Superflex on building an underwater city for fish: ‘there are different rules down there’

Danish art collective Superflex discuss their ambitious Super Reef, an underwater urbanisation project aiming to restore more than 55 square kilometres of stone reef in Danish seas

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

‘In many ways, the sea is the global unconscious,’ says Rasmus Nielsen, who founded Danish artist collective Superflex alongside Bjørnstjerne Christiansen and Jakob Fenger. ‘It’s almost like falling asleep, where you break through this surface. There are different rules down there.’

Superflex, known for its politically charged projects described as ‘tools for action’, has long been interested in the state of our seas. As Nielsen notes: ‘a healthy ocean is good for all of us’. Through the years, Superflex has experimented with different watery facets – creating a drive-through cinema in the Coachella Valley for Desert X using a coral-like material with projected footage of fish (Dive-In, 2019), a video of a deep-sea organism known as a siphonophore across the façade of the United Nations Headquarters in New York (Vertical Migration, 2021) and even interviews with marine life (What do you dream of?, 2018).

Dive–In, 2019, was originally commissioned by Desert X in collaboration TBA21–Academy with music composed by Dark Morph (Jónsi and Carl Michael von Hausswolff)

Superflex, Dive-In, 2019

Superflex and the Super Reef

In November 2022, Superflex announced an ambitious project to restore a minimum of 55 square kilometres of stone reef in Danish seas, in partnership with the World Wide Fund for Nature. This is the amount estimated by scientists to have been removed by humans to build their own homes and structures: ‘We took all the stones away where [fish] had their nests and crevices and cities – fish cities so to speak – and turned them into our cities.’ Of course, Superflex won’t restore this vast area known as the Superrev (or Super Reef) singlehandedly. They hope the project will galvanise local communities and organisations: ‘You could think of it as an underwater urbanisation process that could inspire a whole nation.’

Super Reef began in 2018 with a journey across the Pacific. Francesca Thyssen-Bornemisza, whose foundation Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary (TBA21) is devoted to social and environmental advocacy, invited Superflex to lead three expeditions on the Dardanella research vessel. TBA21 imagined Superflex might be joined by other artists, but, Nielsen recalls wryly, the collective asked a crew of scientists along for the ride instead. They were struck by the effects of climate change they encountered, like the communities of Tuvalu and Kiribati that lie just a few metres above sea level, which ‘might be moving away in a generation or so because they can’t live there, it’s going under’.

Flooded McDonald's, 2009. RED, 21 min. Still image

In many ways, Superflex’s engagement with the ocean echoes our own coming to terms with the climate crisis. Nielsen remembers the attitude in the 1990s that the right technology could solve all Earth’s problems. By the 2000s, there was a more ‘melancholic acknowledgement’ of climate change, as in the film Flooded McDonald’s (2009), where a life-size replica of the fast-food restaurant silently fills with water. Nielsen describes the work as a vision of the end of the world, in a ‘mild Scandinavian way’. More recently, science and art have become more closely entwined. ‘We’re being flooded,’ Nielsen says. ‘But you know, there are ways of mitigating, of working in that conceptual framework.’

‘Imagine a fish Ikea in the water’

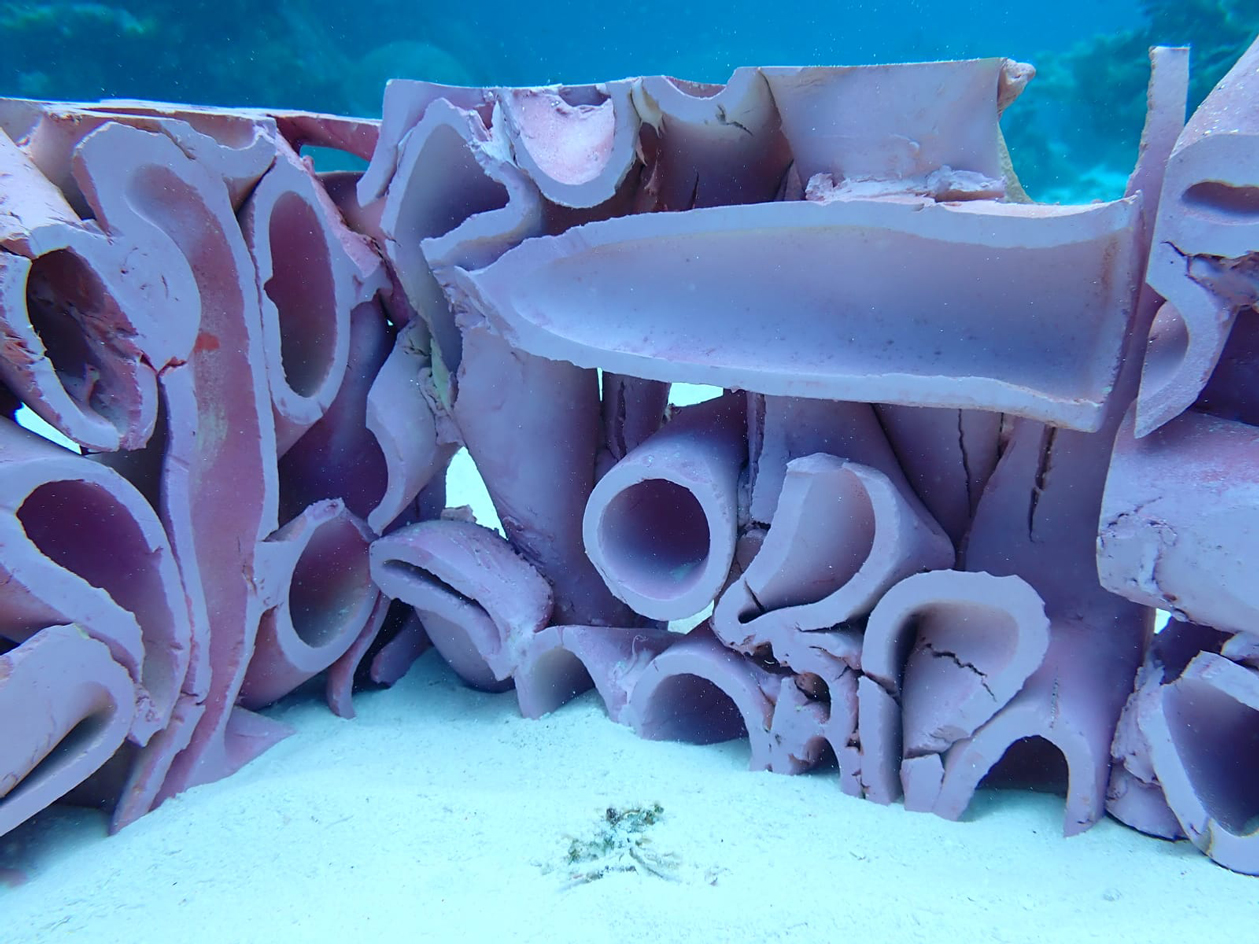

Superflex’s research project Deep Sea Minding, which came out of the TBA21 commission, has sparked all manner of experiments with materials, from aluminium foam to ceramic to concrete, that have been dropped into the ocean to see the response of fish. ‘Imagine a fish Ikea in the water,’ Nielsen explains.

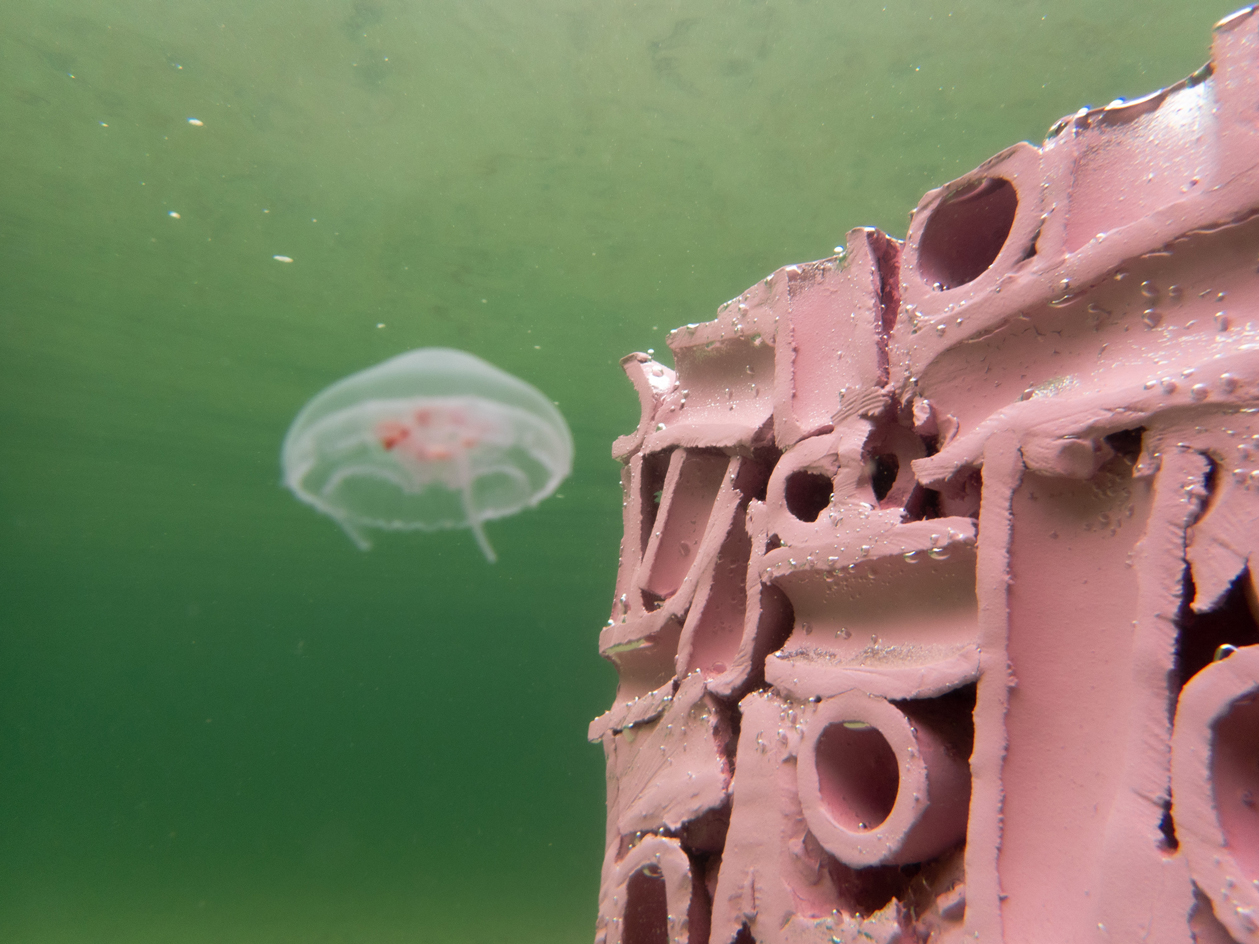

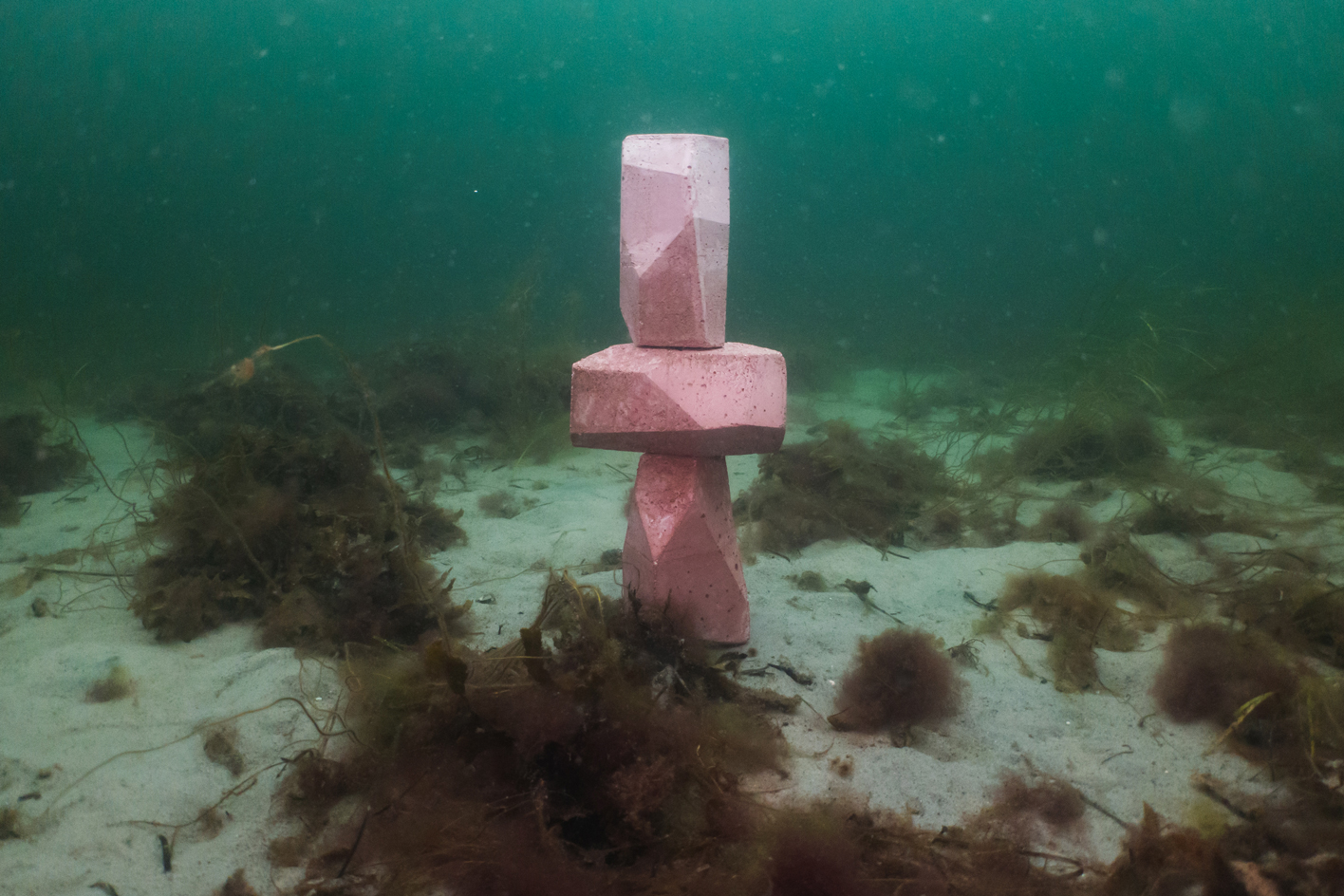

Projects like As Close As We Get (2021) and Pink Elements (2019) also emerged, with their bubble-gum pink colouring and abundant surface area that look like sculptures but will become underwater fish homes when the seas rise and delight coral polyps (‘the architects of the sea’). In March 2023, Superflex and VogelART announced a new series of glazed ceramic building blocks called the Interface Brick, a collectable object that can also be used for underwater construction.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

From Superflex's second expedition commissioned by TBA21–Academy, Deep Sea Minding: Surface, which focused on testing the placement of interspecies architecture featuring a larger structure and better circulation in Papua New Guinea

From the Deep Sea Minding: Surface expedition in Papua New Guinea

Superflex’s voyage around the Pacific curiously echoes the journey of another rag-tag group of innovators – the International Congresses for Modern Architecture aboard the Patris II in 1933. Sailing from Marseilles to Athens, modernist architects like Le Corbusier sipped cocktails and devised the Athens Charter that would form the blueprint for modern cities of the future. Superflex has devised its own set of architectural principles in collaboration with WWF, with the future cities of fish, molluscs and algae in mind. ‘We thought we could make a sort of underwater version – the wet version,’ Nielsen says.

Characteristic of their intrinsically collaborative practice, Superflex realised any underwater project would need to involve its inhabitants, ie – the fish. In contrast to the human-centric nature of city planning, marine cities would need to place fish at the heart of any scientific or aesthetic decisions. In the past, Nielsen has even referred to fish as ‘the clients’.

Superflex, As Close As We Get, 2022 (detail) Mixed materials

In 2021 Superflex was the recipient of the Crown Prince Couple Cultural Award organised by the Bikuben Foundation. As part of the award acceptance video, the artists invited HRH Crown Prince Frederik on a dive to set an As Close As We Get sculpture, in a symbolic gesture to kickstart the project Super Reef, which has since involved a partnership with WWF

Nielsen highlights how easy it is to separate ourselves from the fate of the ocean, despite the fact that two-thirds of the human body comprises water. ‘If you cry,’ Nielsen notes, ‘the tears have the same amount of salt as is in the ocean. So, we have oceans within us in a strange way.’ The only reason why we don’t have a stronger reaction, perhaps, to the sight of the catch of the day is because fish can’t scream. But that is what they are really doing.’

With the outbreak of Covid-19, Superflex’s adventures across the Pacific came to an end, but back in Copenhagen, ‘we realised, actually, there is an ocean right out there as well’. Superflex decided to apply the knowledge they had acquired to a local Danish context, where the loss of the stone reef has stripped the local fish community of places to attach, hide, and be idle. The Danish sea has its own history, as Nielsen explains: ‘We are fundamentally a nation of stone fishers and Denmark is sand and mud. It's shaky ground!’ he laughs. ‘The main body of us is a sea – not a very healthy sea, because of what we’ve pulled out of the sea, because of trawling, and so forth.’

In 2022, Superflex placed a series of modular structures of fish-friendly bricks in Copenhagen harbour for the project As Close As We Get – part artwork, part scientific experiment, part maritime home; the Crown Prince of Denmark laid the first cornerstone of the Super Reef, which, as the project unfolds, will pave the way for the era of the fish.

Superflex, As Close As We Get, 2022, realised in collaboration with DTU Sustain and By & Havn. The project was supported by the Danish Art Council. This experiment is conducted in collaboration with DTU Sustain and By & Havn. Supported by @statenskunstfond

Superflex, As Close As We Get, 2022

Superflex, There Are Other Fish In The Sea, 2019. Installation view. Galería OMR, Mexico City, 2019

Superflex, Super Reef