Light installation by Random International

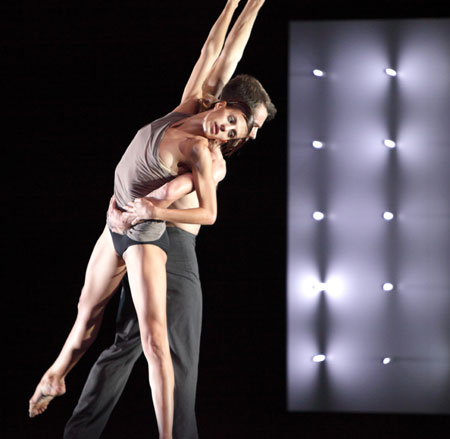

Random International's works have a life of their own. From the sound-reactive 'Swarm' chandelier to the movement-responsive 'Amplitude' installation, each of the studio's designs behaves in an idiosyncratic fashion. For Wayne McGregor's recent production of Far at Sadler's Wells, however, it unveiled its most audacious piece yet. Here, the dancers writhed, flexed and stretched on stage before a giant, pulsating screen of light with an ever-changing pattern.

'We're interested in pieces with their own autonomous character,' says Random International co-founder, Hannes Koch. 'The installation functioned like a second piece of choreography, though its pattern was not predetermined.' The start and finish of its algorithmic phrases were synched to the musical score and scenes, but within these parameters, it behaved as it liked. 'We didn't want to control the light too much - it needed to be its own entity on stage,' Koch explains.

Watch the installation in action

McGregor's production was inspired by medical historian Roy Porter's Flesh in the Age of Reason. The pioneering choreographer, whose past collaborators include artist Julian Opie and architect John Pawson, teamed up with neuroscientists to see how mind and body worked together for the performance, inviting Random International to the workshops to ensure continuity between dancers and scenography.

The resulting installation helped contextualise the choreography for the viewer and added to the multi-sensuality of the production. It acted like another, unpredictable personality on stage - just as you thought you recognised a pattern, it changed. Here, Hannes Koch reveals how this design feat came together.

Describe the brief that McGregor gave you?

Wayne didn't give us any visual guidance - that's the beauty of working with him. He never gives his collaborators strict guidelines. But joining him at workshops and his residency at EMPAC in New York in early 2010 helped us understand his working process and the direction in which he wanted to take the performance.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

As references, we initially showed him some of our kenetic and sound-reactive pieces but Wayne felt that interactive sets had been done too often. He wanted something that lived its own life. The piece needed to have its own form of artificial intelligence.

What were the challenges, aside from the obvious technological issues?

The installation needed to carry the set for 70 minutes without being too distracting. To prevent people from being dazzled, we made sure that the audience didn't look directly into the light source. Instead they looked predominantly at indirect light and shadows.

With the piece acting as a separate entity on stage, how did you ensure it didn't jar with the production?

We worked closely with lighting designer, Lucy Carter, who did a phenomenal job of incorporating it into the set by calming it when necessary or giving it more prominence, if required. And although the piece had its own distinct behaviour, the start and finish of the algorithms were coded to the performance.

What did you learn while researching this piece that you will take with you in future?

One of the cognitive scientists - Phil Barnard - pointed us to some research from the 1940s into how humans react to movement. Presenting people with some basic animations, the researchers discovered that humans can't see movement without attaching emotions to it. This fascinated us and has made us very interested in seeing how we can provoke a reaction in the viewer through our work.

What are you working on for 2011?

We'll be unveiling a lighting installation at Bloomberg's London office at the end of January. We are also creating a kinetic chandelier for early 2011.

’We’re interested in pieces with their own autonomous character,’ says Random International co-founder, Hannes Koch. ’The installation functioned like a second piece of choreography, though its pattern was not predetermined’

The start and finish of its algorithmic phrases were synched to the musical score and scenes, but within these parameters, it behaved as it liked

’We didn’t want to control the light too much - it needed to be its own entity on stage,’ Koch explains

McGregor’s production was inspired by medical historian Roy Porter’s Flesh in the Age of Reason

The pioneering choreographer, whose past collaborators include artist Julian Opie and architect John Pawson, teamed up with neuroscientists to see how mind and body worked together for the performance

Random International was invited to a series of workshops with McGregor, to ensure continuity between dancers and scenography

The resulting installation helped contextualise the choreography for the viewer and added to the multi-sensuality of the production

It acted like another, unpredictable personality on stage - just as you thought you recognised a pattern, it changed

To prevent people from being dazzled, Random International made sure the audience didn’t look directly into the light source. Instead they looked predominantly at indirect light and shadows

Malaika Byng is an editor, writer and consultant covering everything from architecture, design and ecology to art and craft. She was online editor for Wallpaper* magazine for three years and more recently editor of Crafts magazine, until she decided to go freelance in 2022. Based in London, she now writes for the Financial Times, Metropolis, Kinfolk and The Plant, among others.