The frame game: an Italian startup is focused on transforming the fashion eyewear business

Roberto Vedovotto likes to think of Kering Eyewear as a startup, a lean, mean entrepreneurial upstart bringing innovation and disruption to a business dominated by a few too-powerful players. But if this is a startup, it’s an unusually smart one. No Ikea trestle-tables and sticker-plastered laptops here, none of the scruffy urgency of Silicon Valley or Shoreditch.

Vedovotto’s startup is backed – to what percentage has not been disclosed – by luxury goods giant Kering Group (formerly known as Gucci Group) with a 20-strong brand stable that includes Gucci, Saint Laurent, Bottega Veneta, Alexander McQueen and Stella McCartney. And its new inside-but-outside eyewear division has suitably glamorous quarters in Villa Zaguri, a smartly restored Renaissance pile just outside Padua.

Less than half an hour’s drive west of Venice, this is the heartland of Italy’s high-end, high-skill manufacturing base. And the local skill set includes eyewear. Safilo, the world’s second largest eyewear company after Luxottica – and the company that, until recently, made eyewear under licence for a number of Kering brands – is based here.

Vedovotto, a former Safilo CEO, formed Kering Eyewear in September 2014 with the clear intention of challenging the established order and pushing a new business model for the industry. A report by Exane BNP Paribas called the launch an ‘eyewear revolution’.

The luxury goods industry has long licensed out its fragrance, eyewear and beauty businesses, even though these are the real money-spinners. They are also ‘entry products’, the point where younger customers especially get their first ‘experience’ of a brand and hopefully develop a taste for more.

This arrangement can seem counter-intuitive, particularly when it comes to eyewear. The premium fashion segment of the eyewear market could now be worth as much as $12.5bn. It is also an area with massive growth potential. Licensing arrangements then mean not only a loss of creative control, but also a loss of pure profit. The brands pull in huge royalty payments, but they are only a percentage of the possible returns. At the time of the launch of Kering Eyewear, Vedovotto said the Kering Group’s eyewear business was worth €350m, generating royalties of €50m.

However, while the luxury goods giants have been buying back licences in other categories, most have considered producing and distributing eyewear too far out of their comfort zone. ‘Eyewear is a very technical product,’ says Vedovotto. ‘It also has a completely distinct distribution model.’ Supplying thousands of independent opticians around the world is definitely not part of the luxury goods group's skill set. Still, with a number of Kering licences coming up for renewal, Vedovotto and Kering Group CEO François-Henri Pinault thought it was time to take a risk. The rewards were simply too great to ignore.

Kering Eyewear is based around what Vedovotto calls a mixed-model. Essentially, it has taken back control of design and product development, working with the creative teams of each brand, marketing and brand management, logistics and distribution. The only link of the ‘value chain’ that it hasn’t ‘internalised’ is manufacturing. But instead of being locked into deals with the licensed manufacturers, it is now free to deal with a whole range of specialist makers. This new model means that Kering Eyewear can ‘create products that are fully aligned with the brands’ DNA’, as Vedovotto puts it. It will also look at upping quality without ramping up prices and undermining the ranges’ entry product promise.

The man charged with making all this happen is Kering Eyewear’s creative director Massimo Zuccarelli, also formerly of Safilo. He heads up a 25-strong team in Padua, which managed to put out nine eyewear collections less than a year after Kering Eyewear was launched (and while their renaissance villa was still being decorated and without Wi-Fi. ‘It was kind of a nightmare, but the energy was incredible,’ says Zuccarelli).

These launch ranges included a debut eyewear collection for the Milan-based jewellery brand Pomellato. Since then, collections by Tomas Maier and Christopher Kane have also been added. The creative relationship with the brands varies, says Zuccarelli: ‘Some teams come up with a very full briefing with shapes, designs, technical drawings and materials. Others present more of a vision. We don’t have a rule. We have the right support for anyone.’ Kane seems to support that. ‘I showed them my crappy sketches and they made them a reality,’ he says, only half-joking.

What seems to most excite Zuccarelli, though, is the range of manufacturers – and thus finishes, materials and effects – he can now show the brands. He seems particularly excited about the Japanese makers that Kering is now working with, even if costs mean he has to use them sparingly. ‘There are a lot of niche eyewear brands in Japan and we are the first people to use those makers for other brands. The finishing of the Japanese makers is different because they are so obsessed with vintage; the galvanic treatment, the polishing, the raw materials they use, the acetates, it really recalls vintage eyewear.’

The group now works with over 30 different suppliers. But, as Vedovotto says, this is not just fancy and indulgence on their part. This wealth of materials and finishes means they can produce ranges with distinct looks and identities. With 11 brands already up and running, Gucci on the way and long term plans to launch more, cannibalisation of sales is an obvious risk. ‘I don’t want to do the same thing as everyone else,’ says Kane. ‘They are constantly bringing these new techniques and technologies to the table so everyone has options and can do something different.’

Inevitably, perhaps, it is with the debut eyewear ranges that Zuccarelli has had the most freedom and pure fun. For Tomas Maier, he has developed a small range of contemporary aviators with flat lenses and other reworkings of American classics.

With Pomellato, the job was to create a range that somehow built on the brand identity without doing the obvious. ‘We wanted to do something different from just putting jewels or stones on the glasses,’ says Zuccarelli. ‘The idea was to replicate the feeling and the craftsmanship. And it wasn’t easy. We worked on the acetates to replicate the colour of the stones and the polishing and the finishing to replicate the feeling of the stones. The result is incredible.’ Sometimes these vivid acetates in different colours are melded in one frame, to startling effect. As Pomellato creative director Vincenzo Castaldo says, the Kering Eyewear team has also managed to do something smart and playful with a key part of the Pomellato design language. ‘Traditionally, a griffe was just a functional element to keep a stone in place,’ says Castaldo. ‘But in the early 1990s, Pomellato transformed it into something decorative in its own right, part of the overall aesthetics.’ The griffe reappears on the eyewear collection, transformed into a hinge.

With other brands there were different challenges. For Stella McCartney, the team worked with acetate specialists Mazzuchelli to develop a sustainable bio-acetate. And Zuccarelli is determined to use sustainable materials across all ranges within a few years. Material development is key, he says, and he is keen on using new and unique materials, when economies of scale allow. Zuccarelli is more than conscious that the venture will fail if he can’t bring all this novelty and innovation in under a certain price, or produce ranges with a ‘price architecture' that fits the brand and the market.

‘The prototypes we show the brands are exactly as they will be in the final production,’ he says. ‘Every problem, every detail has been worked out. We understand how it can be industrialised and how much it will cost. And for every prototype, there are alternatives, fully costed in the same way. It is very difficult because there is this balance between creativity and industrial design. And we are in the middle. We want to create proper collections based on market needs.’

There are still those, though, who think that however in tune they are with market needs, Kering Eyewear will struggle, at least at first. Startup costs have been significant. A renaissance villa full of the right kind of talent doesn’t come cheap. And when Kering Eyewear was launched, its prize licence, Gucci, still had four years to run. It had to pay Safilo €90m to terminate the licence two years early (Safilo will continue to produce the collection, at least for the next four years). Gucci will become Kering Eyewear property at the end of 2016, and the success of the first Gucci collection is essential.

What Luxottica and Safilo offered, apart from manufacturing know-how, is a huge distribution network and sales force. An Exane BNP Paribas’ report on the launch of Kering Eyewear identified getting to grips with distribution as probably its biggest challenge. And two years on, Luca Solca, head of luxury goods at Exane BNP Paribas, remains unconvinced that the new operation will deliver better returns than the previous licensing deals. ‘Kering Eyewear is an interesting experiment, but it looks like an over-ambitious business proposition to me.’

Vedovotto thinks he can prove them wrong. Distribution will be handled by a dedicated sales team, rather than agents on commission, which is how the licence holders handle it. And though the opticians, department stores and airport outlets won’t be neglected, there will be more accent on Kering’s directly-operated boutiques.

The Kering model is not something Safilo and Luxottica will want to see prosper, especially Safilo, which is far more reliant on its licence deals, but Vedovotto insists that the market is big enough to allow for happy commercial co-habitation. Nor does he see other groups and brands rushing to follow the Kering Eyewear example. ‘The business model we have decided to go for is not for everyone. There are only a few groups that can potentially afford an initiative like this.’

Kering Eyewear is not the only revolutionary in the market though. Warby Parker, for example, has developed from a cult online brand to a serious player that’s now opening its own stores. Vedovotto feels he shares a kinship with Warby Parker in terms of a startup’s flexibility and derring-do. And, ultimately, he believes this is what will get them through. ‘All the people here have the entrepreneurial spirit that is key to this initiative,’ he says. ‘This is the most difficult thing that any of us has done in our lives. But that’s the interesting part. It’s a challenge and a huge opportunity.’

As originally featured in the September 2016 issue of Wallpaper* (W*210)

Roberto Vedovotto, CEO of Kering Eyewear

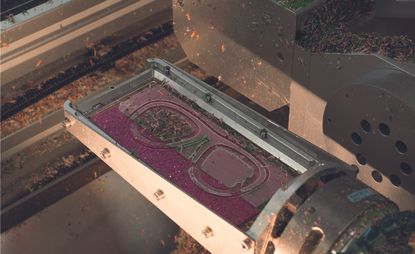

Left: prototype Brioni aviators in development. Right: Massimo Zuccarelli of Kering Eyewear and Vincenzo Castaldo of Pomellato

Villa Zaguri, Kering HQ

Left: Christopher Kane in his East London studio. Right: frames from his first unisex eyewear line launched in partnership with Kering Eyewear

Bottega Veneta for Kering Eyewear

Christopher Kane for Kering Eyewear

Saint Laurent for Kering Eyewear

INFORMATION

For more information, visit the Kering Eyewear website

Photography: Albrecht Fuchs

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox

-

The moments fashion met art at the 60th Venice Biennale

The moments fashion met art at the 60th Venice BiennaleThe best fashion moments at the 2024 Venice Biennale, with happenings from Dior, Golden Goose, Balenciaga, Burberry and more

By Jack Moss Published

-

Crispin at Studio Voltaire, in Clapham, is a feast for all the senses

Crispin at Studio Voltaire, in Clapham, is a feast for all the sensesNew restaurant Crispin at Studio Voltaire is the latest opening from the brains behind Bistro Freddie and Bar Crispin, with interiors by Jermaine Gallagher

By Billie Brand Published

-

Vivienne Westwood’s personal wardrobe goes up for sale in landmark Christie’s auction

Vivienne Westwood’s personal wardrobe goes up for sale in landmark Christie’s auctionThe proceeds of ’Vivienne Westwood: The Personal Collection’, running this June, will go to the charitable causes she championed during her lifetime

By Jack Moss Published

-

The best fashion moments at Milan Design Week 2024

The best fashion moments at Milan Design Week 2024Scarlett Conlon discovers the moments fashion met design at Salone del Mobile and Milan Design Week 2024, as Loewe, Hermès, Bottega Veneta, Prada and more staged intriguing presentations and launches across the city

By Scarlett Conlon Published

-

Brunello Cucinelli takes a Roman holiday to launch new eyewear collection

Brunello Cucinelli takes a Roman holiday to launch new eyewear collectionWallpaper* joined Brunello Cucinelli’s opulent festivities at Rome’s Villa Aurelia, which heralded a new eyewear collection created in collaboration with EssilorLuxottica

By Jack Moss Published

-

Extraordinary runway sets from the A/W 2024 shows

Extraordinary runway sets from the A/W 2024 shows12 scene-stealing runway sets and show spaces from A/W 2024 fashion month, featuring Murano-glass cacti, rubber armchairs, flashing orbs and more

By Jack Moss Published

-

Saint Laurent closes fashion month with a secret menswear show

Saint Laurent closes fashion month with a secret menswear showAnthony Vaccarello held his latest Saint Laurent menswear show at Paris’ Bourse de Commerce – Pinault Collection on Tuesday evening, rounding out fashion month with a collection infused with a louche, 1980s sensuality

By Jack Moss Published

-

Saint Laurent’s Champs-Élysées store showcases Anthony Vaccarello’s monumental vision

Saint Laurent’s Champs-Élysées store showcases Anthony Vaccarello’s monumental visionA vast new Saint Laurent store on Paris’ Champs-Élysées reflects creative director Anthony Vaccarello’s rigorous, monumental approach to design

By Jack Moss Published

-

This season’s womenswear channels freedom and escape

This season’s womenswear channels freedom and escapeThese S/S 2024 womenswear looks promise an escape from the everyday, and are photographed amid the otherwordly landscapes of the Canary Islands for the March 2024 Style Issue of Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss Published

-

In fashion: the best of S/S 2024 in 12 transporting looks and accessories

In fashion: the best of S/S 2024 in 12 transporting looks and accessoriesThe looks and objects that encapsulate S/S 2024’s mood of escape and discovery, from crystal-studded sunglasses to behemothic beach bags

By Jack Moss Published

-

Introducing Wallpaper* March 2024: The Style Issue

Introducing Wallpaper* March 2024: The Style IssueWallpaper* March 2024 is on sale now, featuring the looks of the season, Demna on modernity at Balenciaga, Rem Koolhaas on 25 years of Prada sets, and Saint Laurent’s new Paris store

By Sarah Douglas Published