Wang Shu on modern Chinese architecture

Wang Shu, Pritzker Prize-winner and co-founder of Amateur Architecture Studio, talks modern Chinese architecture with Wallpaper* China editor Yoko Choy, following the pair’s contributions to Beauty and the East, a new book published by Gestalten

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

A new book by publisher Gestalten, Beauty and the East, explores contemporary Chinese architecture. The title charts the last two decades of ‘wild architectural experimentation' across China and celebrates homegrown talent and new designs that challenge the norm. Blending past and present, within the country and beyond, Chinese architects have been prolific in providing eye-catching and thought-provoking works. Celebrated Hangzhou-based architect Wang Shu, winner of the 2012 Pritzker Prize and co-founder (together with his wife, Lu Wenyu) of Amateur Architecture Studio, has contributed a preface, while Wallpaper* China editor Yoko Choy is behind the book's introduction.

Here, the two discuss the book's themes, and Wang offers his valuable insights into China's evolving architecture scene.

Yoko Choy: At the beginning of the preface, you wrote, ‘There is probably not a single Chinese architect who has not become a devotee of modern architecture after studying French master Le Corbusier's collection of essays Vers une Architecture (Towards a New Architecture)'. Architecture in China has been developing rapidly over the past few decades; in your opinion, what is the ‘new architecture' in a Chinese context and how will it develop in the future?

Wang Shu: The question should be seen from multiple perspectives, especially since the ‘new architecture' that we refer to nowadays is quite different from the one we were exposed to 20 to 30 years ago. At that time, we were determined to pursue something extremely new and disruptive of the status quo because we were so dissatisfied with the reality then.

One of the typical debates among architects from as early as the 1930s, as I recall, was about whether we should add a traditional Chinese roof to a new building. These debates are still ongoing, reflecting conflicting values between tradition and modernity. However, I believe the most crucial and urgent question for Chinese architects is a matter of spatial typology. The typology determines the relationship between culture, lifestyle and space. The 20th century was a turbulent one for China, during which society experienced drastic changes under an extreme ideological background, including even traditional family life. The architecture built at that time was merely copied from the West. As a result, some architects came to the conclusion that all typologies from the past were no longer relevant to the pursuit of ‘new architecture'. I believe that an investigation of architectural typologies in a contemporary Chinese context is the starting point for any further development in our current architectural practices.

Beauty and the East is published by Gestalten

YC: You pointed out that ‘[Chinese] architects are ideological and exploratory by nature, but the inadequacy of construction quality has been an arduous challenge'. Today we indeed see a lot of ‘photo-architecture' – designs that look perfect in photos but less so in reality. What's your opinion in that regard?

WS: Architectural education in China is heavily influenced by Western schools. I think that in some Western schools, the way architecture is taught can be problematic as neither the students nor the educators are given enough opportunity to practise and perfect their craft; the curriculum is thus very much focused on concepts and theories. The problem with copying the Western educational model is that the reality in China is different – a fresh graduate architect usually requires years of training as an apprentice before being put in charge of a project, yet in China, as demand is ever-growing, opportunities are abundant for even the least experienced professionals. Consequently, although they can make photogenic buildings, a lot of details are left out of the bigger picture.

China's architectural education should be aimed at our special situation. In my role as an educator [Wang is the head of the faculty of architecture in the Chinese Academy of Art in Hangzhou], our students learn to work with materials with their hands before learning abstract theories, because ideas that cannot be executed are worth nothing; in fact, this methodology also reflects the essence of the ‘craftsmanship' in the Chinese architectural tradition, a knowledge system that is built around materials combined with artisanship.

There is also the emergence of an architectural tendency in China that can be called ‘decorative architecture' or ‘scenic architecture' – something more of a theatrical expression than an architecture expression. This can bring about a quick delivery; however, in consequence, while the buildings will have a nice-looking, modern façade, the inside will be full of problems.

This leads architects with a more reflective approach to question the way that things should and could be done properly in China. For example, to imitate the European way – the so-called high-tech architecture – needs highly industrialised processes that actually can't be done in a pragmatic, profit-driven China that pursues short-term benefits, as no one is willing to do such time-consuming and costly projects. But does it mean that China cannot produce good architecture? I think good architecture can be created in all kinds of conditions. There is a saying central to Chinese philosophy, ‘suit one's measures to local conditions'. This is to say that to produce good architecture, architects should pursue methodologies that adapt to local constraints and conditions in the most simple and straightforward way.

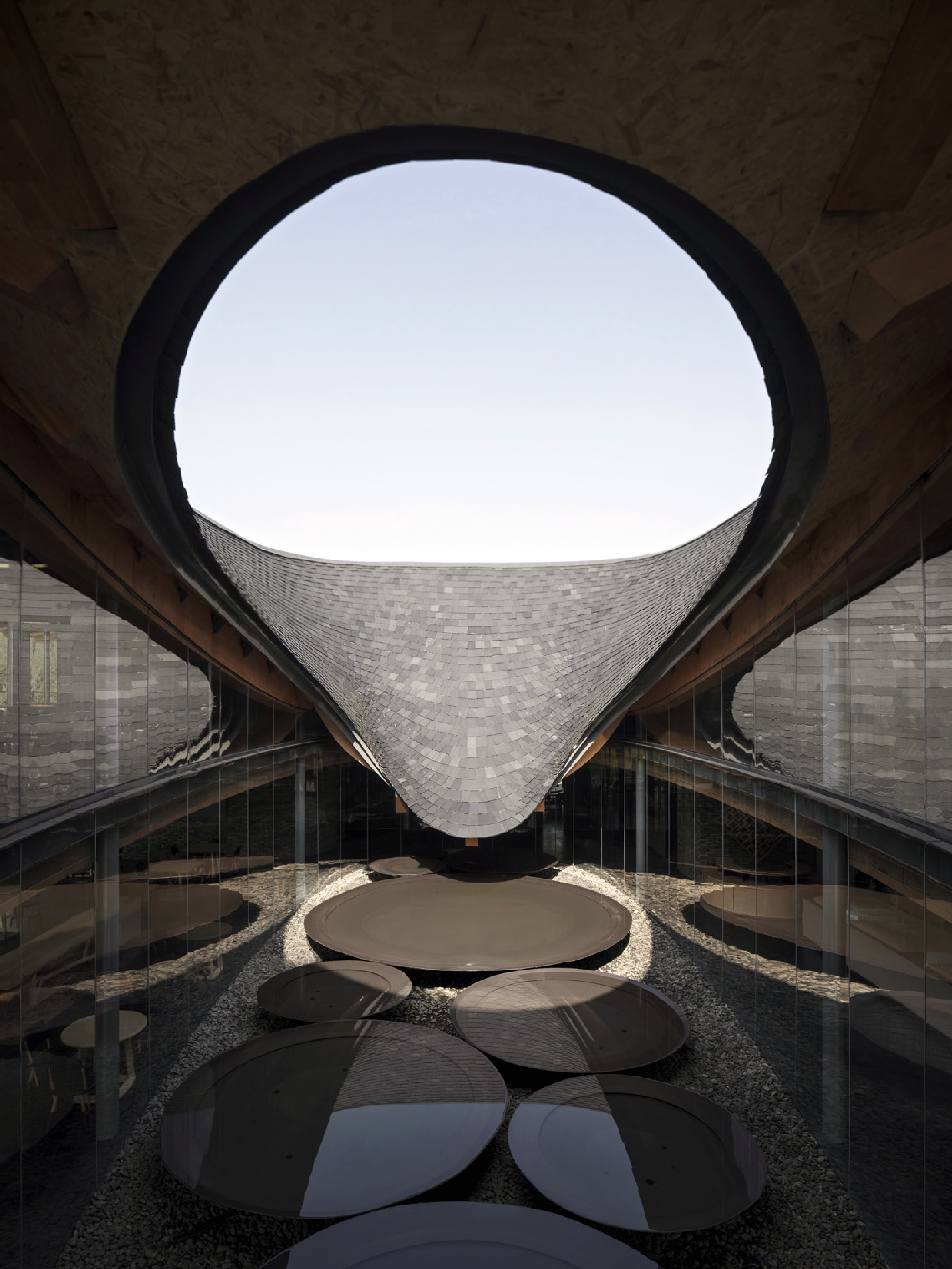

Capsule Hotel and Bookstore, Jinhua, 2019, Atelier Tao+C.

YC: There was this famous rule of your studio that you would only take one project each year.

WS: Before 2012, we had a rule that, without exception, we would only take one project each year. Since I was awarded the Pritzker Architecture Prize, society does expect me to create more and contribute more. So since then, we’ve increased our quota to two projects a year. In China today, in our society’s special circumstances, it takes great energy and time to perfect a project.

YC: Is this also the reason why the studio rarely takes commissions from outside of China?

WS: That is a whole different story. Since our way of doing architecture is deeply connected to traditional Chinese architectural craftsmanship, it would be hard to carry it out in the way we want outside of China. Up until now, we have accomplished very few projects abroad – we once built a bus stop in Austria, and recently finished a space in a museum in Berlin, both of which were collaborations with local carpenters.

It would be more sensible for us to collaborate with countries in the Global South – perhaps in South-East Asia, South America and Africa – because our cultures share a similar connection to nature, and we have a similar approach to architecture. This is to say that our consideration is not purely about practising abroad but is also concerned about the difference between Eastern and Western civilisations – our ways of architecture have been established under tremendous differences in culture and social constructs. Modern Western architecture – in countries in Europe, the US and also Japan – is a completely industrialised and artificial system, which draws a clear boundary between man and nature. In China, traditionally, our approach is more nuanced and doesn’t distinguish people from nature. Hence, it is not simply a comparison between tradition and modernity.

Jishou Art Museum, Jishou, 2019, Atelier FCJZ

YC: Chinese architects are constantly discussing the impact of architecture on society and the environment. From the perspective of environmental protection and sustainable development, it is only reasonable to produce architecture of high quality and great longevity. But it is not the case yet in China.

WS: I think the situation in China now is a result of a whimsical mix of Chinese and imported culture. Most of our buildings look like merely temporary structures and they are likely to be torn down and rebuilt in a decade or so. On one hand, this reflects a utilitarian, profit-driven way of thinking that renders architecture primarily a commercial product of the burgeoning market economy.

On the other hand, again, it’s about Chinese architectural traditions. Traditional Western architecture was created with materials like stone to last a thousand years, the idea of longevity and sustainability is embedded in the process. Chinese architecture, however, employs materials like soil and wood, which are not supposed to last forever; using seemingly fragile and short-lived materials, it builds a resilient and flexible natural system that is constructed to achieve a kind of cyclical endurance. As a good example, the wooden structure of a Tang Dynasty [618 to 907] building is prefabricated. Prefabrication means that if a piece of wood breaks, it can be replaced to maintain the integrity of the structure. We can still find these buildings today, although there might only be 20 or 30 per cent of the materials that are from the initial building while the rest are replacements that happened along the way.

The pursuit of sustainable development itself is sometimes paradoxical in the Chinese context – to achieve energy efficiency in buildings requires an insulating layer in the wall, for example, but the natural materials used in traditional Chinese architecture must be ventilated inside and out. Consequently, the pursuit of energy efficiency would eliminate Chinese traditions. So, is the Western model of energy efficiency suitable for China? Chinese architects must think independently from the Western system to place the future of architecture in the framework of localised sustainable development.

YC: Chinese architecture and architects are receiving a lot of attention at the moment. Taking into account China’s different cultural background that you’ve discussed, what kind of influence and contribution, in your opinion, could Chinese architects bring to the global architecture community?

WS: Chinese architects should reflect on their role in an era full of cultural conflicts and the current circumstances of the environmental crisis to decide what values and contribution they could make on a global scale. One of the main subjects would be to establish a contemporary architectural ecosystem that allows us to coexist with nature and step away from the overly artificial and industrial state of affairs. This is what we should be discussing: not simply Chinese cultural identity at face value. Many people tend to simplify Chinese culture into decorative symbols and neglect to address essential philosophical discussions about our core values.

Harbin Opera House, Harbin, 2015, MAD Architects

Shelter – The Mirrored Sight, Kaili, 2016, One Take Architects

Inkstone House OCT Linpan Cultural Center, Chengdu, 2018, Archi-Union Architects.

Twisting Courtyard, Beijing, 2017, Archstudio

Wuyuan Skywells Hotel, Shangrao, 2017, AnyScale

UCCA Dune Art Museum, Shanghai, 2018, Open Architecture

Long Museum West Bund, Shanghai, 2014, Atelier Deshaus

INFORMATION

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Yoko Choy is the China editor at Wallpaper* magazine, where she has contributed for over a decade. Her work has also been featured in numerous Chinese and international publications. As a creative and communications consultant, Yoko has worked with renowned institutions such as Art Basel and Beijing Design Week, as well as brands such as Hermès and Assouline. With dual bases in Hong Kong and Amsterdam, Yoko is an active participant in design awards judging panels and conferences, where she shares her mission of promoting cross-cultural exchange and translating insights from both the Eastern and Western worlds into a common creative language. Yoko is currently working on several exciting projects, including a sustainable lifestyle concept and a book on Chinese contemporary design.