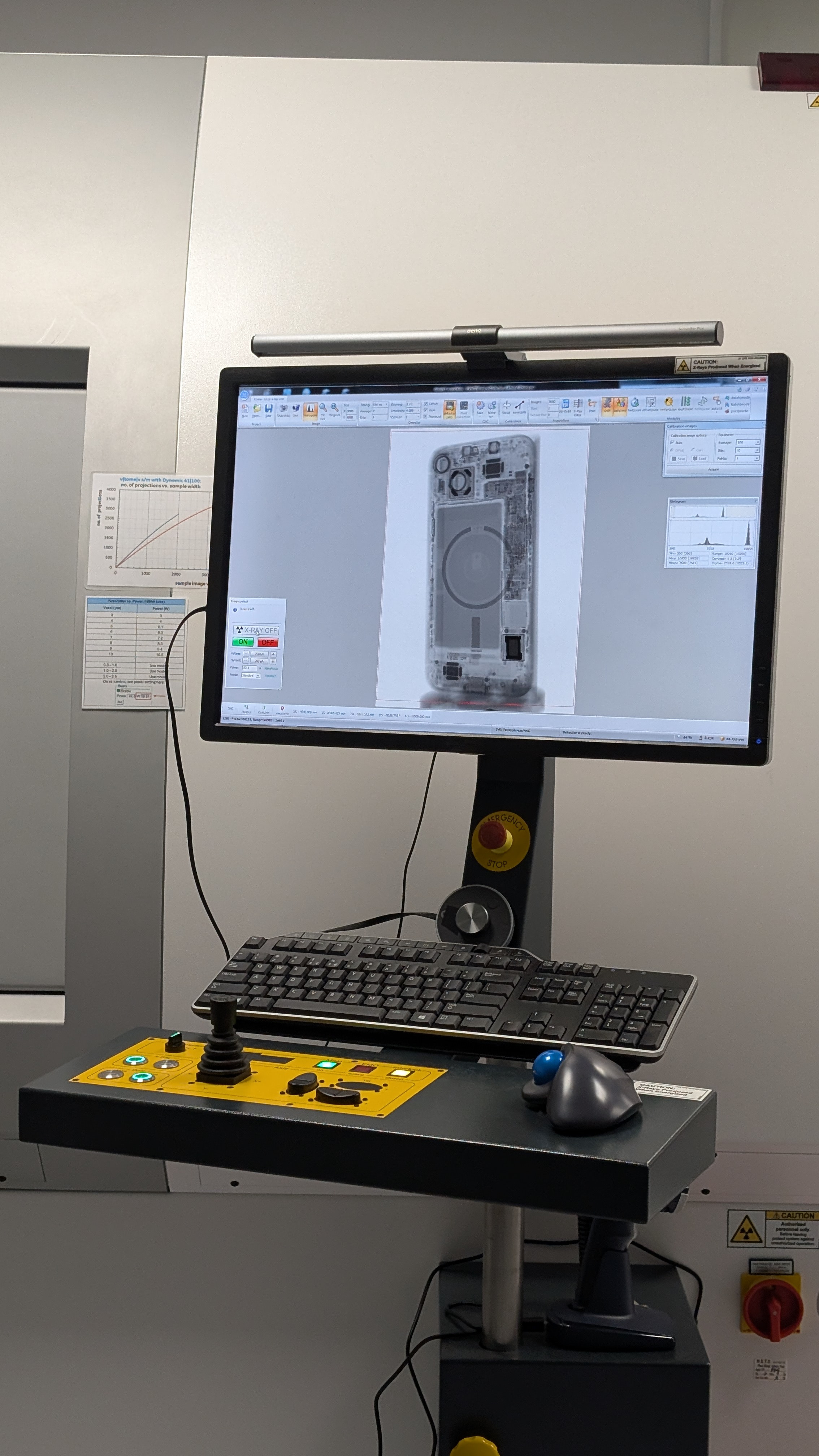

AirPods getting CT scanned

For a device like the iPhone, around 10,000 production-ready units are put through a battery of tests, ranging from radiation, extremes of temperature, mass, force and impact. Specialist rigs are set up to conduct Sisyphean levels of swiping and prodding, folding and switching, shaking and vibrating. Vast ovens and freezers bake and chill components to evoke summer heatwaves, aircraft holds and Arctic research centres.

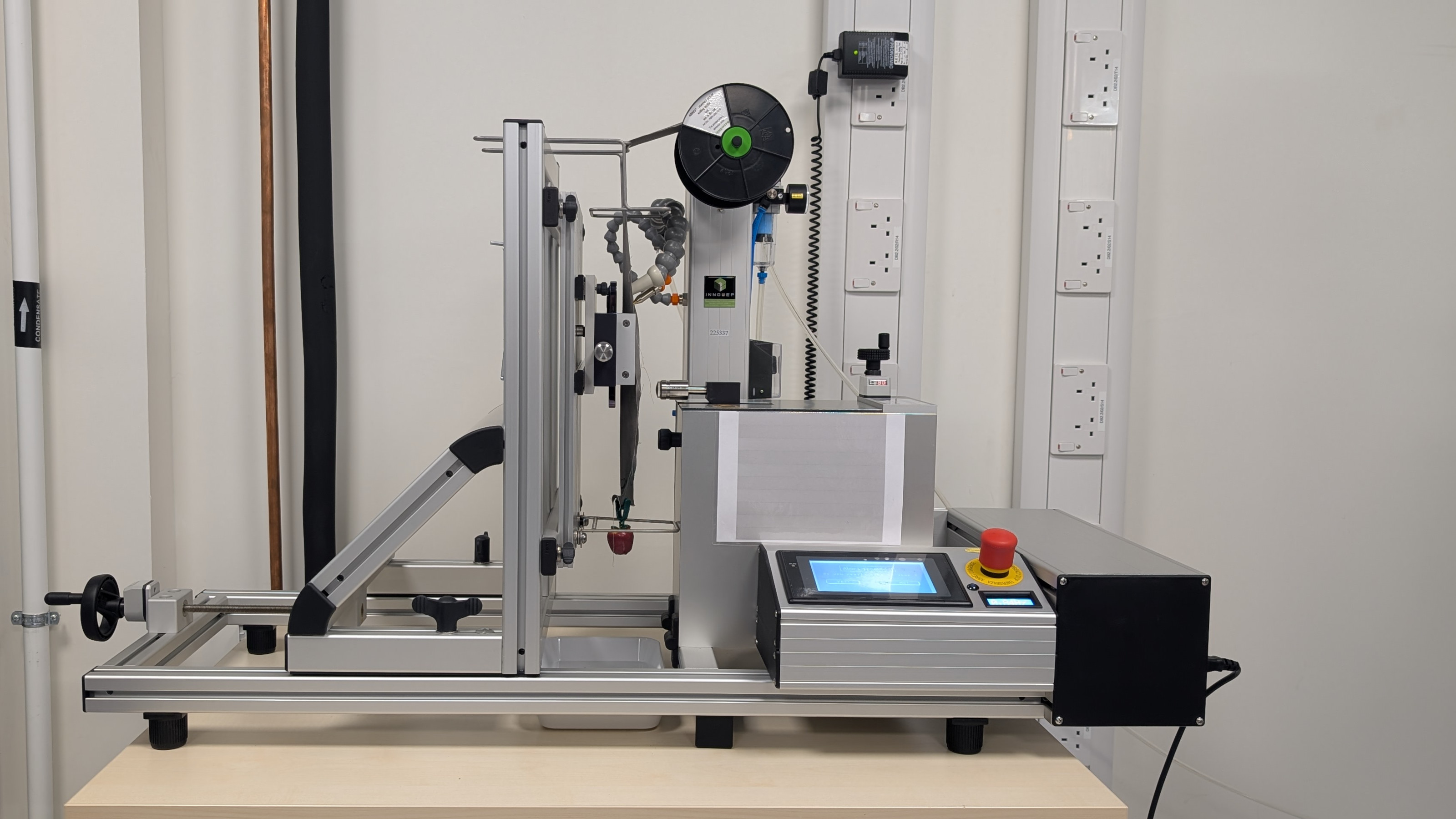

The sandstorm in a box (the windscreen wiper clears the screen to see inside)

A sandstorm in a box fills every nook and cranny of your Apple product with clouds of irritating, abrasive grains, whilst a bench test gently folds and pushes a screen back and forth on its hinge over and over again. In amongst all this carefully set up test gear is a piece of old-fashioned hardware abuse – a tip test that simply requires a (gloved) hand to push over a monitor, hard. Our tour of tech media leapt at the chance.

Give it a shove: the iMac tip test

All this is essential. A reputation for quality doesn’t come out of nowhere and Apple stakes its reputation – and prices – on creating premium hardware that can withstand whatever life can throw at it. We’re shown a new technique devised to de-bond a battery from an iPhone, part of the Self Service Repair network of machines that can be rented to breathe new life into your device. All this takes place in room after room, located off of maze of Severance-like corridors (the reference came from the Apple team itself), each identified only by gnomic codes with access granted to a lucky few.

Displays are given the salt water treatment

There’s not a lot to see in this alchemical wizardry of battery debonding. No ceremony, no fuss, nothing special. Yet the fact that such a supposedly simple operation is hailed as a remarkable piece of magic after no less that 16 generations of the project is revealing. What does it reveal? That technology – and not just Apple’s technology – has spent decades going the wrong direction in terms of sustainability. Our devices have only achieved the levels of sophistication we all take for granted by avoiding the ability to swap out a battery or replace a single component. Condensed, compacted, integrated, completely impenetrable to the layperson, innovation and complexity are inseparable and intertwined.

De-bonding an iPhone battery in under a minute

Like other manufacturing behemoths like IKEA or Stellantis, Apple makes big decisions that have a substantial, immediate impact. When Apple made the decision to take control of its own silicon destiny at the turn of this decade, it also gave itself the ability to cascade change right down the supply chain. It also highlighted the need to be seriously and deeply conversant with detail on an atomic level.

A scan of an iPhone at Apple's Applied Research Labs

The company’s Applied Research Labs can scan and scour any device, from 3D CT scans that tunnel through the solids and voids of an object down to electron microscopes that take wafer thin slices of silicon and scan their surface down to the micron. This is the forensic world of materials science, where nanometre-sized defects can be traced and solved. Extraordinary products require extraordinary technology to build, dissemble and decode, and Apple has demonstrated that it’s got the lot.

Cold room: iMacs are subjected to freezing temperatures

An interview with Tom Marieb, Apple Vice President of Product Integrity

When Wallpaper* talks to Tom Marieb about what we’ve seen and what it means, the feeling is that the heavy lifting takes place behind the scenes, out of sight and mind of the consumer. Marieb stresses that ‘the key thing for us is that they’re in use,’ when it comes to old iPhones. Could a phone ever be considered more valuable as scrap than as a functioning device? Marieb doesn’t have the figures to hand but assumes it’s a substantial period of time.

Cold room: iMacs are subjected to freezing temperatures

‘We really strive and look at every feature and how much battery it uses,’ he says, ‘we support whatever software upgrade the hardware can handle.’ In a world of increased longevity, how do early adopters fit in? Surely people who want the latest and greatest the minute it’s available are taking the least sustainable path. Or do they function as essential ambassadors for the Apple experience? ‘It’s our job to make the technology people want to get if they’re early adopters,’ Marieb explains, adding that Apple has increased its focus on Trade In in recent years. ‘Our worst case is when people take [devices] out of use.’

A CT scan of a pair of AirPods

The new R&AD focused engineering and test lab in Cork only opened in 2022, bringing this kind of work to Europe for the first time. Together with Apple’s 2030 commitments, the Longevity, By Design program is making huge strides in the way in which we perceive, use and dispose of electronics, from AirPods to a Studio Display.

None of this can sate the innate desire to upgrade, however much effort Apple puts in to making things last longer and work better. As Tom Marieb explains, ‘it’s our goal to make it easy for the customer to do the right thing. We want to be the ones that worry. And believe me, we have a lot of people to do that worrying.’

As close as we got to the iPhone 17. Allegedly

Jonathan Bell has written for Wallpaper* magazine since 1999, covering everything from architecture and transport design to books, tech and graphic design. He is now the magazine’s Transport and Technology Editor. Jonathan has written and edited 15 books, including Concept Car Design, 21st Century House, and The New Modern House. He is also the host of Wallpaper’s first podcast.