Inside Kazakhstan’s Soviet-era Tselinny cinema – now a hub for contemporary culture

Tselinny Center of Contemporary Culture, a modernist landmark redesigned for its new purpose by Asif Khan, gears up for its grand opening in Kazakhstan

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

When the project to transform Tselinny, the 1960s modernist Soviet cinema in Almaty, Kazakhstan, into a multidisciplinary arts venue first started taking shape, seismic engineers initially recommended that the building be completely demolished. 'The seismic approach in the 1960s was very different to what it is today,' explains architect Asif Khan, who worked on the project closely with his wife, Kazakh architect Zaure Aitayeva, of the contemporary engineers’ concerns. Looking at the building anew, 'there was a great deal of fear that if there was a major earthquake in Almaty, like there was back in 1911, the building would just fall down'.

Fortunately, Khan and the wider team behind the project were able to convince state research and design body KazNIISA that the building was worth saving – and the journey towards creating the first bricks-and-mortar home for the Tselinny Centre of Contemporary Culture began.

Tour Asif Khan's Tselinny Center of Contemporary Culture in Kazakhstan

Founded in 2018, the privately funded institution aims to provide a national and international platform for (and archive of) Kazakh and Central Asian art in a country where state support for the arts is limited and in 'a city where there are a lot of artists but very few arts venues and galleries', explains the centre’s director, Jamila Nurkalieva.

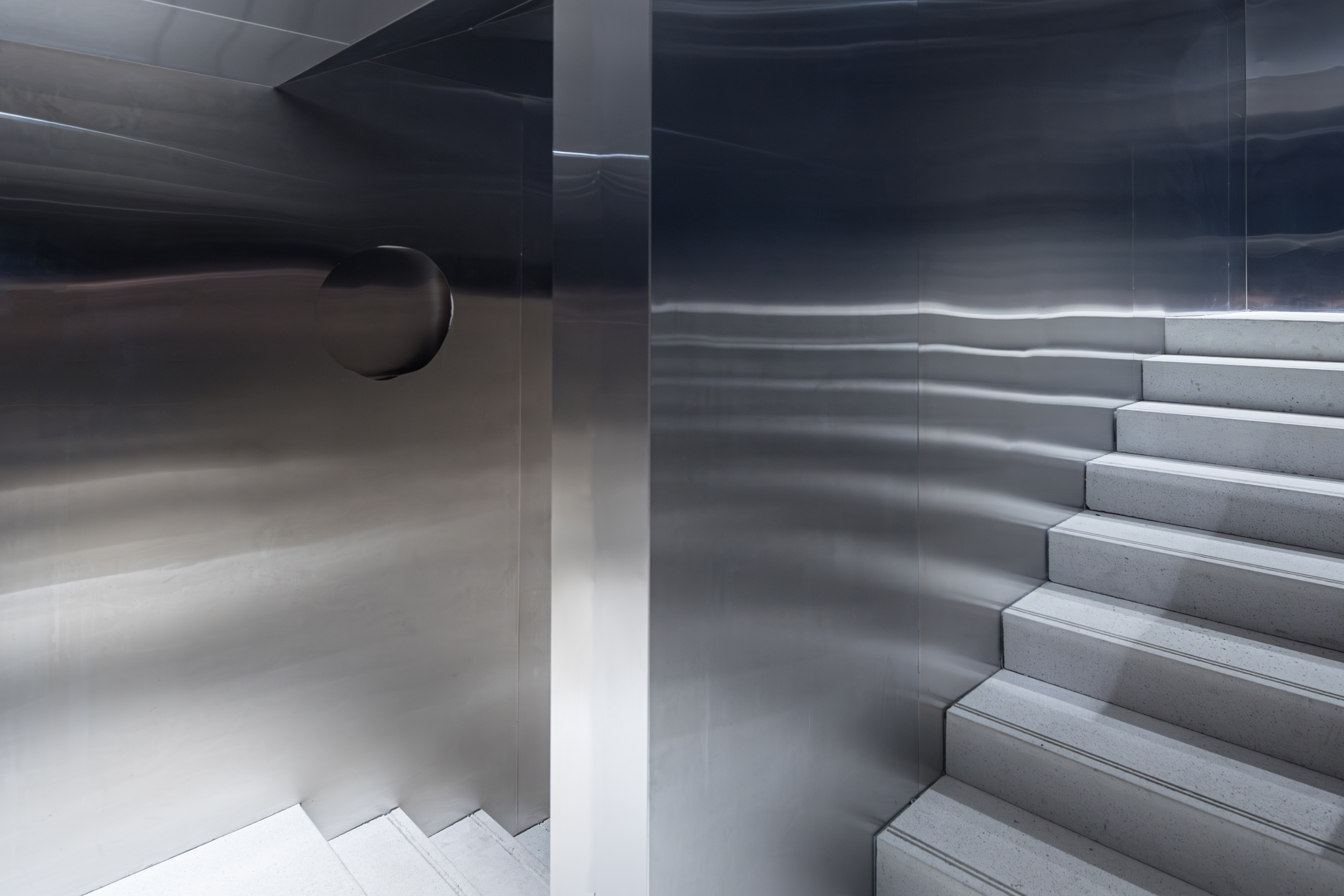

The architects started by stripping back the building to the 18m-tall auditorium at its heart, reinforcing it internally with a steel frame but keeping the original roof. Everything around the auditorium had to be rebuilt, but this was done within the original footprint of the building. Retaining the structure's original size and height was important, as the cinema is a familiar and significant local landmark. 'It was where you would bring your first date,' says Khan, 'and in fact the founder of Tselinny, Kairat [Boranbayev], brought his wife Sholpan here for their first date in 1987.'

More recently, in the early 2000s, the cinema was converted into a hybrid venue with a nightclub. 'They served sushi and pizza and had photo booths,' says Nurkalieva. 'It was very successful and a focal point of the city in what was then a relatively recently independent Kazakhstan.'

It was during the building’s nightclub era that the monumental 42m-long sgraffito by Russian-born artist Evgeny Sidorkin, which adorned the large glazed public foyer of the original building, was covered up behind drywall. 'They had put in a steel frame to create a mezzanine and divided the sgraffito into several pieces, damaging it permanently,' explains Khan. The Tselinny team worked with local restorers and archival photographs to remake the sgraffito, cleaning off the layers of paint that had been added to the piece over the years and installing it in what is now a column-free and airy foyer. 'We decided to leave the scars visible so all the areas that were damaged in the 2000s and reconstructed are in white and distinct from the original,' says Khan.

Like many things in the region, the history of the Tselinny cinema is a rich and complex one. Opened in 1964, it was named after a colonial Soviet agricultural campaign – Tselina (or Virgin Lands), initiated by Nikita Khrushchev in 1953 – that saw hundreds of thousands of volunteers from elsewhere in the Soviet Union brought in to appropriate the traditional nomadic homeland of the Kazakh people – the steppe – and transform it into farmland. 'It shaped modern Kazakhstan in dramatic ways,' says Khan, 'and was the nail in the coffin of a nomadic way of life that had endured for thousands of years.' The decision to keep the cinema’s original name is part of an intentional attempt to 'deal with and repair these past and traumatic histories and attempt to move forward without the baggage of the past'.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Another way of dealing with the building’s and region’s history was to reconnect the site with its indigenous past. This can be seen on the new concrete envelope of the foyer building, which is covered in petroglyphs that reference both the ancient symbols and forms found in Sidorkin’s mural and the geological markings found across Kazakhstan. Most of the petroglyphs are carved into the wall and atmospherically illuminated at night; others are punctured into the building and become enigmatic-looking windows.

The region’s pre-colonial past is also referenced in the gently undulating ‘wall’ of white-painted steel fins that covers the building’s glass façade and invites people in. Khan and Aitayeva both speak of nomadic cosmology and the spirits Tengri (sky) and Umai (earth) as the inspiration for this cloud-like threshold or ‘device’. 'We wanted to bring a mythological force from ancient memory into the building so that the past and the future, the earth and the sky, could confront one another,' says Khan. 'The cloud softens and diffuses the rigid frame of the original building that represents colonial power.'

One of the most transformative changes to the building is arguably also the most practical. Thanks to the team’s removal of the original steps up to its entrance and 'digging down until we reached a universal level', the new Tselinny has been made far more accessible and welcoming and is now visually connected to the external landscape and street. The entire ground floor is on one plane, something Khan likens to the horizontality of the Kazakh Steppe.

At its heart is the original auditorium, a space that originally held over 1,500 seats. This vast space will host everything from performances, such as theatre and music, to exhibitions and roundtables, while more intimate shows will be held in the ‘capsule’ gallery in one of the foyer’s wings. Elsewhere on the ground floor, there’s a glass-fronted café and bookshop and a tearoom at the back that, when opened, will look out onto St Nicholas Cathedral and the park beyond.

Upstairs, there is a learning ‘atelier’ and offices, and on the top floor, a yet-to-open rooftop restaurant that looks out onto the surrounding snow-capped mountains. Both the restaurant, which is named after Sidorkin’s wife, Gulfairus ('probably the most important Kazakh artist that has ever lived', says Khan), and the café are designed by local female-led architectural practice NAAW.

The café features earthy organic tones and a communal burnished-stainless-steel table designed in a river-like form that echoes the fluidity of the sinuous outdoor landscaping, which in turn references the rivers in and around Almaty. It’s another nod to ancient Kazakh landscapes in a layered project intent on unearthing and honouring deep histories – a project that reclaims the past in order to embrace the future.

Giovanna Dunmall is a freelance journalist based in London and West Wales who writes about architecture, culture, travel and design for international publications including The National, Wallpaper*, Azure, Detail, Damn, Conde Nast Traveller, AD India, Interior Design, Design Anthology and others. She also does editing, translation and copy writing work for architecture practices, design brands and cultural organisations.