Valie Export in Milan: 'Nowadays we see the body in all its diversity'

Feminist conceptual artists Valie Export and Ketty La Rocca are in dialogue at Thaddaeus Ropac Milan. Here, Export tells us what the body means to her now

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

In the 1960s, feminist artists were increasingly looking to express what it is to be female, in ways outside of a language dominated by men. For Valie Export in Vienna, and for Ketty La Rocca [1938 - 1976] in Florence, this meant exploring the potential of the body itself. For Export, the naked body became a medium for discovery - in work TouchCinema (1968) she invited viewers to touch her breasts through a box, her body the cinema screen and her audience the participators. For La Rocca, this same philosophy took shape through looking inwards. The X-Ray images of a skull in her Craniologie series (1973) are double-exposed with photographs of her hands, emphasising the need for both the mind and the body.

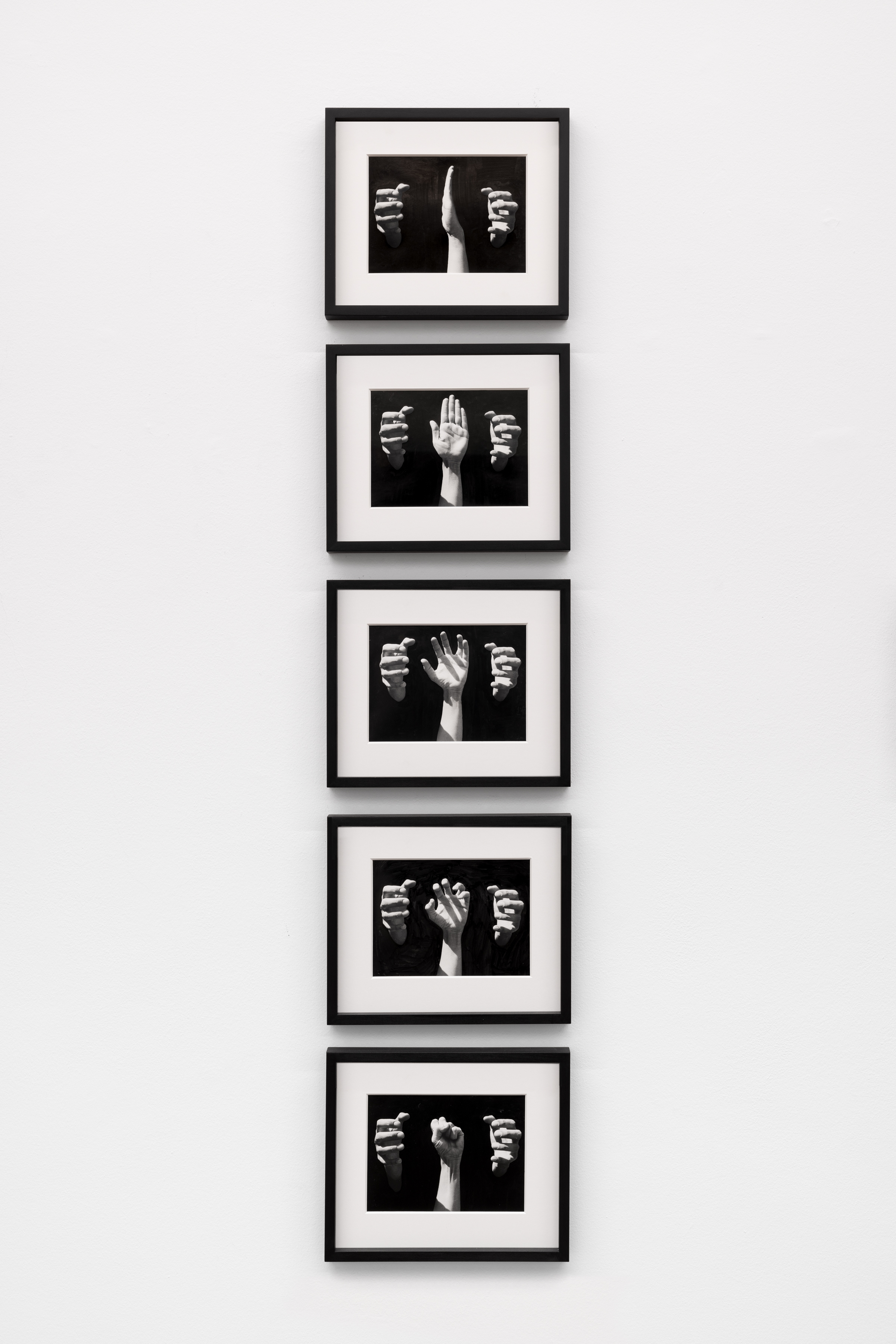

Ketty La Rocca, l'incauto, 1971

Although the two never met, their careers ran on parallel paths. Both confronted the patriarchal language in often controversial visual experiments; sometimes through a linguistic play, sometimes semiotic or sexual, but always with a sharp and defiant eye. It is fitting, then, that their works have now been placed in dialogue, with an exhibition at Thaddaeus Ropac Milan drawing works from both their portfolios.

Why now? ‘Nowadays we don't just see the female body, we see the body in all its diversity,’ says Export, who lives and works in Vienna. ‘We are now ready to accept that we also have so-called male attributes in our female bodies. The classification of male and female is no longer accurate. The prevailing politics, the restrictive politics, tells us that we have a female body and a male body, but that is a reduction to black and white and nothing more, because that black and white is easier to control.’

In both her work and La Rocca’s, this unequivocal thinking is teased into new shapes, with the language taking on new purposes and meanings. A shared retrospective has never felt more timely - here, Export tells us how it feels to revisit the work now.

Valie Export on art, power and the body

VALIE EXPORT–SMART EXPORT, 1967/70

Wallpaper*: What interested you most about placing your work in dialogue with Ketty La Rocca’s? Where do you see the most powerful intersections or divergences between your artistic languages?

Valie Export: When I got to know Ketty La Rocca’s work better, what struck me most about her was that she works with hands, that she works in particular with hands. I had once written in a text, ‘My hands are my identity.’ And I really felt that way: that my hands are my identity. They show age, they show gestures, they show movement, they show feelings. Hands are very expressive because they are so mobile. You can paint, you can strike. You can be tender, you can work with them. You can do all kinds of work with your hands. That's the most important thing. And that's what struck me most about her, that she also uses this physical medium, this bodily medium, as an organ of perception. That’s what made me want to engage with her more closely.

Both of you used your own bodies as central material. How do you understand the different ways you and La Rocca approached embodiment, gesture, and communication?

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

For me, my body was the most important medium; my body is also me. My body expresses who I am, expresses my identity, and that's what surprised me so much about Ketty La Rocca, or rather fascinated me, how she also expressed her identity through her body language, through her body – if you take the hand to represent the whole body. That surprised me so much and created such a connection for me. And hands are also a kind of connection. You shake hands; you give your hand away and you give your hand to someone else. Hands also have such a multifaceted meaning, as do gestures and touch. Hands have their own dialogue; they talk to themselves, but they also talk to others by touching them. By reaching out hands towards one another, they are also a form of object communication.

Valie Export, SYNTAGMA (film still), 1983

How do you feel the exhibition reframes La Rocca’s legacy in relation to your own, especially within the lineage of feminist and conceptual art?

La Rocca's legacy is an idealistic one. It is not a tangible legacy. She speaks with her hands, but this legacy cannot be grasped with the hands. It is an idea, and it takes you into a realm of its own, where I can also find myself, reflecting like a mirror, certainly with a living mirror screen. Not completely smooth, but lively, as if a mirror were constantly changing. That's how I see it, that's how it comes across to me and how I see it within feminist and conceptual art. Feminist art is conceptual art, that's very clear to me, but conceptual art doesn't have to be feminist, that's also very clear. But La Rocca puts it the way I've tried to, bringing both together, saying that feminism has a concept and it can also be expressed in conceptual art, but that the oeuvre or the main work or the main word is feminism. While I declared myself explicitly as a feminist, Ketty La Rocca didn’t align herself with the feminist groups that were in Italy at the time. But bringing the body into conceptual art as a subjective perspective is a feminist achievement.

Valie Export, Einkreisung, 1976/ 80

What emotions or memories did this exhibition bring back about the urgency and constraints of working as a woman artist in the 1960s and 70s?

It was a long time ago, and of course it stirs up emotions in me now, how hard it was for us, how we had to fight. How we really had to assert ourselves. But my memories are also linked to very positive developments. We found each other, we came together, we coined the slogan, “Women together are strong”. That's a very important slogan, which may have already existed in the 1920s, but then of course disappeared completely due to the wars, where the masculine was naturally the leadership principle. But we realised that there is no such thing as male and female leadership. There is human leadership. And where do we stand as human beings and what do we have as human beings? But our sociality, our place in society, which is of course now associated with various things, brings us society as women, not as females, but as women. And that, of course, has other effects and implications. And we need to be aware of that. We want to be women. We don't want to be just something, we want to be women. And I believe that young women and girls also know that this is what they want. But we don't want to fight, we want to work together towards a positive future for all genders.

Ketty La Rocca, Appendice per una supplica, 1972

How does this collaboration speak to your own ongoing mission of challenging power structures, both within art and society?

I have nothing against power. We need power. If we want to get things done, we need power. The question is, how do we define our power, or how do we find expressions of power that do not oppress others, but rather analyse and open things up? In the 1960s and 1970s, people said that women did not need power. I was always completely against that, because if we don't have power, we can't change anything. But the structures must be adapted to free speech or free thought. With all the information we have, which we receive every day, it's becoming increasingly difficult to express ourselves correctly, because we don't know the future and we can't influence the future through the many power structures we have, even if we have them or if they exist. That means we must, as I always say, be vigilant and analytical.

We opened up and launched this in the 1960s and 1970s. In the post-war period, it was very important to continue what had been happening for centuries before. Women have been doing this for centuries, or even millennia, and have also fought battles. It's nothing new. We just rediscovered it for ourselves, which was the right thing to do. But we have to keep reconquering these power structures. Ketty La Rocca fought for her cause and for herself during her lifetime, and through my work, which we’re now showing here, I want to demonstrate that her struggle will continue, even though she herself can no longer lead it. But we will carry on, and after me, others will continue to fight against these structures of power.

VALIE EXPORT & KETTY LA ROCCA, 'BODY SIGN' from 16 December 2025 to 28 February 2026 at Thaddaeus Ropac Milan. Curated by Andrea Maurer and Alberto Salvadori in collaboration with Studio VALIE EXPORT and the KETTY LA ROCCA Estate

Hannah Silver is a writer and editor with over 20 years of experience in journalism, spanning national newspapers and independent magazines. Currently Art, Culture, Watches & Jewellery Editor of Wallpaper*, she has overseen offbeat art trends and conducted in-depth profiles for print and digital, as well as writing and commissioning extensively across the worlds of culture and luxury since joining in 2019.