‘Nigerian Modernism’ at Tate Modern: how a nation rewrote the rules of art

At Tate Modern, ‘Nigerian Modernism’ redefines what we mean by modern art. Tracing a half-century of creative resistance, the landmark exhibition celebrates Nigeria’s artists as pioneers of form, freedom and cultural imagination.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Stepping into Tate Modern, the proposition is immediate: modernism is plural and Nigeria is one of its centres. ‘Nigerian Modernism’ opens as a conversation, not a line. Media and generations collide. Ceramics answer painting. Print meets sculpture. Osei Bonsu and Bilal Akkouche curate with a choreography that mirrors the experimental drive of the work itself. Opening tomorrow, the exhibition brings together more than 250 works by over 50 artists, spanning the 1940s through to the late 20th century. What emerges is not a tidy lineage but a restless dialogue – a testing ground for freedom, imagination, and struggle.

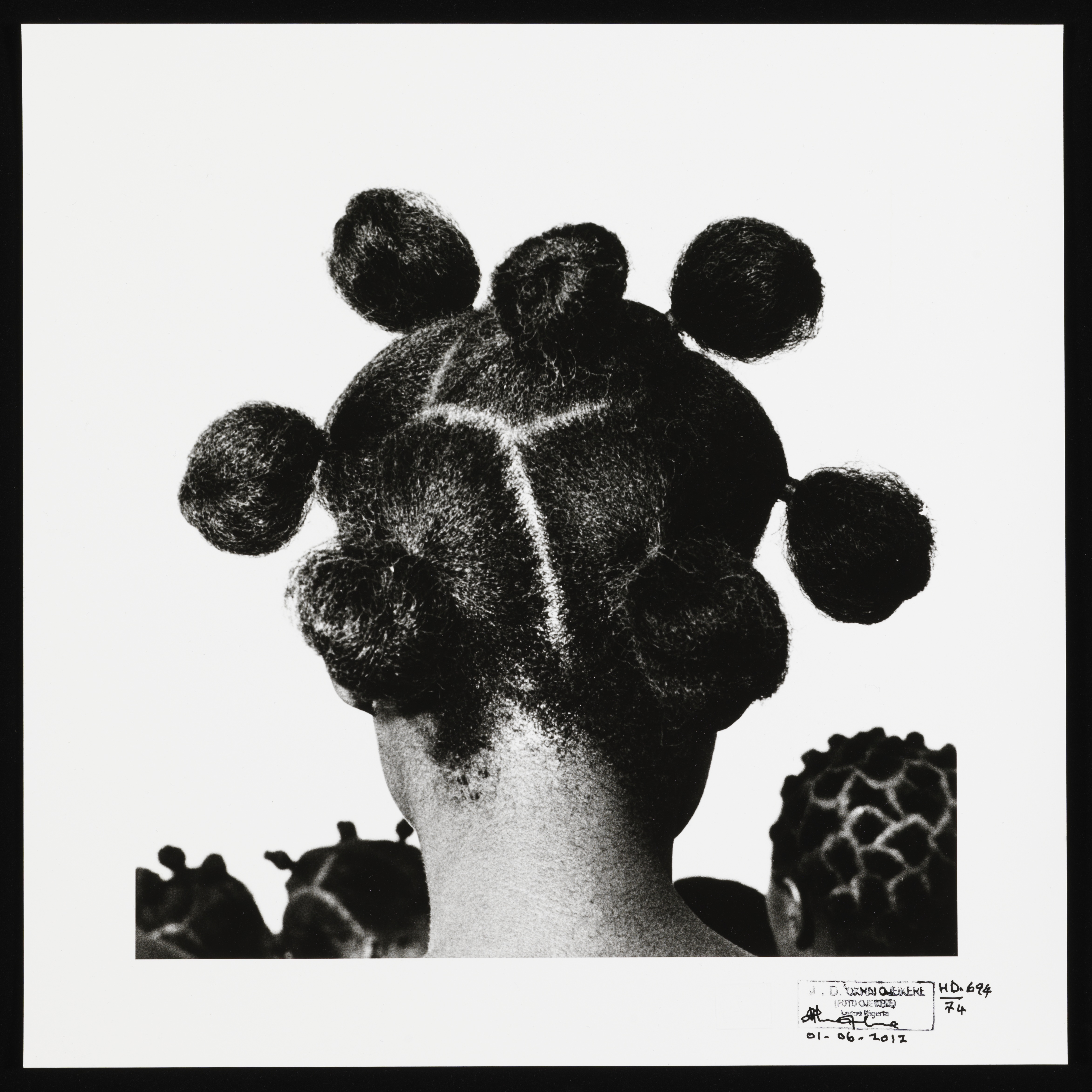

JD Okhai Ojeikere, Untitled (Mkpuk Eba), 1974, printed 2012

By the time Nigeria gained independence in 1960, a generation of artists had already begun to craft a new visual vocabulary that challenged colonial hierarchies and asserted cultural pride. The exhibition maps this shift as both a personal and collective journey. It opens in the 1940s, in the early stirrings of decolonisation, when British governance still shaped Nigeria’s education system, and many artists left to study in Britain. They absorbed European methods, yet their ambitions lay elsewhere: to centre Indigenous forms, to wrest back sovereignty, to place Nigerian art within the broader story of modernism on its own terms.

Ben Enwonwu, The Dancer (Agbogho Mmuo - Maiden Spirit Mask), 1962

The gallery vibrates with atmosphere. Paintings, sculptures and prints are accompanied by the soundscapes of Lagos, threaded through by a playlist curated by Peter Adjaye. The rhythms call up the city’s nightclubs at their height and, more deeply, the transatlantic journeys that carried diasporic traditions back to West Africa. Out of those returns came highlife, a genre born of fusion: part memory, part invention, a cultural lingua franca that transcended borders. To hear its pulse inside the museum is to understand that Nigerian modernism is not only a visual project but a sonic and social one, alive with political consciousness.

Justus D Akeredolu, Thorn Carving c.1930s

Walking through the exhibition, one is struck by a sense of beauty that has been missing from London’s cultural landscape. Until now, the city’s relationship to African modernism has been mediated by the art market, with Bonhams among the few institutions to establish a global profile for modern and contemporary African art. Here, however, the works are liberated from the auction room. They appear as stories and legacies, as textures of belonging. The galleries feel almost domestic, familiar in palette and rhythm, resonant in sound. It is as though an untold history, long at the margins, has been waiting for this moment to announce itself.

The exhibition’s final act centres on Uzo Egonu, an artist who spent much of his life in Britain and whose Stateless People series from the 1980s is reunited here for the first time in four decades. His solitary figures – a musician, an artist, a writer – are both portraits and archetypes, reflections on displacement and the unstable search for belonging. Egonu demonstrates that Nigerian modernism did not end with independence or the trauma of civil war. It continues in the diaspora, in the friction between memory and exile, in the act of carrying fragments of home into other worlds. Though later embraced by the British Black Arts Movement, Egonu refused neat categorisation, insisting on a radically independent practice that secured his position as one of the most important Nigerian artists in the global diaspora.

Throughout, Bonsu and Akkouche resist the comfort of chronology. Instead, they stage connections: Lagos to Zaria, Ibadan to Nsukka, London to Munich and Paris. The exhibition moves like a web, tracing networks between practice, medium and geography. History is kept alive, not pinned down. The curators argue persuasively that Nigerian artists are not adjuncts to modernism but its engine, its rhythm, its core.

What emerges is not a monolith but a chorus. Experiments collide. Traditions are bent and reshaped. Local knowledge is folded into international form. The questions raised are pressing, not past tense. How does a nation narrate itself after an empire? How can inheritance circulate globally without being consumed? What would it mean for museums to write histories that hold multiplicity and mastery together, without compromise?

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

El Anatsui, Solemn Crowds at Dawn, 1989

The rooms themselves thrum with tactility. Ceramic vessels incised with geometric skin. Prints thick with relief. Canvases alive with heat and procession. Objects sit in deliberate proximity, sparking visual conversations: a Kwali pot beside an Enwonwu canvas, an Onobrakpeya relief catching light near an Egonu geometry, reading tables scattered with Black Orpheus and other journals that once shaped cultural debate. The rhythm of the exhibition encourages slow looking, drift and return. Eight rooms hold half a century of work, carrying us from the euphoric pulse of independence to the quieter registers of reckoning, resistance and renewal.

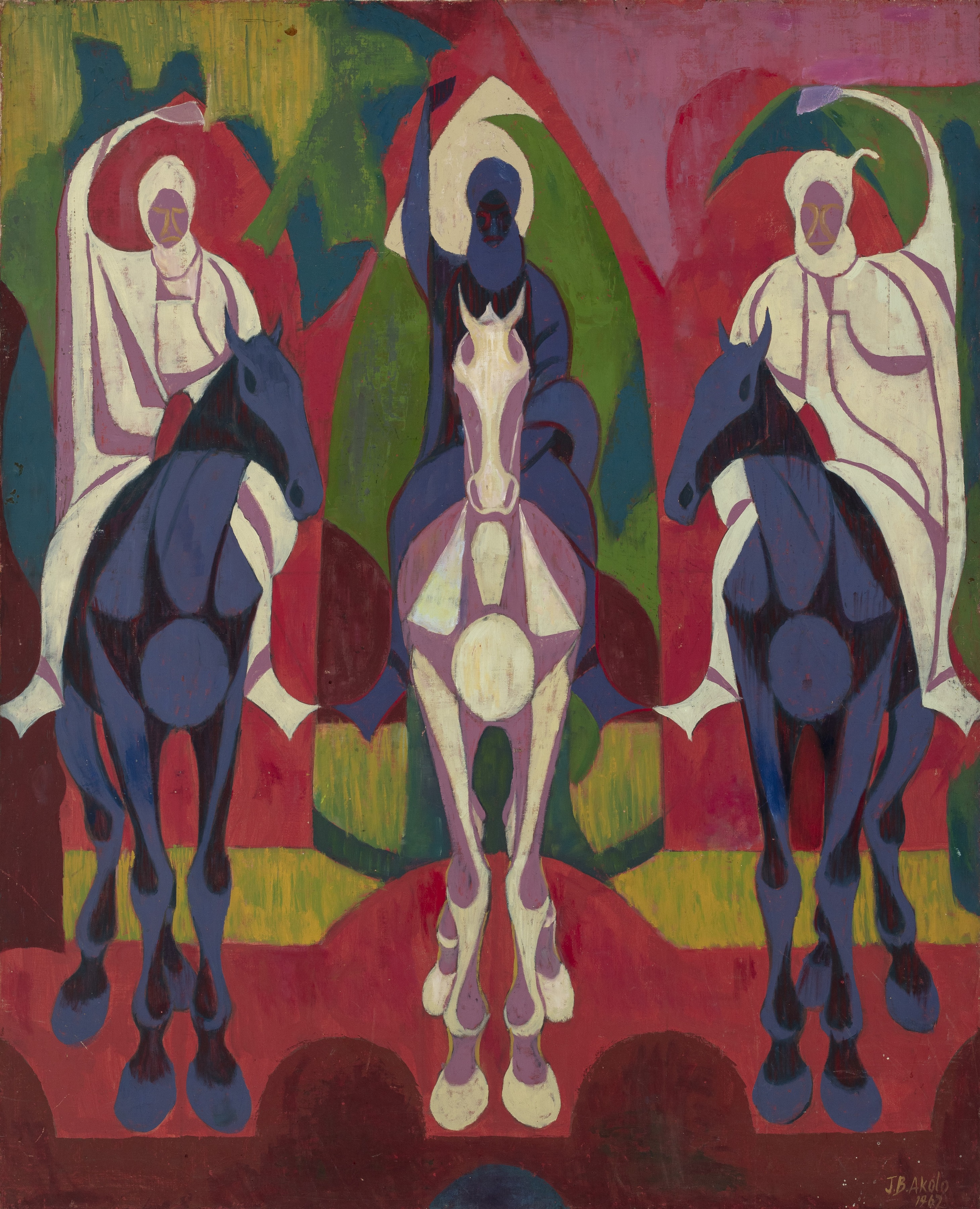

Jimo Akolo Fulani Horsemen, 1962

To walk through ‘Nigerian Modernism’ is to encounter art as inheritance: ancestral forms carried forward, reshaped, made new. It is also to see artists holding a mirror to the nation, reflecting not only vitality but also fracture. History here is not offered as a fixed account but as a sequence of encounters – between continents, between generations, between tradition and innovation.

At its core, ‘Nigerian Modernism’ does more than fill a gap in the canon; it rewrites the canon altogether. Each room reveals how artists turned knowledge into action, technique into language, art into infrastructure. They built schools, founded clubs, created forms the world had never seen. Their project was not about style, but about freedom.

The lesson is inescapable. These are not decorative footnotes to history. They are history. They bear the burden of responsibility, the devotion to skill, the urgency of a nation imagining itself anew. To leave the exhibition is to leave instructed, altered, unable to look away.

‘Nigerian Modernism’ is at Tate Modern, London from 8 October 2025 to 10 May 2026, tate.org.uk

Jamilah Rose-Roberts is Wallpaper’s Social Media Editor. Alongside shaping the brand’s social media presence, she writes about the arts with a focus on cultural narratives, the diaspora and contemporary practice. She enjoys meeting artists and designers, visiting exhibitions, and conducting interviews. Her work draws on a background in arts writing and luxury fashion, bringing a curatorial sensibility while expanding conversations around design, culture, and creativity.