Remembering Christian Boltanski (1944-2021)

French artist Christian Boltanski has passed away aged 77. Here, we revist our 2018 interview with the sculptor, who created the limited edition cover for Wallpaper's April issue that year (W*229).

‘Where are the cameras?’ I ask Christian Boltanski as we enter his studio in Malakoff, just outside Paris. He points out several, all feeding live footage to a grotto in Tasmania’s Museum of Old and New Art. In 2009, David Walsh, the professional gambler, art collector and founder of the museum (see W*141), agreed to pay Boltanski a monthly stipend until the end of the artist’s life for the right to film his studio 24 hours a day for an ongoing live video piece entitled The Life of C.B.

Walsh wagered that Boltanski would die within eight years; after that time, Walsh would end up spending more for the work than it was really worth. But those eight years have now passed, and the French sculptor and photographer still shows up on the feed – sitting at his computer, chewing on an unlit pipe, mulling over his next work. ‘He would like to see me die in real time,’ Boltanski says with a chuckle.

Mortality has long been a obsession for Boltanski. And yet, at 73, he’s still going strong, travelling the world, creating new works and mounting exhibitions. This spring, the Marian Goodman Gallery hosts his first solo presentation in London since 2010, with recent works including the film installations Animitas and Misterios. In his studio, there are sketches and models for upcoming museum shows in Shanghai, Jerusalem, Tokyo, and the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

‘He is certainly one of the major figures of the last 50 years,’ says Bernard Blistène, director of the Centre Pompidou’s Musée National d’Art Moderne and one of the first curators to give Boltanski his own show, back in 1984. He says the artist introduced an emotional dimension to conceptual art at a time when most others denied it. Since then, Blistène feels that Boltanski’s work has only grown deeper.

In Boltanski’s studio, large prints on veil from his Après series, alongside three small lenticular prints from his Signal series

Perhaps literally, too – Boltanski wants to put a section of his upcoming Paris exhibition in the museum’s underground car park. ‘I imagine that being up high, in the ‘glorious’ floors of the Centre Pompidou, and at the same time underground, is like saying that in every human being there is grandeur and misery, glory and confinement, high and low,’ remarks Blistène.

Boltanski has built his reputation on art that deals with disappearance and the fragility of memory, whether individual or collective. ‘A big part of my work is the fact that each person is unique and important, and that every person will disappear,’ he says, noting that most are forgotten after two generations.

His installations make use of everything from old photographs to heartbeats, which he has been recording from people around the world and is storing on the Japanese island of Teshima. With 120,000 heartbeats collected so far, The Heart Archive has become a pilgrimage site – though, he says, ‘If you go to hear your grandmother who is dead, you will listen to her absence more than her presence.’ Facebook intrigues him as a purportedly happy place where a growing number of profiles are of the deceased.

Boltanski’s limited-edition cover for the April 2018 issue of Wallpaper*, inspired by Arrivée et départ (Arrival and Departure), the last film of Alain Resnais. For Boltanski, the words ’Arivée’ and ’Départ’ were like the hyphen connecting the dates of one’s life and death, signifying life running its course between them

The artist first gained international fame in 1972 at Documenta 5 in Kassel with L’Album de photos de la famille D, an installation made up of a friend’s family photos. Everyday moments from a middle-class existence, they could have been images from anybody’s family album. In 2015, Boltanski reused the same images in La traversée de la vie, printed on cloth veils as though faded with time – one of the pieces on display at the Marian Goodman Gallery.

He avoids talking about his own background in his works – on the contrary, he created a made-up childhood early in his career. But he admits, ‘At the beginning of an artist’s life, there is always a trauma.’ His was historical: the war that forced his Jewish father into hiding under the floorboards of the family home in Paris from 1943-44. Boltanski was born a few weeks after the city’s liberation. His earliest memories are of family friends, survivors of the Shoah, telling their terrible stories. Even after the war, his family lived in fear. ‘I never saw my dad walk alone in the street. I was 18 before I walked alone for the first time. We lived in a big house, but we all slept in the same room.’ Boltanski stayed home from school. When he was 14, his older brother told him he could draw, and that was the moment he decided to become an artist.

His creations rarely make direct reference to the Holocaust, but its presence is often felt. The arbitrary nature of man’s existence inspired works such as Personnes (2010), where a mechanical claw grabbed at random articles from a mountain of used clothing, or The Wheel of Fortune at the 2011 Venice Biennale, where a machine haphazardly selected individual pictures of newborn babies, life’s essential lottery system laid bare. Boltanski, who is married to artist Annette Messager and has no children, keeps some of the baby photos on a wall in his studio, their round bald heads not unlike his own. Leaning against another wall is a board with the dates 1907-1989. He says it is a portrait of his mother: ‘Life is the little dash between those two dates.’

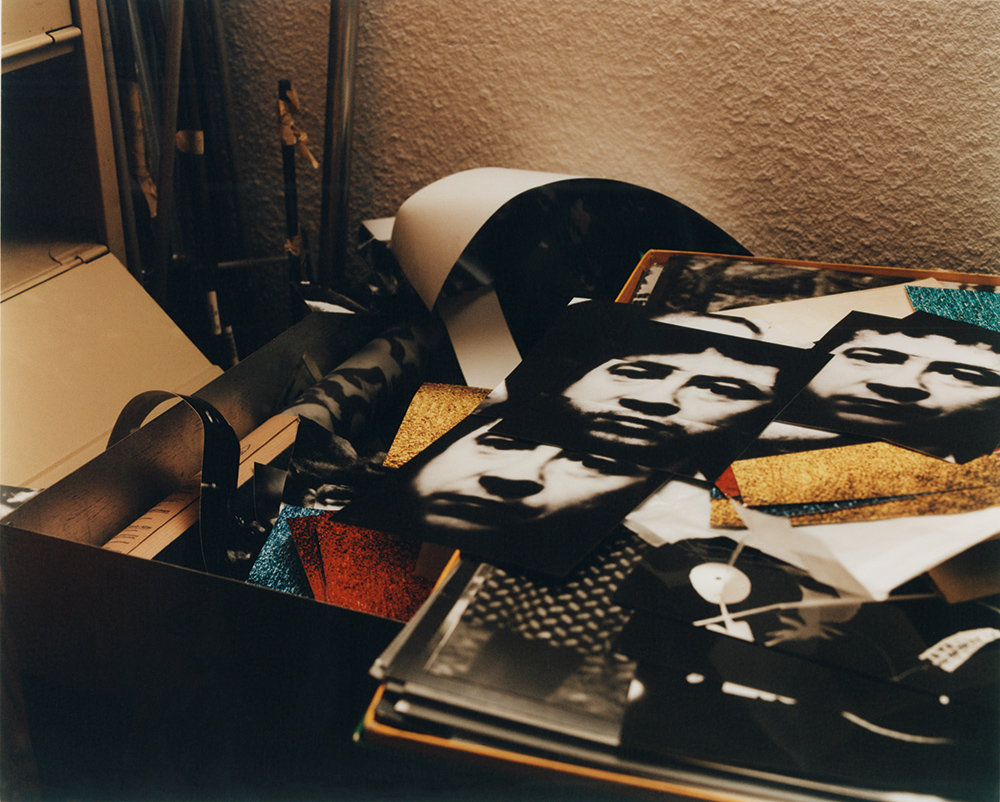

Photographic portraits of Boltanski, which he often uses in his works, such as Etre à Nouveau and Entre-Temps.

Despite the darkness in his work, Boltanski insists he is joyous. He points to his belly as proof that he likes to eat, drink and socialise, and he loves exhibiting in places like Bologna, where he can find a favourite dish. ‘I think that the fact of talking about all this makes you feel better,’ he muses. As he gets older, some of his installations have become more personal – Last Seconds, for example, is a digital counter that will stop ticking out the seconds the moment he dies. And though he claims not to be religious, certain of his works have started to explore what comes after we depart.

In recent years he has created installations in nearly inaccessible places, such as Chile’s Atacama Desert, where clear skies make for some of the world’s best stargazing and Pinochet buried political prisoners in mass graves. Here, Boltanski planted 800 Japanese bells on metal stems in the ground, like tiny souls, in the same arrangement as the stars on the night of his birth. He named it Animitas, after roadside memorials to the dead. He has repeated the exercise at three other sites: on the island of Teshima, overlooking the Dead Sea, and on Quebec’s Île d’Orléans. Videos of each, filmed from sunrise to sunset, will be all that remains after nature destroys the works.

Boltanski says that 80 per cent of the art he now produces will disappear, but he cares more about the idea behind an artwork than the physical thing, what he calls the ‘myth’ over the ‘relic’. Last year, in a remote part of Patagonia, he created Misterios, large horns that create sounds like whale calls when the wind passes through them. ‘Maybe, in a hundred years, my name will be forgotten, but someone will say there was a man who came here and talked to whales.’ He hopes people will play his works like music after he is gone. Now Boltanski wants to make a film about mayflies, ephemeral insects that come into the world, flutter around for a few hours, then die, like Macbeth’s poor player strutting his hour upon the stage. ‘That’s us, our lives,’ he says, flapping his hands for a moment.

A version of this article originally featured in the April 2018 issue of Wallpaper* (W*229)

An element from Boltanski’s Prendre la Parole installation

ADDRESS

Marian Goodman Gallery

5-8 Lower John Street

London W1F 9DY

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Amy Serafin, Wallpaper’s Paris editor, has 20 years of experience as a journalist and editor in print, online, television, and radio. She is editor in chief of Impact Journalism Day, and Solutions & Co, and former editor in chief of Where Paris. She has covered culture and the arts for The New York Times and National Public Radio, business and technology for Fortune and SmartPlanet, art, architecture and design for Wallpaper*, food and fashion for the Associated Press, and has also written about humanitarian issues for international organisations.