‘Echo’ lamp is a poetic love song to West African culture

Local craft traditions are at the heart of Brendan Ravenhill Studio and Maison Intègre’s Wallpaper* Handmade X project

The craft traditions of West Africa may be largely uncharted territory for the design industry. But thanks to the French company Maison Intègre, which specialises in curating rare objects from the region and creating unique pieces with craftspeople from Burkina Faso, West Africa’s distinctive union of culture and craft is being brought to the fore, sensitively and authentically.

Founded by Ambre Jarno, a former television executive who lived in Burkina Faso between 2012 and 2014 while helping to develop a network there, Maison Intègre was born of her encounters with local antique dealers, who exposed her not only to African art and design, but its role in cultural traditions and rituals.

Top, a beeswax model of the lamp is wrapped in a mix of clay and horse dung, secured with metal wires, and baked for a few hours. Bottom, once the clay has hardened and the wax melted, metalsmith Alidou Zoungrana drains the melted wax into a bowl, for reuse.

Since 2017, Jarno has cultivated a distinctive collection of furniture, textiles and objects that honours the region’s heritage, while easily fitting into the contemporary home. Including exquisitely carved wooden ladders that are commonly used to enter granaries in the Lobi and Dogon communities of Mali and Burkina Faso; statuesque stools carved from single blocks of wood by the Senufo people, who live in Côte d’Ivoire, Mali and Burkina Faso; and sculptural wooden pulleys used by the nomadic Tuareg people from Niger to draw water from wells, the collection speaks of the fusion of form and function.

‘I really love the simplicity of the design, and the fact that we don’t call that “design” in Africa. It’s instinctive,’ explains Jarno. ‘Just in one country, there can be 15 individual ethnic styles. The diversity is fascinating.’

For this year’s Handmade, we paired Jarno with the Los Angeles-based lighting and furniture designer Brendan Ravenhill, who was born in Côte d’Ivoire and spent part of his childhood in Abidjan. Ravenhill’s roots in the region run deep – his grandparents were missionaries there in 1946, and his parents met there as linguistics students.

Top, metalsmiths Ousmane Koïta and Denis Kabre remove the melting pot to add fuel to the fire while Roger Kabre observes. Bottom, the recycled metal for the lamp is melted at 1,200°C over the outdoor fire.

Ravenhill, who speaks fluent French with an African accent, recalls: ‘I grew up being exposed to African art. We spent every weekend going to the markets looking for African treasures and my father would always educate us on what we were looking at. I grew up with this very African definition of beauty, and to Ambre’s point, what we call design is so intrinsic there and so cultural. It differs from culture to culture, but there’s something universal about it in the same regard.’

For Ravenhill, this context has influenced his approach to designing utilitarian objects, and the effort to impart beauty, language and narrative to pieces. His design for the ‘Echo’ lamp – made using lost-wax casting by a team of master metalsmiths in Ouagadougou, part of Jarno’s network of craftsmen – touches on the duality of love in its pairing of two curved shells that cradle each other.

Top, the molten metal is poured into the hollow clay mould, filling the space left by the beeswax model. Bottom, the metal is left to cool and harden in the clay moulds for about an hour and a half.

With one serving as the light source and the other as the projector, neither piece would be able to function without its mate. Each piece perches on three little legs, and their difference in size suggests a parent-child relationship between the two. The light source is intentionally concealed so that your focus is on the effect of it shining on the interior of the larger object – the recipient of that ‘love’.

‘From our initial conversation about the theme of love, we decided that there would be two pieces to showcase the idea that love can’t exist in isolation. That opened up this language of interaction and allowed us to play around with how a lamp could have this duality,’ says Ravenhill. ‘We also wanted the object to show that it was made from this lost-wax casting process. It’s not trying to be highly polished and machined, but it displays a lot of hand-work and body.’

Top, Denis Kabre breaks open one of the clay moulds, before removing the wires that kept it together. Bottom, the clay layers are cleaned away to reveal the lamp’s metal shells, which will be polished with a metal file for a smooth finish.

Beyond being a metaphor for the dynamics of love, the ‘Echo’ lamp also subtly references the African cultural tradition of dancing while wearing masks – an unintentional gesture on Ravenhill’s part, but one that instantly spoke to Jarno when she saw the first draft of the design. Ravenhill says, ‘I initially didn’t make the connection to masks, but when Ambre mentioned it, it struck a chord, especially in the way some of the volumes are resolved. There’s a lot of beautiful work and sensual detail that happens on the inside of a mask, in the way it is hollowed out to hold the head or the body, and its nice to think that Ambre saw that connection, even though I wasn’t fully conscious of it.’

Jarno and her assistant Giulia Maréchal spent six weeks in Ouagadougou, working with the team of local metalsmiths led by Denis Kabre in his small courtyard workshop, helping them create the prototypes for the lamp. The experience was mutually enriching and Maison Intègre plans to open its own workshop in the area by 2020, providing good tools and safe working conditions and employing local craftspeople.

Despite never meeting in person, Jarno and Ravenhill’s shared understanding of and affection for the techniques and heritage that inform the ‘Echo’ lamp, are ultimately what make it sing. A poetic love song to West African culture if there ever was one.

As originally featured in the August 2019 issue of Wallpaper* (W*245)

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox

The finished ‘Echo’ lamp by Brendan Ravenhill Studio and Maison Intègre.

INFORMATION

Pei-Ru Keh is a former US Editor at Wallpaper*. Born and raised in Singapore, she has been a New Yorker since 2013. Pei-Ru held various titles at Wallpaper* between 2007 and 2023. She reports on design, tech, art, architecture, fashion, beauty and lifestyle happenings in the United States, both in print and digitally. Pei-Ru took a key role in championing diversity and representation within Wallpaper's content pillars, actively seeking out stories that reflect a wide range of perspectives. She lives in Brooklyn with her husband and two children, and is currently learning how to drive.

-

Shigeru Ban’s mini Paper Log House welcomed at The Glass House

Shigeru Ban’s mini Paper Log House welcomed at The Glass House'Shigeru Ban: The Paper Log House' is shown at The Glass House in New Canaan, USA as the house museum of American architect Philip Johnson plays host to the Japanese architect’s model temporary home concept

By Adrian Madlener Published

-

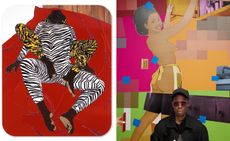

Artist Mickalene Thomas wrestles with notions of Black beauty, female empowerment and love

Artist Mickalene Thomas wrestles with notions of Black beauty, female empowerment and love'Mickalene Thomas: All About Love’, a touring exhibition, considers Black female representation

By Hannah Silver Published

-

New Phaidon book celebrates the world's best designers

New Phaidon book celebrates the world's best designersDesigned for Life: The World’s Best Product Designers by Phaidon celebrates the rich contemporary landscape of product design

By Tianna Williams Published