Claude Cahun’s surreal challenging of gender placed her a century ahead of her time

‘Claude Cahun: Beneath this Mask’, the Hayward Gallery Touring exhibition, is at Lakeside Arts in Nottingham until 17 March 2024

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

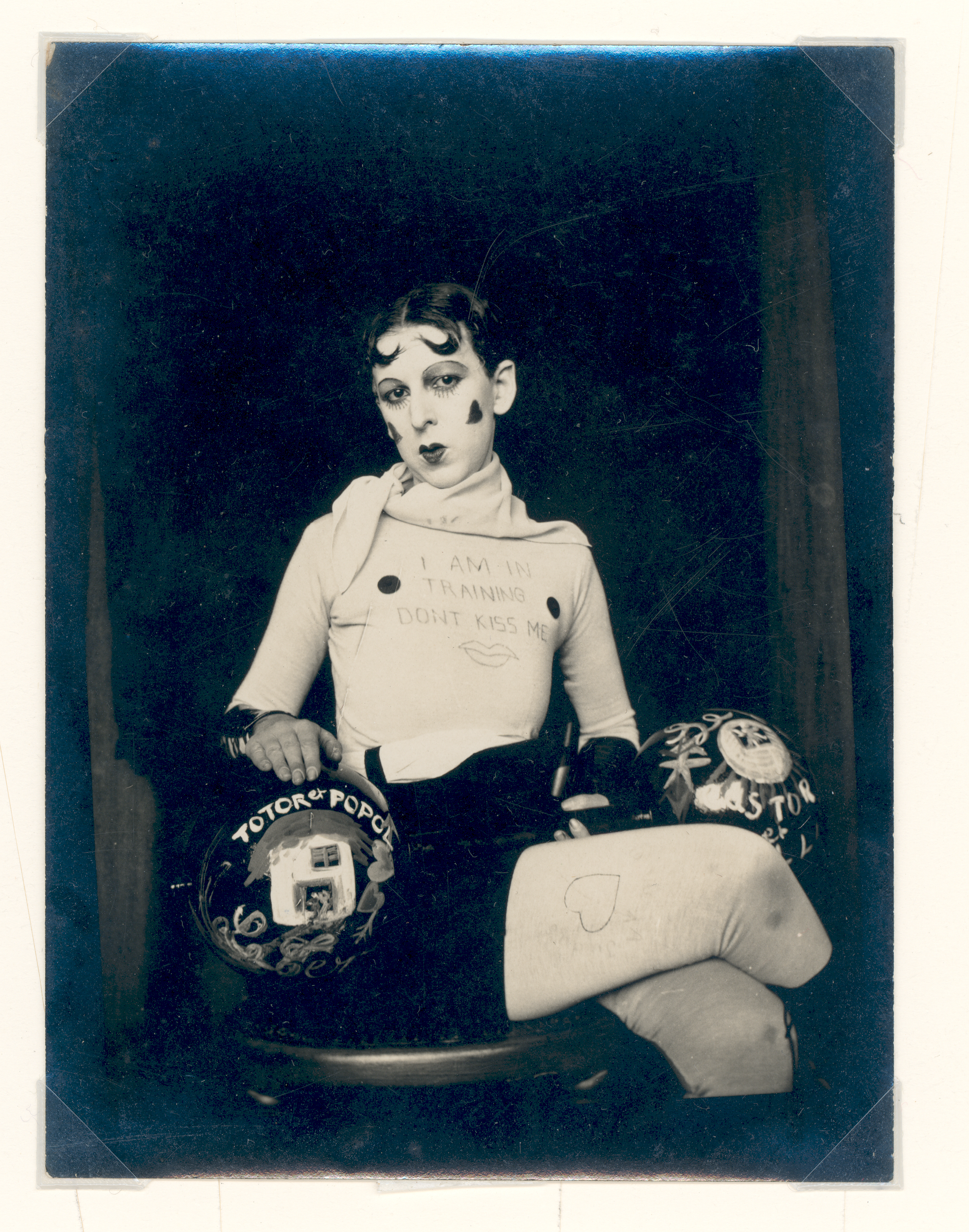

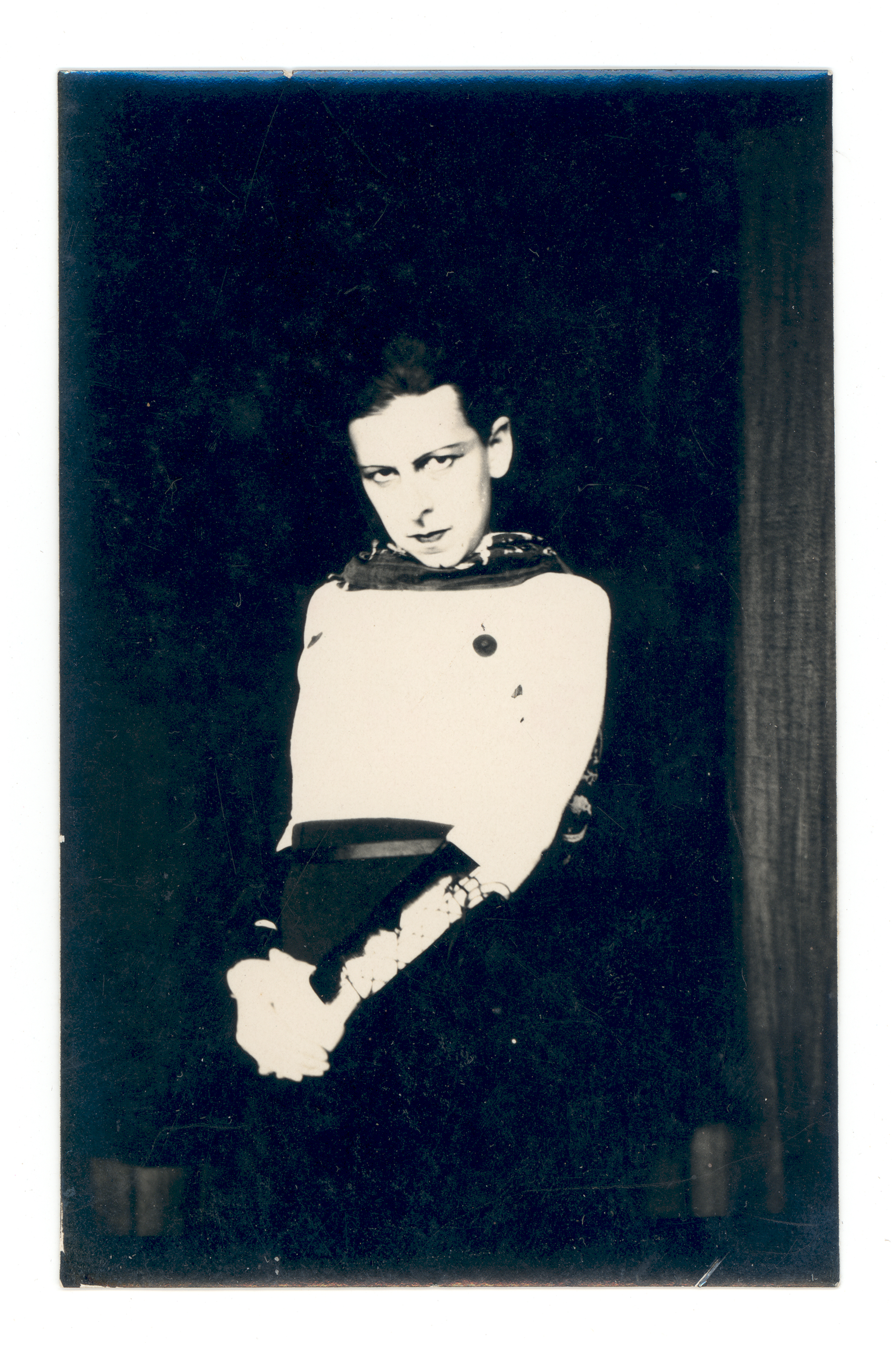

Claude Cahun was working about a century ahead of her time. In recent years her photographs have gained a significant audience, thanks to her experimental cosplay, which challenged gender binaries. With her partner Marcel Moore (both artists’ names were pseudonyms), Cahun worked first in Paris in the 1920s, and then in Dover at the outbreak of the Second World War. The Hayward Gallery Touring exhibition ‘Claude Cahun: Beneath this Mask’ is currently showing at Lakeside Arts in Nottingham (until 17 March 2024).

Claude Cahun: Beneath this Mask

Claude Cahun, I am in training, don’t kiss me, 1927

The first iteration of the exhibition opened as part of the Women of the World Festival in 2017, and the show’s curator Gillian Fox has noticed how much the context of Cahun and Moore’s boundary-pushing work has changed even in that time. ‘It’s becoming astoundingly more current as it goes on,’ she says, referencing mainstream attitudes towards gender expression, which have become more conservative in the last decade, and the growing interest in cosplay. ‘She was so astoundingly ahead of the curve and I think her work has gained in its currency.’

While Cahun’s face is in front of the lens, Moore is credited with much of the photography. ‘I think what will come out more is that they were a double act,’ says Fox. ‘That’s been totally underrecognised. They were always collaborators: two people acting as one with Cahun as the frontispiece.’

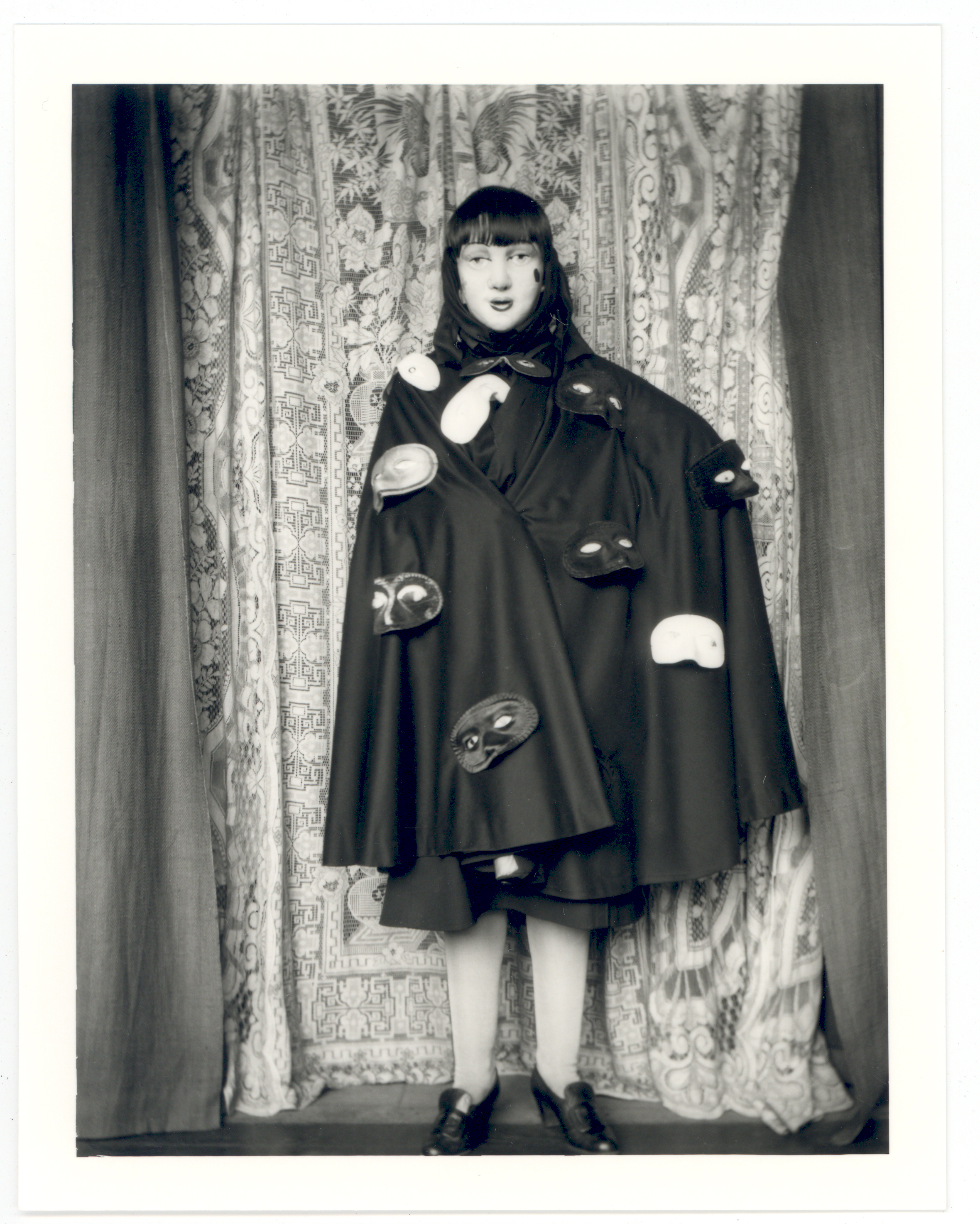

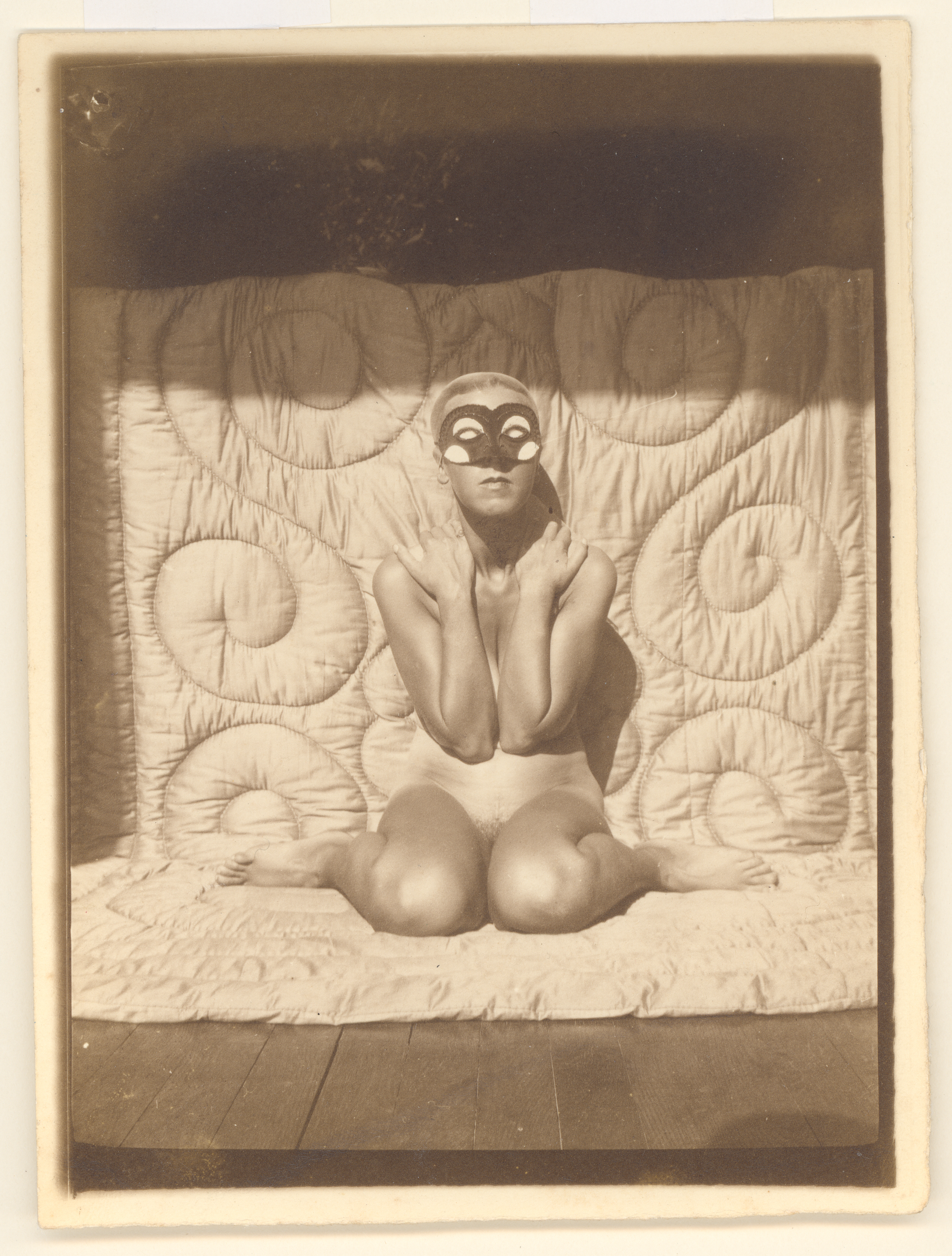

When Cahun was living in Paris, as a close friend of André Breton, she was seen as part of the surrealist movement. The duo’s work explores psychological expression and dark fairytale, which connects strongly with the surrealists’ ideas. But their treatment of women, who were often seen as objects within the work rather than drivers of it, alienated Cahun, with her progressive attitudes towards gender.

Claude Cahun, Untitled, c.1928

‘She was on the periphery of the Parisian intelligentsia,’ says Fox. ‘She was very radical and I don’t think anybody knew what to do with her. The surrealists were a machismo bunch and had some very traditional values. I think they may have seen her as more of an oddity, someone whom they could theorise about. Everything she did was for herself; she was the definition of a real artist. The practice itself was the motivation. It was an integral part of who she was, as an intellectual, in her own body.’

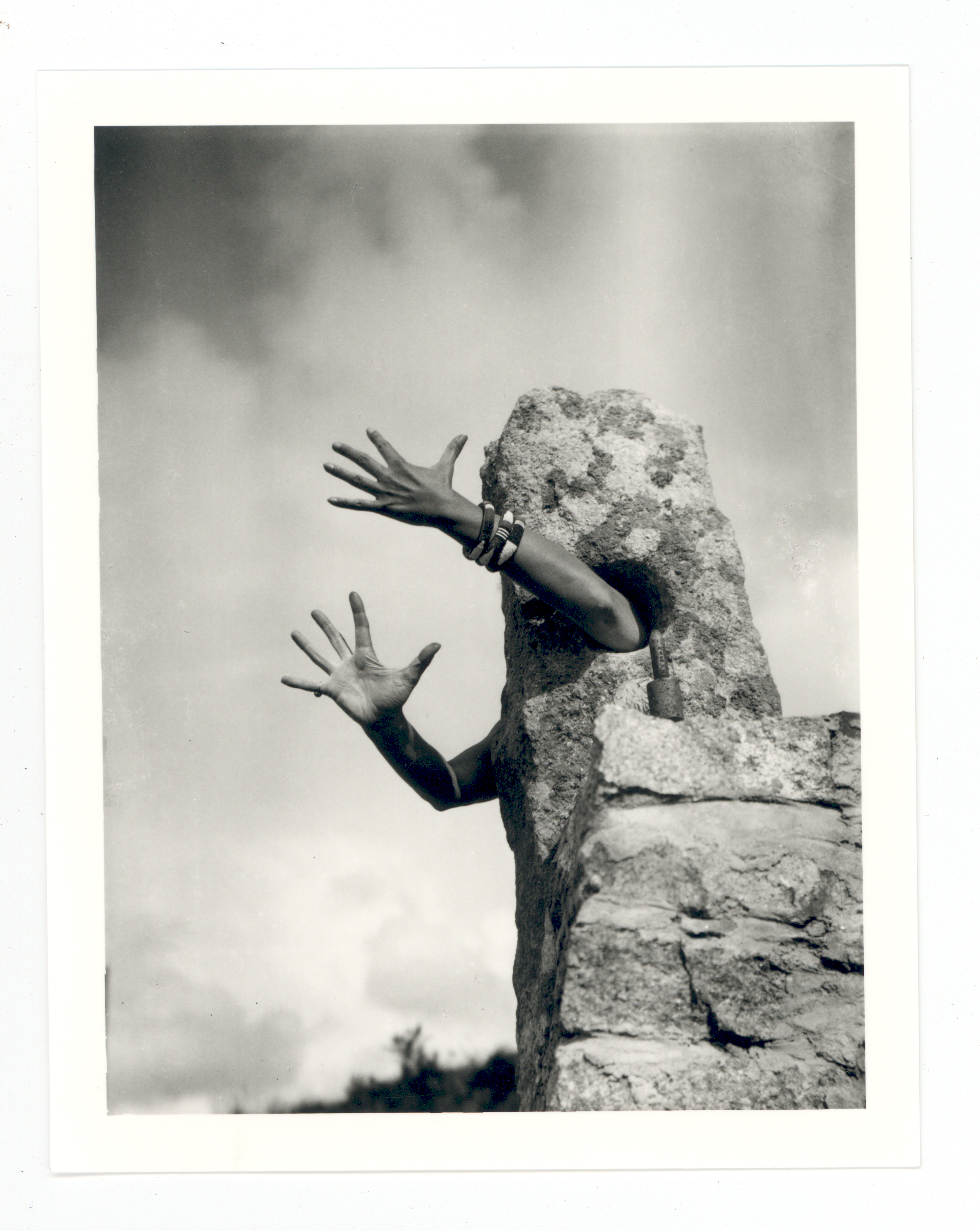

Cahun and Moore’s images touch on dream states, and the pair often worked with reflective surfaces to evoke a sense of the examined self. The works feel playful, with the two artists creating their own fantastical world. ‘It was so embedded in fairytale, and some of it was really macabre,’ says Fox. ‘There are these heads in bell jars, and you think, oh my God, paging Dr Freud! There were the floating heads; the disembodiment. Cahun made herself like a mannequin and she played that role, which I think showed how she saw herself in the world, this otherness.’

Claude Cahun, Self Portrait, 1928

Much of the work was destroyed during the Nazi occupation of France, when the pair were arrested for creating fake German communications and publishing propaganda posters. They were sentenced to death, though eventually released. Cahun died of health issues sustained in prison in 1954 and Moore by suicide two decades later.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

The work is a testament to their resistant spirit, which rallied against the subjugating structures of their time. They did this with frivolity and whimsy. ‘I would consider it a highly mischievous practice,’ considers Fox. ‘Cahun never stopped having the fascination of a child. The world that she and Marcel created allowed this sense of play and magical thinking which is now quite coveted.’

The Hayward Gallery Touring exhibition ‘Claude Cahun: Beneath this Mask’ is showing at Lakeside Arts in Nottingham until 17 March 2024

Claude Cahun, Self Portrait, 1932

Claude Cahun, Je Tends Les Bras, 1931

Claude Cahun, Untitled, c.1927

Emily Steer is a London-based culture journalist and former editor of Elephant. She has written for titles including AnOther, BBC Culture, the Financial Times, and Frieze.