Bespoke Partnership

Change Maker Cassie Quinn on algae, flax and the future of fashion

Cassie Quinn’s regenerative fashion lab in London is exploring biomaterials to help reduce fashion industry waste

In partnership with E.ON

Fabric made of food waste, algae and plants? A smart re-examination of time-honoured flax fibre as a cutting-edge resource for sustainable garment production? These are the ongoing projects at Cassie Quinn’s CQ Studio – a regenerative fashion lab based at Makerversity in Somerset House, London – and have seen Quinn selected to be part of Wallpaper* and E.ON’s Change Maker series, which reveals inspiring stories of those taking action against climate change.

Bioinformed design, Quinn explains, is looking at biology and nature as a source of inspiration for design and material manufacture. With the intensive production processes of the global fashion industry contributing to around ten per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions and consuming more energy than the aviation and shipping industries combined (according to a 2018 United Nations report), the need for low-impact, regenerative alternatives is more relevant than ever.

Tackling fashion industry waste

‘There’s so much waste produced in fashion but nature doesn’t have waste streams,’ says Quinn. ‘Everything in nature is a resource. My thinking is, if we could apply nature’s methodology to fashion, one of the world’s biggest industries, we could really make a significant impact.’

Quinn’s lightbulb moment came during the second year of studies for a fashion textiles degree at the University of East London. ‘I was working on a module called “fast fashion”. We were having to learn how to operate in a system that I felt was really wrong.’ Through research and exploration, she began to ask questions. ‘How can I use my skills and practices in textiles to create a better and more positive impact on the fashion industry and make a difference?’

Regenerative waste, a quest for sustainability and the ongoing disruption caused by the fashion industry (the UK alone throws away more than 300,000 tonnes of textile waste each year, according to waste charity Wrap) became empowering inspirations. ‘That led me down the path of seeing that nature can really be this valuable, key tool to make things more regenerative, more sustainable and less disruptive.’

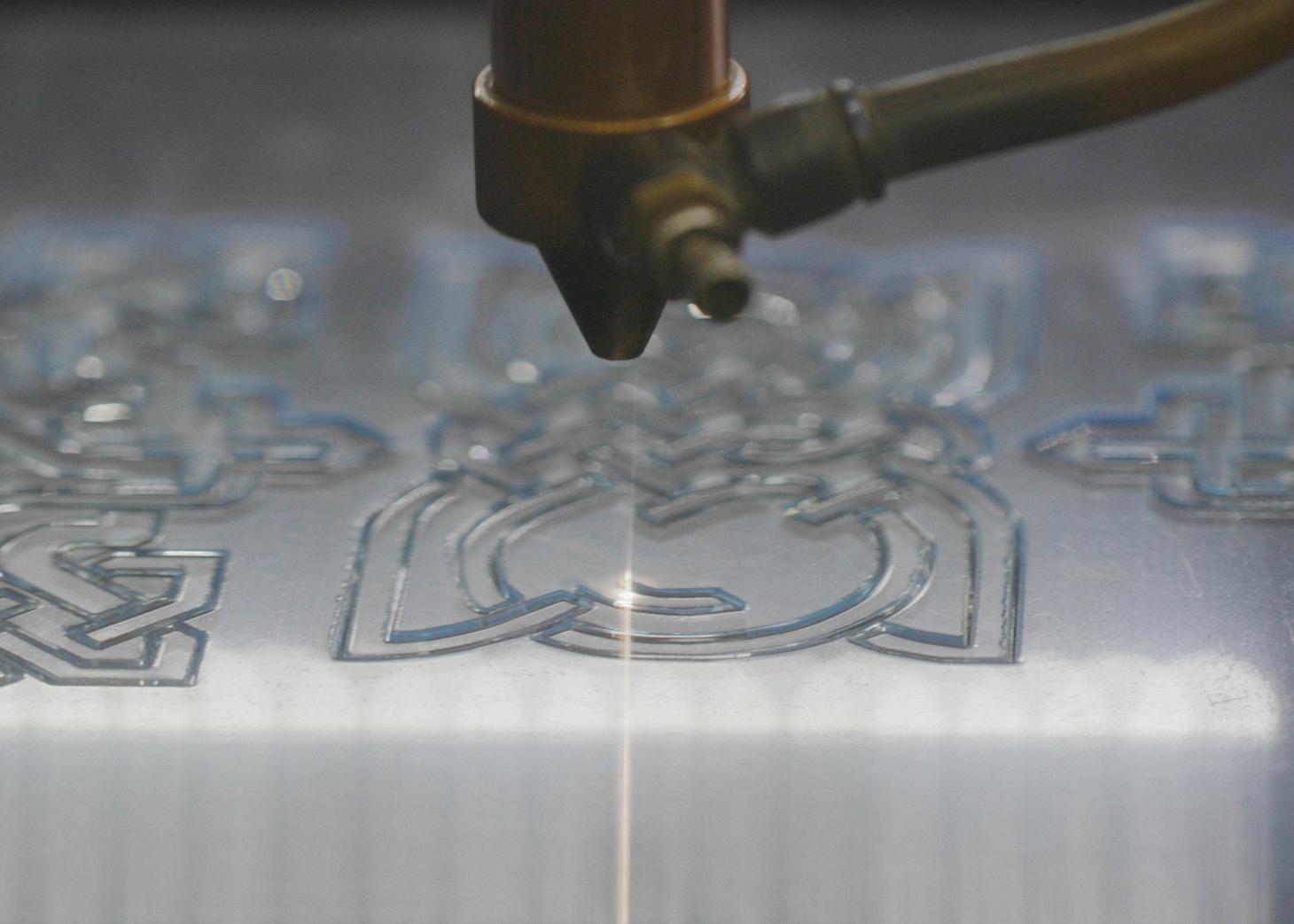

A process of ‘deconstruct, destroy, rebuild’ drove Quinn’s persistently curious, multidisciplinary approach. It’s about ‘looking at material and stripping it right back down to see what it’s made up of. And then asking what new tools you can use to build something completely different and brand new. For me, it’s about real exploration and experimentation and even when things go wrong, you can learn something new.’

Biomaterial breakthroughs

A significant breakthrough was discovering that it was possible to make materials from the fast-reproducing organism that is algae.

Working with an algae polymer with properties similar to that of petroleum-derived, environmentally impactful plastic, Quinn worked on developing a fabric that was non-toxic, water-resistant and biodegradable, incorporating natural dyes before spinning the thread to reduce water usage and production-related toxicity. ‘Whenever I look at a new material, there’s no waste in my eyes, I’m just thinking, what are all the different waste streams that are produced and how can they be re-incorporated back into the process?’

Another unlikely rediscovery and material reconsideration was flax – the plant-stem, bast fibre that has been used to make hypoallergenic, moisture-resistant and breathable linen for over 30,000 years. ‘Flax used to be a massive industry in Ireland [Quinn grew up in Belfast], but it’s only really used to manufacture linen. And linen’s particular qualities – its tendency to wrinkle and slub – restricts its use in the fashion industry.’ Quinn only sees the positive – that linen is biodegradable and breaks down in just a few weeks when buried in soil. At CQ Studio, using a combination of traditional craft techniques and modern, innovative processes, a length of flax can be employed to make eco-friendly faux leather and fur.

‘Biomaterials (like flax fibres) are very important because they’re non-invasive on our planet and the environment,’ says Quinn. ‘I think we sometimes forget that a polyester T-shirt is essentially choking our Earth. And when we work with materials that are biodegradable, it means that we’re not having [such] a negative impact on the planet.’

A call for wider sustainability

The fashion industry, Cassie believes, has an awful lot of catching up to do. ‘The main reason why these groundbreaking biomaterials are not widely adopted by manufacturers comes down to scale of production. We also need to be really pushing designers to demand that they need to use these materials so that the products that consumers buy are natural and sustainably sourced. Send a message out that we don’t want to use anything that’s inauthentic or could potentially harm the planet.’

The next step of Quinn’s biomaterial journey is to get a high-profile creative talent to work with the product ‘to really demonstrate its true potential’.

Her big ambition is for an endless regenerative, material circularity. If clothing materials can be compostable, she says, it means that when the items are no longer worn, ‘you can put them in your food bin and you are actually helping provide an extra function, a direct source for something else. So your T-shirt could be the food source for a sunflower.’

Meet more Change Makers – people who are taking action for climate – at eonenergy.com

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Simon Mills is a journalist, writer, editor, author and brand consultant who has worked with magazines, newspapers and contract publishing for more than 25 years. He is the Bespoke editor at Wallpaper* magazine.

-

Thebe Magugu brings Afro-modernism to Belmond’s Mount Nelson hotel

Thebe Magugu brings Afro-modernism to Belmond’s Mount Nelson hotelA hotel suite and acultural platform on home turf mark the South African fashion designer’s first major move into interior and product design

-

Experience Ken Gun Min’s explosively colourful work at his LA exhibition, opening this weekend

Experience Ken Gun Min’s explosively colourful work at his LA exhibition, opening this weekendThe Korean artist’s third solo exhibition at Nazarian/Curcio runs from 21 February to 28 March 2026, unveiling shockingly vibrant and richly ornamented works

-

Art meets furniture in UniFor’s new Milanese installation

Art meets furniture in UniFor’s new Milanese installationAs part of Milano MuseoCity, UniFor sets Francesco Somaini’s 1970s sculptures in dialogue with Aldo Rossi's furniture designs, exploring their respective urban visions (on view until 15 March 2026)