The diverse world of Belgian embassy design – 'style and class without exaggeration'

'Building for Belgium: Belgian Embassies in a Globalising World' offers a deep dive into the architecture representing the country across the globe – bringing context to diplomatic architecture

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

In the introduction of his new book on Belgian embassies, Bram De Maeyer starts by citing a seemingly bland bit of bureaucracy from 2016, when the Belgian Ministry of Foreign Affairs decided to move its embassy to a new location in Washington, DC. 'An embassy is a building that represents a country abroad,' begins the edict-like public tender to renovate the premises it had just purchased for its American mission, before continuing, 'Through this building a country shows itself to the outside world.'

Indeed, as De Maeyer wittily argues, embassies are the most tangible expressions of a nation’s presence abroad: material manifestations of identity, policy, and self-perception. 'Therefore,' the Foreign Ministry's tender continues, 'it is important that Embassy buildings show a certain style, class without exaggeration, as they are in fact a visit [sic] card of the country in question.'

Cover image - Main entrance of the Belgian ambassadorial residence in New Delhi with its exposed brickwork and lingam-shaped volumes, 1985 (© Massachusetts Institute of Technology, courtesy of Peter Serenyi).

Explore the finest Belgian embassies and their architecture

It is De Maeyer’s choice to hone in on details such as the use of almost incongruously subjective adjectives like ‘style’ and ‘class’ by Belgian officialdom that makes his work so unique. It opens the door to a thorough examination of both the post-war statecraft and diplomatic architecture of this small Western European nation. That cited public tender from 2016 makes it very clear that for the client (the Belgian State itself, no less), this [Washington DC] 'embassy project was by no means a mundane commission,' De Maeyer argues.

A post shared by DAG Museums (@dag.museums)

A photo posted by on

Pivotal to the author’s method is the constant contextualisation of embassy building design as a whole, globally. In many ways, an embassy is never, or at least should never be, ‘a mundane commission’. It is through rich case studies in America, Poland, Australia, Brazil, Japan, the DRC and perhaps most spectacularly, in India with the New Delhi embassy (Satish Gujral, 1980-83) that De Maeyer successfully makes the case that Belgium has consistently and decidedly invested in architecture as an act of international self-representation.

'An embassy should never be a mundane commission'

De Maeyer

The Flemish export office of the Belgian Embassy in Tunis

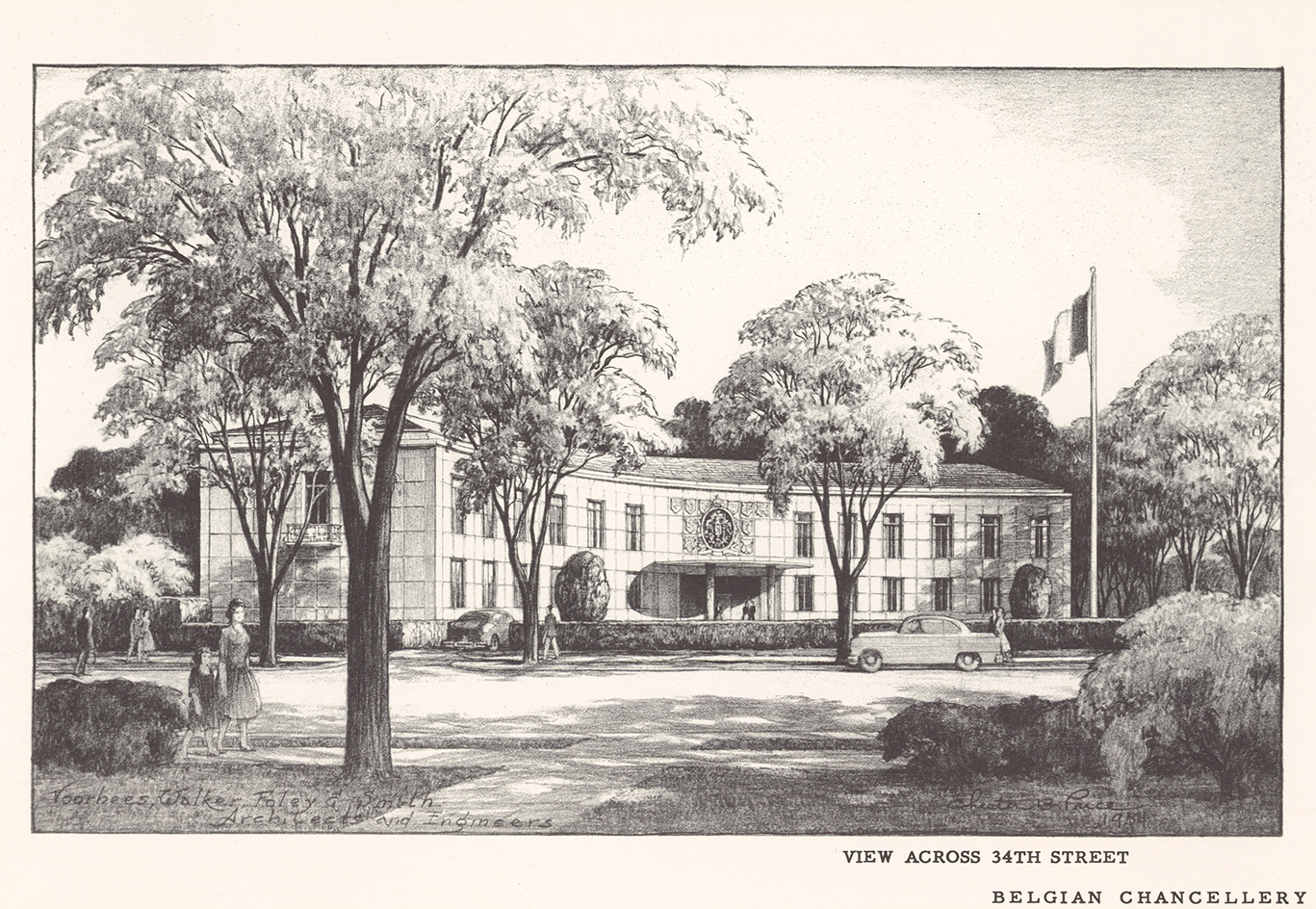

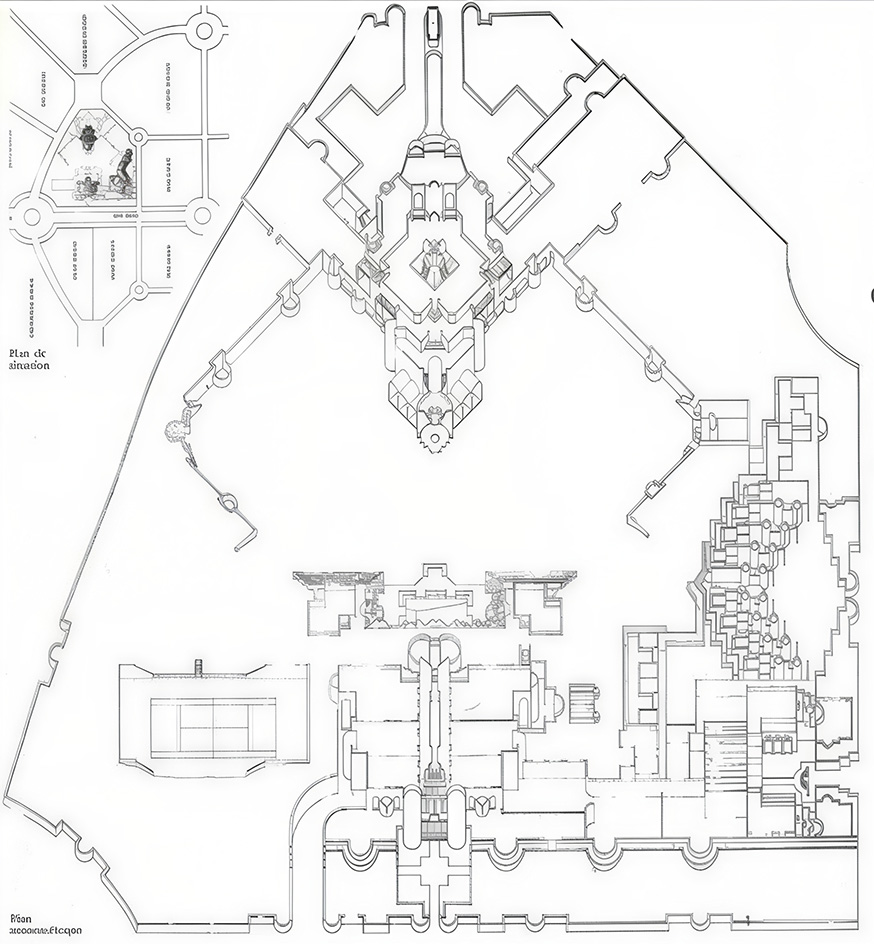

As a recipient of American aid through the Marshall Plan and as a founding member of NATO, understandably, Belgium’s diplomatic building machine paid massive attention to Washington, DC, in the immediate post-war years. But De Maeyer reveals the remarkable impact of Baron Robert Silvercruys, who was appointed as Belgian Ambassador in 1945 and whose intrepid gusto in selecting sites, architects, materials and artworks led to an outsize Belgian presence in a crowded centre of world diplomacy.

Fresh in the post, the Baron managed to convince the war-torn and cash-strapped Belgian State to acquire the palatial Hôtel particulier-style residence at Foxhall Road. De Maeyer cites an article in the Washington Times Herald at the time: 'Belgium is in good shape; Silvercruys lives in one of the most magnificent estates in Washington.' When it came to Belgium’s Chancery building, with the help of his chauffeur, Silvercruys scanned the local real estate market and chose a prime 5000 sq m plot next to Edwin Lutyen’s opulent British Ambassador’s residence. The book delves into the fascinating science of the geographical positioning of embassies within the world's capitals. Location, location, location, only on a diplomatic scale.

A post shared by Adam Nathaniel Furman (@adamnathanielfurman)

A photo posted by on

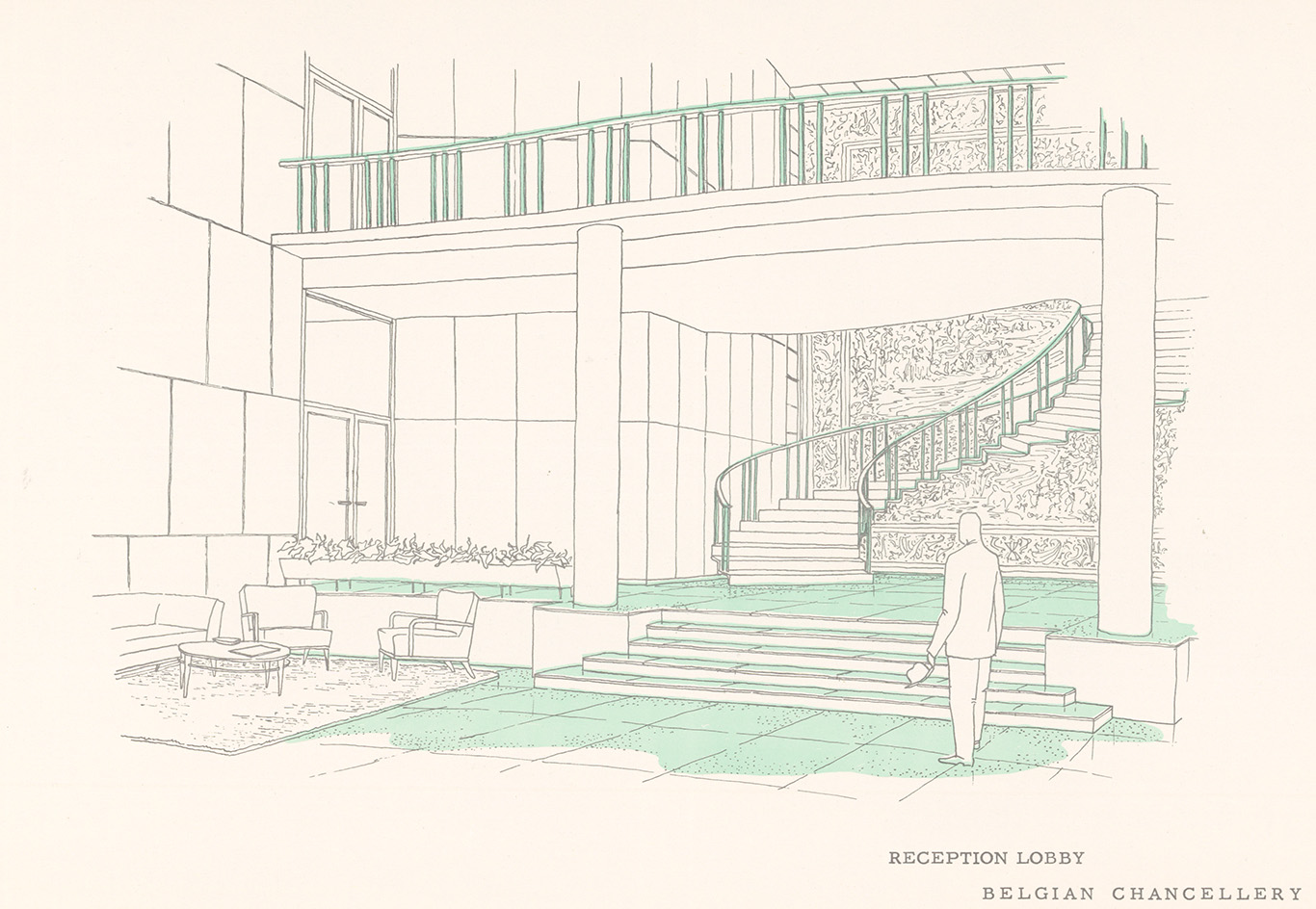

For De Maeyer, however, as much representational force resides indoors; 'As the metaphorical home of the nation abroad, embassy interiors tend to be carefully orchestrated decors where material objects serve as instruments of identity-building and national representation.' At the Washington Chancery, Silvercruys selected Belgian marble, Congolese timber and a monumental tapestry linking Belgian and American histories and combined them with the height of midcentury modernist craftsmanship to produce a carefully orchestrated whole.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

The Washington chancery, 1954

The book attests to the fact that these interior spaces, from Washington to Tokyo, are difficult to reconstruct. Documentation is scarce; photographs are often taken from grainy press cuttings of staged portraits, where interiors act as mere backdrops. Rooms and halls were routinely stripped, and furniture was unceremoniously disposed of, erasing the work of the informal interior designer, who was usually the ambassador’s wife, says De Maeyer, highlighting the ephemeral and often gendered nature of the material in question.

The book is all the more valuable as it gives a picture of embassies as liminal spaces between home and state, where hosting, ritual, and social choreography (often shaped by the ambassador’s partner) reveal diplomacy as something enacted through atmosphere as much as architecture.

The New Delhi embassy compound, undated

De Maeyer argues that Belgium’s embassies are especially intriguing in contrast to a weak public-building culture at home, where architectural ambition was often blunted by bureaucracy and political patronage. Abroad, by contrast, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs operated largely independently of the public works ministry, enabling a surprisingly bold and diverse body of work. This allowed a small, internally divided Belgium to present itself architecturally on the world stage. The clearest expression of this is the embassy in New Delhi, widely regarded as the jewel in Belgium’s global portfolio crown.

Designed by the artist-turned-architect Satish Gujral, the building is a sculptural, brick-clad composition that draws on local fortresses, traditional Hindu forms and regional craft traditions. Rather than exporting a recognisably Belgian aesthetic, the ministry granted Gujral unusual creative freedom. For De Maeyer, this openness is not accidental but strategic in the absence of a singular Belgian national architectural identity. The author likens asking ‘What is Belgian?’ to the opening of Pandora's box; the question only exposes linguistic and cultural fault lines. Abroad, therefore, Belgium’s strategy became one of adaptability, flexibility and trust in strong architectural voices.

The Chancery Lobby 1954

Despite this admirable built output, the book also tells the story of various challenges faced along the way. The positioning of an embassy – whether central or remote, monumental or discreet– is itself politically charged, a tension traced from Washington to its starkest expression in Kinshasa. The prominent positioning of Belgium's embassy in its former colony, the Democratic Republic of Congo, has made it hard to shed colonial symbolism.

Despite the bilateral and cooperative spirit intended (the building being shared with the Netherlands), the embassy became the target of an attempted attack during protests in January 2025. It is a reminder that diplomatic architecture operates within specific and evolving social and political landscapes. De Maeyer notes that the building was originally shaped by prestige politics, part of an architectural one-upmanship with France, whose own imposing embassy in Kinshasa sought to reaffirm French influence in the region.

More broadly, Belgium’s reliance on rented or adapted buildings and its lack of a fixed doctrine for embassy construction has produced an ad hoc policy driven by circumstance and individual actors. Crucially, De Maeyer frames this not as a weakness but as a quiet strength. Free from exporting a single national style, the book concludes, Belgium has repeatedly tailored its embassies to local contexts from Washington to New Delhi and beyond. It is this flexible, decentralised approach that is the unlikely key to Belgium’s architectural successes in the world of diplomacy.

'Building for Belgium: Belgian Embassies in a Globalising World (1945-2020)' by Bram De Maeyer, published by Leuven University Press, November 2025, buy on amazon.co.uk

David is a writer and podcaster working (not exclusively) in the fields of architecture and design. He has contributed to Wallpaper since 2022 when he wrote about the late, postmodernist architect and founder of the Venice Architecture Biennale - Paolo Portoghesi reporting from his home outside Rome. In 2024, David launched Arganto - Gabriele Devecchi Between Art & Design, a podcast exploring the life and legacy of this Milanese silversmith and design polymath.