Beirut’s new movers and shakers

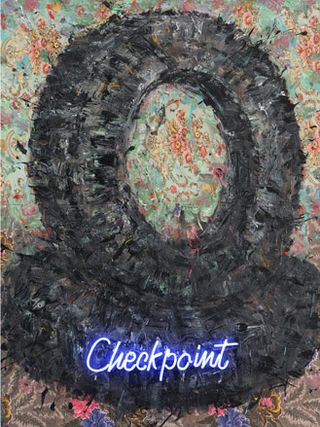

Ayman Baalbaki, painter

Ayman Baalbaki has the sharpest brush in Beirut. For the last decade, he has been flaying his country of its flesh through paintings and installations that explore the political turmoil in the Middle East. He references heavily his primary audience - his fellow citizens - as well as representing Beirut's seemingly never-ending process of construction, destruction and reconstruction.

If it sounds gloomy, it isn't. What sets Baalbaki apart is that he eschews rage. There's a warmth - even a humour - to his work which is less about making light of dark situations, and more about accepting that he lives in a region where life and death is all-too-often decided from 38,000-feet. Driven out of his village of Odeisse in 1976, Baalbaki was a refugee before his first birthday and went on to experience at first-hand life on the front-line'.

'I belong to a generation of Lebanese artists who don't have anything to say except about the war,' he says. 'We have been left with the contradictions of war but its reminders are being erased. I feel that the opposite is necessary, that we need to preserve reminders of it as well.'

Beirut is a city with an identity crisis. Is it Arab, Mediterranean or European? Muslim or Christian? Is it the bastion of Resistance or the stronghold of tolerance? Is it the capital of a country that only became independent in 1943 or one of the oldest continually-inhabited cities on earth that was already ancient when Athens was born?

These are questions that Beirutis have yet to answer. Hopefully, they never will. Millennia of navigating their city's multiple identities has bestowed upon them a natural cosmopolitanism that other more vocal aspirants to the mantle can never truly emulate. Beirut is cosmopolitan because it lives in a state of constant flux. As its inhabitants come and go, they bring new ideas, and because it is not in thrall to a single ideology or dominated by any single community, Beirut not only permits experimentation, it revels in it. Here we profile its new generation of movers and shakers and take a look at their work.

'The Parliament' by Ayman Baalbaki, 2002

'Ciel charg des fleurs' by Ayman Baalbaki, 2004

'Checkpoint' by Ayman Baalbaki, 2009

'Destination X' installation by Ayman Baalbaki, 2010

Joe Barza, chef

When Joe Barza enrolled in Beirut's hotelier school, he quickly learned two lessons. First, there are invariably as many opinions about the way tabbouleh ought taste as there are people at the table. Second, Lebanese diners seemed loathe to credit a compatriot chef, but bring in a French or an Italian chef and the same people would turn cartwheels in admiration. 'I used to work 18-hour days, sometimes seven-days a week,' says Barza. 'I once sat on a can of powdered milk, shelling 30 kilos of shrimps and all I could think was why the diners treated the chefs like servants instead of artists.' And so it was that in 1988, Barza decamped to Cape Town, where he began his 'real training'.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox

In 1994, he returned a fully-fledged head chef, to find Beirut little changed. 'I realised Lebanese diners were used to complimenting foreign chefs because they thought the food more complicated. But just because our food is simple, doesn't mean it's easy.'

Now executive chef of the Chase restaurant chain, Barza's latest quest is to expand the average person's culinary knowledge of what Lebanon has to offer. He regularly travels the country in search of new ingredients and recipes. 'We have such excellent produce - fresh herbs, vegetables, pickles, preserves and dairy products - that people don't know about.'

Kichk and potato crossini by Joe Barza

Serves 80 to 100

Ingredients

5kg flowery potato, baked but still hard

500g kichk

0.5L extra virgin olive oil

1kg tomatoes, seeded and diced

1 bunch coriander, chopped

50g garlic, peeled and chopped

200g onion, chopped

200g shredded mozzarella

200g shredded halloumi

40g lemon juice

Method

Cut the potato into thick circles, and grill them on a flat top

Heat the olive oil in a pan and fry the onion

Add the garlic, the coriander, the tomato and the kichk to the onion and cook for five minutes

Add the cheeses

Adjust lemon juice and salt and pepper

Leave to cool

To serve

With a spatula, paste the topping on the potato and gratinate

Stuffed chicken with burghal and tomato source by Joe Barza

Serves 80 to 100

Ingredients

10 pieces/1kg boneless Whole Chicken, Flattened

50g garlic, smashed

400g olive oil

1 bunch mint, chopped

200g chick peas, half-boiled

500g burghul

3 bunches parsley, chopped

200g lemon juice

100g melace of pomegranate

3L finished plain tomato sauce

75g onion, chopped

10g salt

500g tomato, chopped

5g sweet pepper

15 big leaves

Swiss Chard, steamed

Method

For the stuffing:

Mix 300g olive oil, burghul, chopped tomato, parsley, chick peas, onion, mint, lemon juice, salt and pepper in a bowl

For the chicken:

Put the chicken on cling film, and rub with garlic, olive oil, salt, and pepper

Put the Swiss chard in the middle of the chicken

Put the stuffing on top of the Swiss chard

Roll the Swiss chard around the stuffing, and then roll the chicken as galantine

Tighten the galantine with the cling film and steam the whole until the chicken is cooked

When cooked, remove the cling film, and colour the chicken on a flat top

For the sauce:

Finish with plain tomato sauce

To serve

Place the chicken on a plate, and drizzle tomato sauce on top

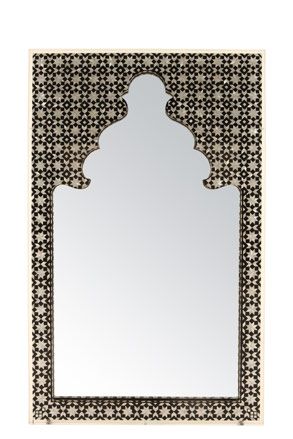

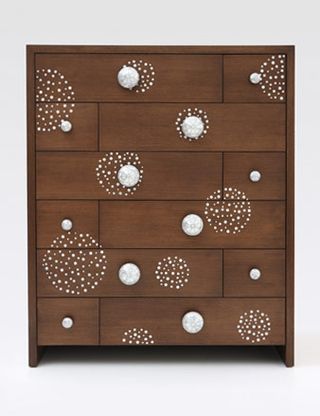

Nada Debs - furniture designerNada Debs was brought up in Kobe, studied at Rhode Island School of Design and worked in London before moving 'back' to Beirut, a city she barely knew, in 1999. By rights then, she deserves to be confused. Instead, as heir to two disparate cultures, Debs has chosen a design path that marries the geometric but decorative Middle Eastern tradition with the pure forms of Japan. This quest is evident in the two eponymous design stores she runs in central Beirut's Saifi Village; the newer is devoted to Debs' larger items that make up her East Is East collection, as well as her most recent armchair, Arabesque Moderne, which lies somewhere between art and functionality.

'Of course, furniture has to look good, but it has to feel good too and not only to sit with emotionally, but also to sit on physically,' Debs says. 'This trend of furniture as art, I like the idea but for me, it's more important that furniture is functional.' And, she reflects: 'If you go to Japan, you see this geometric work. It looks almost Middle Eastern, it's funny how there are similarities. Sometimes, I don't know where I am. I'm lost in translation. Okay, maybe not lost, more like in the process of evolution.'

'Clear C Table', 2005

’Arabian Nights Mirror’, 2005

’Pebble table’, 2005

’Box low table’, 2008

’Ali Baba cabinet’, 2005

’Arabesque armchair’, 2007

’Arabesque armchair’, 2007

’Pebble table’, 2005

’Fireworks chest of drawers’, 2005

’Coffee bean table’, 2003

Rabih Kayrouz - fashion designer

As years go, 2009 was rather excellent for Rabih Kayrouz. In July, he opened his Paris boutique in the premises of the old Theatre de Bayblone on Boulevard Raspail, where Beckett first made the world wait for Godot in 1953; a few days later, his show was part of the official calendar of events at the Paris fashion week.

Having left Beirut in 1991, he studied fashion design at the Ecole de la Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture and afterwards, apprenticed at Dior and Chanel. Still, Kayrouz never forgot home; he returned in 1995 to do his military service - fresh from a competition for young fashion designers at the Carrousel du Louvre.

The detour was to do no lasting damage; days after being demobbed, Kayrouz was asked by a friend to design her wedding gown, which proved to be an excellent calling card; the orders rolled in. Today, Kayrouz does both couture and a prêt-a-porter, both defined by their unmistakably Levantine sensuality; like Beirut itself, his clothes are an amalgam of the chaotic and the ordered, the restrained and the exuberant, the classical and the contemporary, located in time somewhere between the Roman Republic and the 22nd-century.

From Kayrouz’s 2010 ’Salwa’ collection

From Kayrouz’s 2010 ’Salwa’ collection

From Kayrouz’s 2010 ’Salwa’ collection

From Kayrouz’s 2010 ’Freeze’ collection

From Kayrouz’s 2010 ’Freeze’ collection

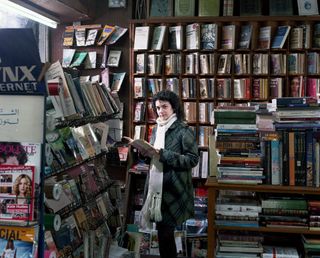

Sandra Dagher and Lamia Joreige - arts activists

When gallery owner Sandra Dagher and contemporary artist Lamia Joreige sat down for a chat one day in 2004, one topic dominated discussion: Beirut had galleries galore, but with no national art museum, there was no non-profit space where the country’s artists could exhibit. Something had to be done.

Five years on, The Beirut Art Centre opened its doors, occupying the premises of a derelict factory in a partially abandoned industrial district near the Beirut River. ’We needed a space like this for Lebanese artists,’ says Dagher. ’It’s not enough for Lebanese artists to exhibit internationally. Not everyone can travel to New York or Paris to see a show. Now we have a chance to make art that was inaccessible, accessible,’ adds Joreige.

The Centre houses a small auditorium, a library, and fledgling electronic reference system which will eventually list bios of every Middle Eastern artist, alive or dead, including photographs of work, links to articles and video footage. It’s a space, says Joreige that ’aims to create a platform for debate by showcasing a diverse range of art, of all modes of expression.’ The goal is to create an institution that will survive, regardless of who’s in charge. And in a country where institutions often live or die according to the whims of one ego, that might be the greatest revolution of all.

The Beirut Art Centre’s auditorium

An exterior view of the Centre

’Prisoner of War’ installation at the Beirut Art Centre

Gallery space at the Centre

The bookshop

The terrace

Youssef Tohme - architect

Youssef Tohme is easily the most exciting architect working in Lebanon, yet his unassuming approach means he flies under most radars. His anonymity won’t last; with a slew of projects coming to completion, he’s already finding himself in the spotlight.

Tohme’s buildings blur the line between structure and sculpture, indoors and outdoors. Oriented towards a horizon: the sea, the sky, the mountains, they leave a light footprint and are based on geometries that give the simultaneous impression of hoary monolith and future wonder.

’Architecturally, Lebanon is not a dialogue, it’s a collection of objects that ignore one another and their surroundings,’ he says. ’But it doesn’t have to be like this. When it’s done properly, human intervention adds to the landscape and makes it even better.’

Tohme is pre-occupied with the spaces created by buildings. Take his Jesuit University extension, a single sculpted mass, which appears to have been designed around its voids, or a private villa in the Broumana mountain resort which covered a number of different functions; Tohme resolved the problem by breaking the project into cantilevered units, scattered across the plot like a series of sculptures, emerging from the surrounding woods.

The Universite St Joseph extension by Youssef Tohme in partnership with 109 Architectes, under construction, 2005 - 2011

The Universite St Joseph extension at night

A contrasting view of the Universite St Joseph by Youssef Tohme in partnership with 109 Architectes

A villa in progress in Kornet Chehouane, Lebanon, by Youssef Tohme, 2008 - 2011

The Kornet Chehouane villa by Youssef Tohme

The Kornet Chehouane villa by Youssef Tohme

The interior of a villa under construction in Kaakour, Lebanon, by Youssef Tohme, to be completed in 2010

Sahar Mandour - journalist and writer

’Sometimes I can’t believe how much I hate it and sometimes I can’t believe how lucky I am to live here,’ says Sahar Mandour. ’(Beirut is) intelligent and stupid, beautiful and ugly, free and repressed, generous and unjust, it feels like an example of the universe one second, a sewer the next.’

Mandour is best known for both her work as editor of Shabab, the youth pages of Al Safir, Lebanon’s left-wing newspaper, and her writing - especially her last novel, Hob Beiruti (Love, Beirut Style). Her first, I Will Draw a Star on the Forehead of Vienna, tells the story of beautiful but naïve woman who has sex at an early age, undergoes a hymenoplasty, cheats on her husband but doesn’t feel bad about it and subsequently divorces him. In the Middle East - even in its most open society, where the cultural war is so intense that people who write about taboo subjects can find themselves hauled before a judge, or worse - the almost disinterested way Mandour presents her heroine is notable. Love, Beirut Style continues in this lack of moral judgement. It’s a book that could only be written in the Middle East’s most permissive city.

’I do push buttons, but I do it without being offensive,’ Mandour explains. ’I’m not trying to be controversial. Here things start as a scandal and end in nonchalance, so I prefer to be subtle. I throw in these fiery ideas but I always present them as though they were as simple as a drink of water.’

Middle East Editor

-

Minotti presents Giampiero Tagliaferri’s Supermoon sofa at Salone Del Mobile 2024

Minotti presents Giampiero Tagliaferri’s Supermoon sofa at Salone Del Mobile 2024Minotti brings its new Supermoon collection to Salone del Mobile 2024, with a unique blend of Milanese and Californian aesthetics

By Jasper Spires Published

-

Step inside Juno Omakase, London’s smallest counter dining experience

Step inside Juno Omakase, London’s smallest counter dining experienceJuno Omakase, inside Los Mochis Notting Hill, offers a one-of-a-kind tasting menu in which Tokyo meets Tulum

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

‘Help me go faster’: How Nike Air is priming its athletes for Olympic success

‘Help me go faster’: How Nike Air is priming its athletes for Olympic successAhead of the Paris 2024 Olympics, Nike’s chief design officer Mike Lotti opens up to Wallpaper* about its latest high-performance sneakers, developed alongside world-leading athletes and honed using AI technology

By Ann Binlot Published