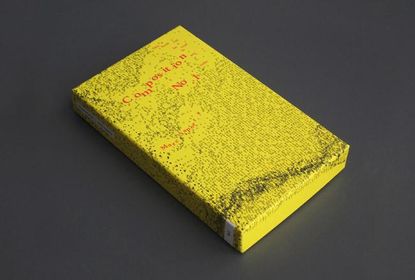

Composition No. 1, published by Visual Editions

In a written world characterised by links, tweets and SMS slang, it’s amazing how naughty it still feels to hold a book in your hands and skip to the last page before you’ve read the first. But that’s exactly what Composition No. 1 invites you to do.

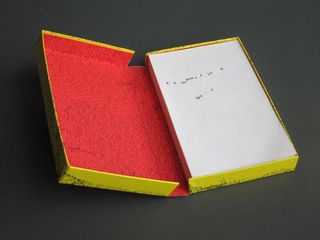

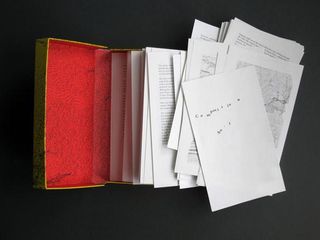

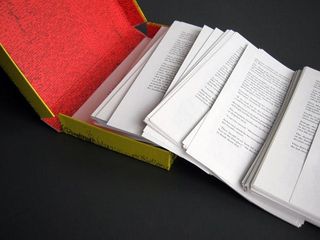

A little known tome by Marc Saporta, published in 1962 - and reinvented today by young publishing house Visual Editions - it is made up of entirely loose pages, each with their own self-sufficient narrative. With no page numbers or chapters, you can shuffle things around as you please. Yet still, the urge not mess up the original order is strangely overwhelming.

Composition No. 1 was the first ’book in a box’ when it was published, and went on to inspire later works like The Unfortunates by BS Johnson. An interconnected web of stories about a group of Parisians during the Second World War German occupation, it both challenges our notions of what a book is and the way we read it.

’It was the first book to demand active participation, or what we might call today, interactive,’ says Tom Uglow of Creative Labs Google and YouTube, in his forward to Composition No. 1 - a concept that makes it particularly apt for today.

To rework it for the 21st century, Visual Editions - the London publishing house whose central tenet is the concept of ’visual writing’ - called in Sheffield-based studio

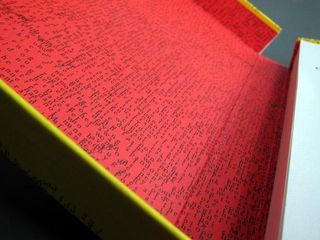

http://universaleverything.com/" target="_blank" >Universal Everything, well known for its interactive screen-based work. As well as redesigning the book, it also created unique, digitally-generated artwork for the backs of each page.

While the process of reading becomes increasingly screen driven, Visual Editions and Universal Everything have been clever to emphasise the tactility of the physical book in this way. However, with the multiple different entry points to its narrative, Composition No. 1 also lends itself brilliantly to the iPad - a point not lost on the publishers. Once again they turned to Universal Everything, who have designed a delightfully simple accompanying app, whose pages keep shuffling until you tap the screen.

See more of the Composition No. 1 iPad app. Watch the video

Once you’ve got over the compulsion to keep the pages in order, it makes for an engaging experience. Sure, it’s not the most cohesive of reads but if you don’t like a fragment of the story you can skip happily onto the next. And the snippets of narrative are oddly compelling as they invite you momentarily into each character’s world. Then - of course - there’s the added bonus that you get to choose how the book ends.

Visual Editions called in Sheffield-based design studio Universal Everything to rethink the book for the 21st century

Composition No. 1 is made up of entirely loose pages, each with their own self-sufficient narrative

With no page numbers or chapters, its order can be shuffled as the reader pleases

An interconnected web of stories about a group of Parisians during the Second World War German occupation, it both challenges our notions of what a book is and the way we read it

While the process of reading today becomes increasingly screen driven, Visual Editions and Universal Everything have been clever to emphasise the tactility of the physical book with their design

The back of each page features a unique, digitally-generated artwork

Composition No. 1 is available for £25 from the Visual Editions website

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox

Malaika Byng is an editor, writer and consultant covering everything from architecture, design and ecology to art and craft. She was online editor for Wallpaper* magazine for three years and more recently editor of Crafts magazine, until she decided to go freelance in 2022. Based in London, she now writes for the Financial Times, Metropolis, Kinfolk and The Plant, among others.

-

The visual feast of the Sony World Photography Awards 2024 is revealed

The visual feast of the Sony World Photography Awards 2024 is revealedThe Sony World Photography Awards 2024 winners have been revealed – we celebrate the Architecture & Design category’s visual artists

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

Don’t Move, Improve 2024: London’s bold, bright and boutique home renovations

Don’t Move, Improve 2024: London’s bold, bright and boutique home renovationsDon’t Move, Improve 2024 reveals its shortlist, with 16 home designs competing for the top spot, to be announced in May

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

Perfumer H has bottled the scent of dandelions blowing in the wind

Perfumer H has bottled the scent of dandelions blowing in the windPerfumer H has debuted a new fragrance for spring, called Dandelion. Lyn Harris tells Wallpaper* about the process of its creation

By Hannah Tindle Published