Lagos Biennial 2024: the highlights

Lagos Biennial 2024 took over the city’s Tafawa Balewa Square with the theme of ‘refuge’

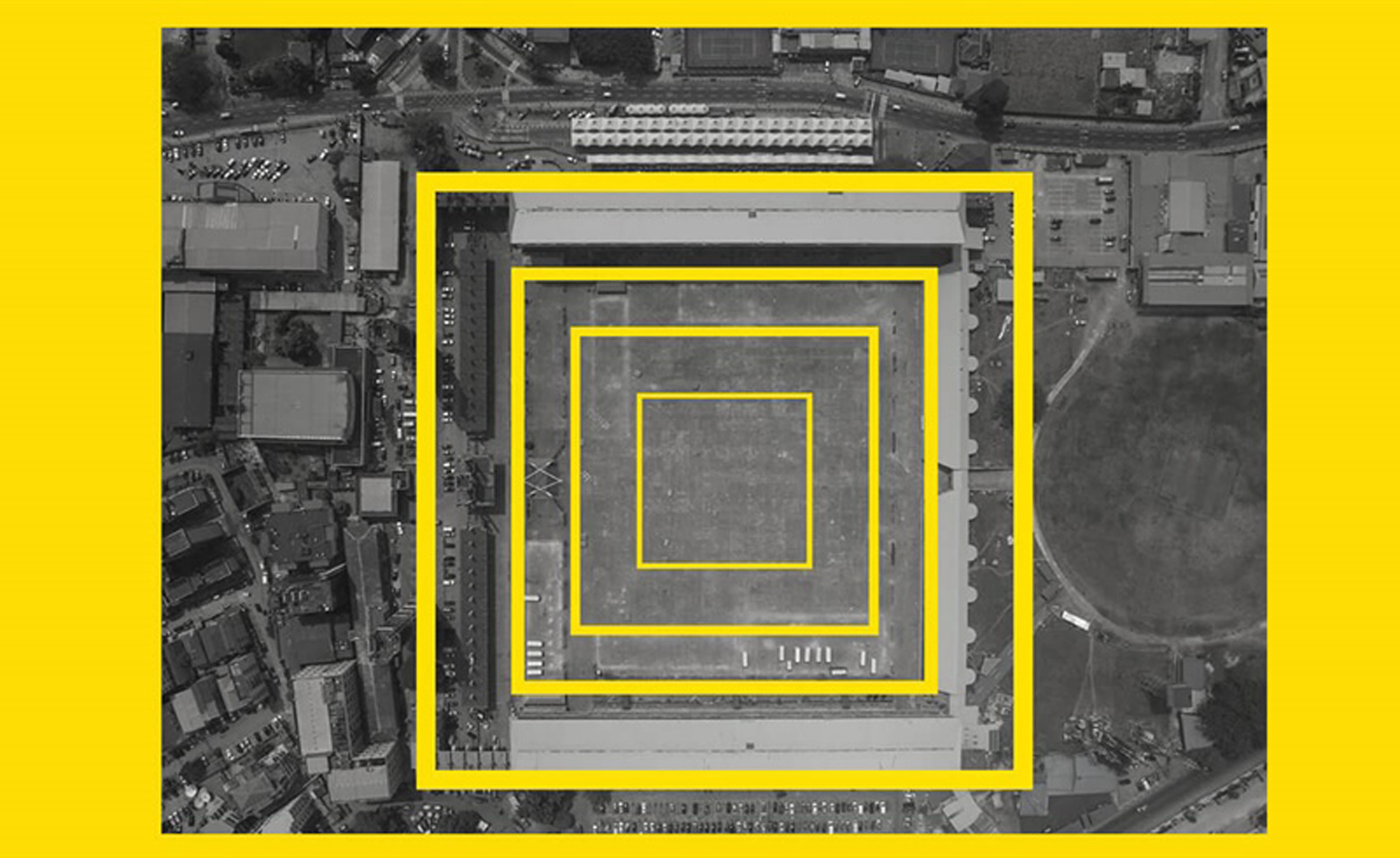

Lagos Biennial 2024 (3 – 10 February), the event’s fourth edition and a return after a two-year hiatus, was held with the theme ‘refuge’, at the Tafawa Balewa Square, an address honouring Nigeria’s first prime minister upon independence, Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa. The biennial was founded in 2017 by an artist collective under the Àkéte Art Foundation; it has since been dedicated to the curation, presentation and critical discourse of art in Africa, adding to the conversation around politics, economic and social complexities across the continent.

The 2024 edition featured a host of creatives across architecture, arts, fashion and film spaces, all interpreting the refuge theme in their own way and shaping their works through it.

Lagos Biennial 2024 highlights

Miracle Central by Victor Ehikhamenor

Miracle Central

In what would be regarded as the tallest installation at the biennial, visual artist Victor Ehikhamenor fused art with architecture, creating a grand installation titled Miracle Central that took the viewers back to the 2000s. The installation, a dialogue on religion, and the long chokehold it has held on Nigeria for decades, took viewers into a ‘church’ clad with thousands of white handkerchiefs, which symbolise the Pentecostal movement in the country. Everything within the installation is suspended in the air, from floating chairs and musical instruments to the pulpit and the microphone stand. By laying several mirrors on the floor, Ehikhamenor rendered equality before God. ‘With Miracle Central, I extend the focus of my ongoing interrogations on the duality found in expressions of religion and culture to Pentecostalism,’ Ehikhamenor said. ‘Miracle Central invites meditation on the hallowed space to be found at the intersections of religion, politics, history, and expressions of belonging.’

Human hive 3 by Chinenye Emelogu

One of the most memorable installations for its bold and vibrant colours, Human Hive 3 invited viewers to approach it with their own interpretations. The work is artist Chinenye Emelogu’s way of creating a social structure that doesn’t feel strange or influenced by societal expectation. Emelogu was inspired by the social patterns of bees, their communal struggle to create a utopia, and she tries to create a dialogue with happenings in Nigeria, posing questions about what utopia means for the country and how Nigerians can work towards it. The installation was made from strips of plastic rings used in product packaging.

‘Traces of Ecstasy’ a pavilion curated by KJ Abudu

Nolan Oswald Dennis

Titled after an essay by the British-Nigerian visual artist Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Traces of Ecstasy is an architectural pavilion that features alongside an art exhibition and symposium, and premiered at the Lagos Biennial 2024. It was curated by KJ Abudu and features the work of creatives from various fields: Evan Ifekoya, Nolan Oswald Dennis, Raymond Pinto, Adeju Thomspon and Temitayo Shonibare. In the pavilion, viewers were met by a visual installation that explained key moments in Nigeria’s history, from the 1960s to the modern day, including independence and #EndSars (a movement against police brutality in Nigeria), as well as a video on 1980s Area Scatter, Nigeria’s first crossdresser. Sound and fashion installations are presented in the form of calabash sound systems and floating adire (tie-dye) fabric. ‘Traces of Ecstasy aims to unsettle the colonial capitalist power structures that maintain and reproduce the ideological legitimacy of the nation-state in post/neocolonial Africa,’ said Abudu.

Yakachana by Ibrahim Mahama

Yakachana by Ibrahim Mahama addresses ecological concerns, and what it is like to share space with other organisms, in an artistically grotesque installation featuring decayed bags. Mahama looks back to Ghana in the 1960s, the abandonment of buildings, and how they became home to other creatures and organisms. The installation, made of jute sacks used to transport cocoa, sees the artist investigate failed global systems and the problem of industrialisation. ‘Through my work and the kind of objects that I use – old decayed or discarded materials to create large-scale installations and site-specific interventions – I realised that the abandoned buildings had really interesting qualities,’ said Mahama.

Betok babhi, Babhi betandat, bassem, by Em’kal Eyongakpa

Em’kal Eyongakpa created vivid sonic experiences for viewers in the form of a beautiful installation built with nets and almost a thousand crates of eggs. Vibrations and motion were key, with viewers standing on top of a vibrating wooden platform to experience different frequencies and modes. Eyongakpa examined collective histories of habitats, how they mimic, evoke and employ elements and natural phenomena. The piece takes inspiration from poly-rhythmic beat generators and sonic activations from refugee camps in Cross River, South South Nigeria, where the artist had created an art community.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Omo elu by Tabita Rezaire

Textile art meets spirituality in Tabita Rezaire’s installation, featuring seven clay-stained indigo fabrics that paid homage to Yemoja, the mother of the Orishas and the goddess of water. Each textile piece embodies a spiritual awareness. Differently sized calabashes with cowries placed at the centre of the installation symbolised a ritualistic form of practice. ‘Omo elu is an ode to the nuances of blue, echoing the many paths of Yemoja: Yemoja the mother, the warrior, the creator, the healer, the ruler, the dancer,’ said Rezaire.

Ugonna-Ora Owoh is a journalist and editor based in Lagos, Nigeria. He writes on arts, fashion, design, politics and contributes to Vogue, New York Times, Wallpaper, Wepresent, Interior Design, Foreign Policy and others.