Radicals and ravers: C.P. Company celebrates its sartorial style makers

As the Bologna-founded brand celebrates its 50th anniversary, C.P. Company president Lorenzo Osti takes Wallpaper* back to the beginnings of the boundary-pushing label and its evolving adopters

‘I have to tell you about Bologna,’ says Lorenzo Osti, president of C.P. Company, the brand founded by his father Massimo Osti in 1971 (it was first called Chester Perry, then C.P. Company from 1978). As his cat crawls over his computer during our video call and he cracks open a window to let out the mid-summer Italian heat, lively Lorenzo takes me back to the beginnings of the legendary brand.

‘Bologna is the red one – for the colour of the roofs, but also for its political reputation. Our city has never been run by a [politically] right party since the Second World War. Never. We were Communist, and now we have a democratic party. All of the city are proud of that. The social aspect is very relevant here.'

As C.P. Company turns 50, menswear lovers continue to obsess over its iconic pieces, like the Explorer, Goggle and Metropolis jackets, while its fiercely loyal fanbase revels in the almost mythological connection to Milan’s paninaro style subculture, English football casuals and Madchester ravers. But its bubbling origin story in Bologna is even more exciting and avant-garde. ‘The imprint of the city is very strong. That was the environment where the brand was born. Everybody was left-wing in our family, friends, but also the wider community. Honestly. I didn't know anybody who was right-wing, probably up till I was 30.’

Images from C.P. Company 971-021: An informal history of Italian sportswear

Born in 1974, Lorenzo grew up alongside the brand, and he paints a romantic, quasi-revolutionary picture of the early days of C.P. Company before his father left it in 1995 (he passed away in 2005). I imagine the Osti household to be full of pattern cuttings, garment experiments and wild-dyed fabrics, but he says it was more about the rampant socialising and big discussions. ‘It was really an open house. Every night we had people ringing at the door saying, “Oh, there is something for dinner?” And there’d end up being 20 people every day. The conversation was very exciting. I remember the energy. I never wanted to go to sleep. I usually fell asleep with people talking about politics. It was a stimulating environment of work and life. Most of my father’s colleagues were his close friends. Nobody was from the fashion industry. There was not a scene here in Bologna. It was not Milan. Everything was in Milan. I think that gave the work a different edge and maybe made it more innovative and out of the box.’

Early adopters of the brand weren’t from the sportswear world – they were more likely to be political and aesthetic radicals. ‘I remember that there was a kind of specific client that was in love with C.P.,’ says Lorenzo. ‘They were sophisticated, very genuine people; the kind of people who really looked into details, listened to music with a lot of consciousness, had awareness of what they were doing. People who really lived life fully because they were hungry and interested in many things. I won't call them intellectuals – intellectual is a bit too narrow a description – but people who really experimented. They didn't want to just take what was there. It was made up of many different people from very different social situations.’

Massimo would hold court, giving away garments to his friends to see how they wore them and mixed them up. People couldn’t expect to keep the clothes for long though. ‘Maybe after one month he saw it again [and said], “You have to give it back.” He liked maybe the way someone mixed it up and so he took the idea and then changed the garment.’

Image from C.P. Company 971-021: An informal history of Italian sportswear

The 1960s and 1970s were a time when a new generation were breaking away from older codes, striving to define themselves anew. And it’s in this period that people sought out new ways to dress. ‘Their identity was built against the one of their parents. They were protesting against the Vietnam War and wearing the military parka as a uniform to be totally pacifist. There was this tension with the past. They wanted to change or flip something.’ Whereas the previous generation dressed formally and had a garment for every occasion (‘the suit to go to work, the coat to put over the suit, the hunting jacket if you're going to hunt, the tennis jacket if you’re playing tennis’), Massimo – who loved the worn-in look of the English aristocracy and always had holes in the elbows of his knitwear like any self-respecting British boarding-school boy – wanted lived-in, multifunctional garments.

‘The public were quite rigid and the function was pretty rigid,' explains Lorenzo. ‘There was no washing or treating the fabrics, so a new jacket looked out of the box. Then this new generation came in and they didn't identify with this apparel. My father didn’t like fabric or garments that looked new, so he started to wash and garment dye everything to give a used look. When you put that on a classic trench, it was totally different from any other brand, because it looked soft, used, comfortable. You were at ease in that. Some people have said, “What I liked about C.P. Company at that time is that they looked like they had always been mine.”’

C.P. Company's colour swatch archive

The ensuing years saw Massimo go on an obsessive colour trip, building an internal dyeing facility and becoming the first person to hire an in-house chemist (Giuliano Balboni) to push his clothing palette to its absolute limits. The brand became famous for its technical innovation and fabrics – all signatures that have been taken and advanced by ensuing designers Romeo Gigli, Moreno Ferrari, Alessandro Pungetti and Paul Harvey.

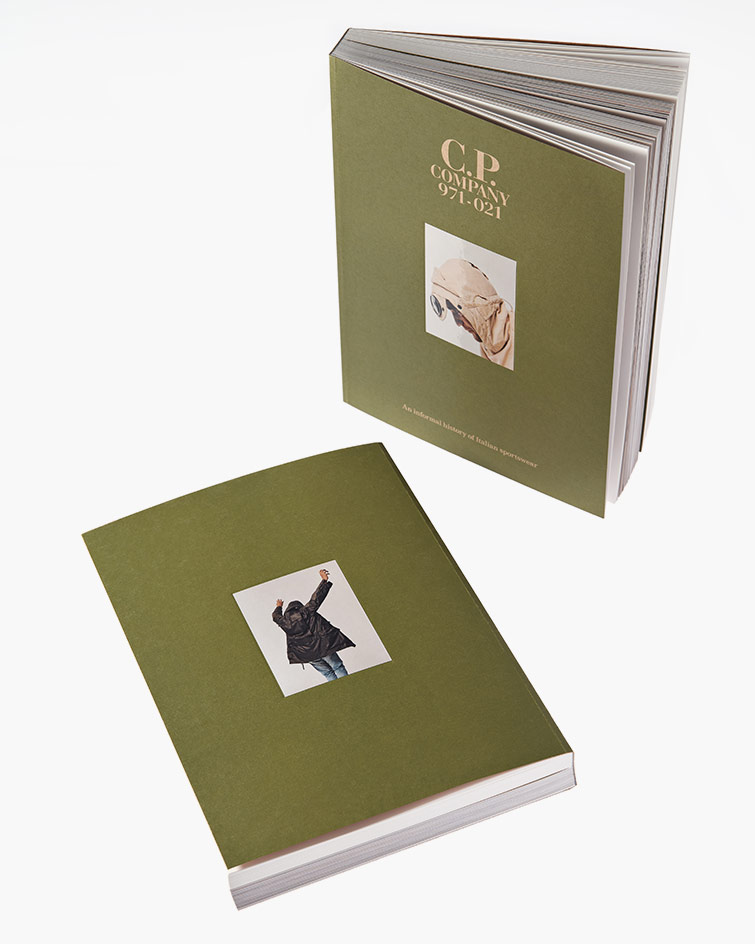

As it celebrates its 50th anniversary, the brand has photographed 50 people for its book C.P. Company 971-021: An informal history of Italian sportswear, including its own creative stars, as well as wide-ranging C.P. lovers from tattooists to teachers and rappers to postmen. For a label that’s been so heavily shaped by its devoted following, it’s only fitting that’s its customers appear alongside its creators in this monumental tribute.

CP Company 971-021: An informal history of Italian sportswear

A jacket highlighting the creative process behind constructing a CP Company design

Musician Shinsuke Yamaji wears CP Company. Image from CP Company 971-021: An informal history of Italian sportswear

INFORMATION

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.