This modern Clapham house is nestled indulgently in its garden

A Clapham house keeps a low profile in south London, at once merging with its environment and making a bold, modern statement; we revisit a story from the Wallpaper* archives

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

It is often the bolder, most unorthodox solutions that prove the most successful, and architects in London should know. Over the years, the capital’s swelling housing needs have pushed many a practice to test the limits of their inventiveness. This is also the path architect couple Deborah Saunt and David Hills of DSDHA chose for their home, a move that resulted in a bespoke house for their family of four, but also an enjoyable professional challenge. Saunt explains, ‘The project asks how a city like London might provide new housing within its fiercely defended, low-density backlands, close to the historic centre, while preserving neighbourly amenity.’

Step inside this elegant Clapham house

The hunt for the pair’s ideal bolthole started in 2007 and led them to an unconventional, hidden site in Clapham Old Town, a roughly 12.5m x 20m patch of land linked to a generous, street-facing townhouse. It offered great connections and was close to their new studio in Vauxhall. Living in a traditional three-storey terrace not too far away, the pair needed a change and if the right property didn’t exist, then they would have to build it. ‘We also hoped that we might be able to test out some of our more radical ideas,’ says Saunt. ‘Over time it became a case study for some of our wider-reaching ambitions. If we were asking other people to live in new ways, surely we had to do so ourselves, if at all possible.’

The site sits within the townhouse’s back gardens, amid mature trees. It was never advertised for sale, but the pair approached the owner to discuss their idea. ‘On a practical level, we did not choose the site,’ says Saunt. ‘Rather, we generated an opportunity speculatively by directly approaching several owners of potential sites nearby. So the site chose us in the end.’ The plot came with a small cottage, which the couple sold on to friends.

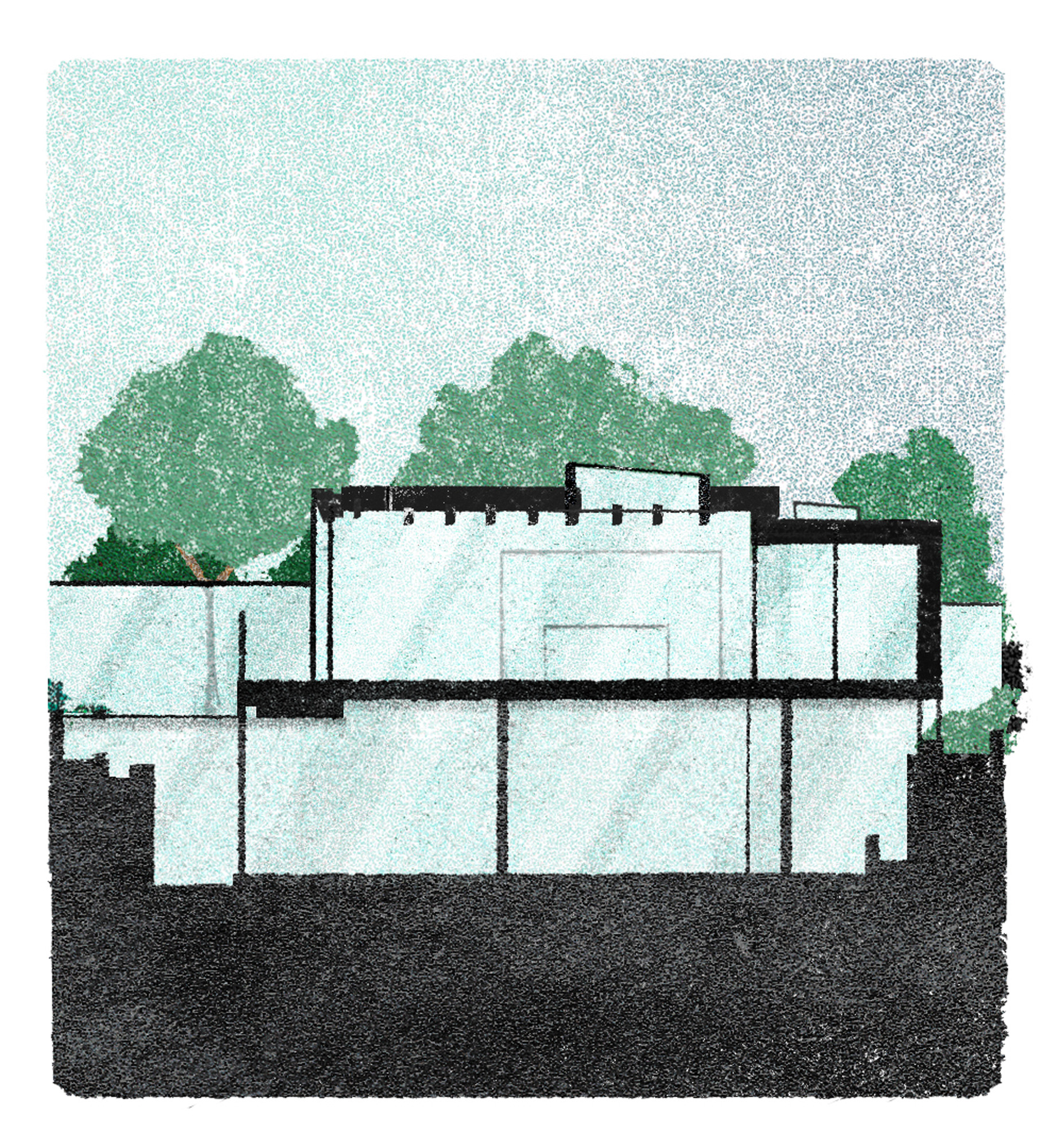

Of course, a bold approach doesn’t necessarily mean showy. The new build is aptly named Covert House, as it is low and completely invisible from the street. Set back behind a terraced row of houses, it has a discreet presence among the surrounding gardens and rear façades. This was critical to the project, in the heart of a conservation area. ‘We had to establish that the local authority’s planning policies were being met, and certain limits had to be agreed with the planners to enable the project to proceed,’ recalls Saunt. ‘Height limits were established, which means the building has a stepped roof line in section, so it’s lower close to garden boundaries.’ The plot’s leafy character also had to be maintained, a requirement satisfied by 12 new trees surrounding the house.

Raw concrete walls in the living and dining area on the upper level

The volumes and ‘transitionary’ elements between inside and outside were meticulously planned, so that the new building reads more as a ‘pavilion set within a garden’. Polished and reflective steel-clad chamfered reveals around the upper floor openings help light to flow in and also create a visual dialogue with the garden. The structure is made out of cast concrete – in some parts ‘raw and unfinished’, in others ‘precise and highly articulated’ – which is rendered white in circulation areas, adding to the structure’s overall lightness.

Covering 150 sq m of living space, the house features a typical inverted layout. The slightly raised ground-floor entrance leads to a small hallway and through to the main living space, which contains an open-plan kitchen, living and dining area. Large skylights cutting through the roof and a fully glazed south façade food the interior with natural light, while cleverly concealed storage contributes to the uncluttered and airy feel.

A section shows the house cut into its garden site, with the lower level below ground and the upper level decreasing in height towards the property’s boundaries

The open views accentuate the indoor/outdoor bond. ‘The boundaries between inside and out are blurred purposefully,’ says Saunt. ‘A sense of linking to nature and the organic is present throughout.’ This approach to hybrid spaces, which is a recurring element in DSDHA’s work, finds some of its roots in Saunt’s background and her early childhood years, spent in Australia and Kenya, ‘caught between inside and out’.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

A sweeping, sculptural white concrete staircase takes the visitor down to the lower floor. This level is partly sunken and within it nestle the master bedroom, two children’s bedrooms, a bathroom, a television lounge and a piano alcove. Light wells enhance the sense of space. A colour palette of white and concrete-grey is in keeping with the house’s light and discreet, monochromatic theme.

Winding staircase

Covert House answers many of the ‘hypotheses’ set by the architects at its conception. It is an exploration into contemporary domestic space; an exercise in integrating sustainability in design; proof of their commitment to craft; and a good case study for London’s housing debate. ‘It was designed with a few simple rules,’ adds Saunt. ‘To use the most sustainable design principles possible while deploying a limited material palette, yet creating a sense of domesticity within a concrete armature that does not disturb its sensitive setting.’ Its design is precise and efficient, ultimately producing a domestic haven, only a stone’s throw from central London.

A version of this story was first published in Wallpaper* November 2014

Ellie Stathaki is the Architecture & Environment Director at Wallpaper*. She trained as an architect at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece and studied architectural history at the Bartlett in London. Now an established journalist, she has been a member of the Wallpaper* team since 2006, visiting buildings across the globe and interviewing leading architects such as Tadao Ando and Rem Koolhaas. Ellie has also taken part in judging panels, moderated events, curated shows and contributed in books, such as The Contemporary House (Thames & Hudson, 2018), Glenn Sestig Architecture Diary (2020) and House London (2022).