On the road: a new monograph of Mario Bellini's vision of 1972 America

Images of America by Mario Bellini, Francesco Binfaré, and Davide Mosconi, provide an autobiographical journey into the recent past.

The road trip is a condensed form of autobiography; we live life through the eyes of the travellers, alighting on their obsessions, fascinations and the truths they are trying to uncover. These images of America are more than just a then-and-now trip into the recent past. In 1972, Mario Bellini was taking part in MoMA’s ‘Italy, the New Domestic Landscape’ exhibition, curated by Emilio Ambasz and struck through with a spirit of post-pop, new tech, neo-utopian design that still resonates today. Alongside Bellini were Joe Colombo, Gae Aulenti, Ettore Sottsass, Gaetano Pesce and Superstudio, among others, and objects were exhibited together with 11 immersive installations that referenced a growing dissatisfaction with materialism and an often-contradictory fascination with technology and alternative lifestyles.

Artist Davide Mosconi, one of Bellini’s travelling companions, with his Arriflex camera on Interstate 80, on the way from Chicago to the Pacific

Bellini’s Kar-a-sutra, which is more ’mobile human space’ than car

Bellini’s contribution was the Kar-a-sutra, a radical apple-green concept car that blended furniture design with multifunctional space. A deliberate riposte to Detroit’s epic inability to accommodate either functional ergonomics or elegant proportions, the Kar-a-sutra was described by Bellini as ‘not just a car but a mobile space, to be lived in’. A project initiated in 1970 in collaboration with Cassina, it was built on one of Citroën’s fabled hydropneumatic chassis, with memory-foam movable seats and an adjustable glazed roofline.

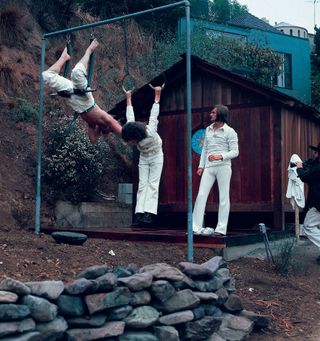

Members of Father Yod’s Source Family, a hippy commune on Sunset Boulevard, Los Angeles

The Kar-a-sutra combined hedonism and practicality, yet in 1972 it was, as Bellini relates sadly, ‘not properly understood’. Forty years later, the concept is seen as a precursor to the modern multi-purpose vehicles, an influential staging post on the way to future cars that could still draw inspiration from architectural space, not the demands of speed.

The MoMA experience instilled within the architect the desire for wanderlust. Together with Francesco Binfaré, who was to become art director of Cassina shortly after, and the artist Davide Mosconi and his assistant, Bellini left New York and headed west. ‘America is the flip side of Europe, a concentration of experiences each contradicting one another. Art, technology, science and social experimentation were all parts of a huge laboratory of the new which I thought I could examine by entering people’s homes,’ he writes in the newly published monograph that reproduces his images of the trip.

A view of Manhattan from Long Island

These weren’t just any old homes. America still held enormous resonance in Europe. ‘There was a time when we (especially the Italians) were obsessed by “lifestyles”,’ he continues, ‘and we started to reflect on the meaning of the things – chairs, sofas, beds, cookers, fridges, televisions – which occupy our living spaces along with us.’

The 1972 journey is a journey among things as well as people. As the writer and editor of La Stampa, Mario Calabresi, notes in his foreword, these images depict an America that is ‘apparently no longer with us’. They are certainly struck through with the rich patina of Kodachrome and nostalgia, of cinematic visions and memories. It was a fertile era for a traveller with an eye for the epic and the absurd, the innovative and the eccentric. America’s place as a font of myth and legend provoked fear, fascination and yearning in Europe, then as now, and the scale of the landscape and the ambition of those that remade it could inspire both awe and bewilderment.

A Chicago crossroads with Bertrand Goldberg’s 1964 Marina City Towers in the background

Bellini and his bearded, camera-wielding travelling companions wanted to take it all in. They were, after all, in the country as guests of MoMA, one of the world’s preeminent institutions for disseminating the message of ‘good design’. The group carried a letter from MoMA, describing them as a ‘team of researchers’. ‘It turned out to be a lifesaver on more than one occasion,’ Bellini writes, recalling a journey that was largely improvised, ‘like a jazz concert’. It read: ‘The bearer of this letter, architect Mario Bellini, an Italian designer of international reputation is interested in visiting factories and homes for a film that he is preparing.’

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox

Travelling from motel to hotel, the Italians occasionally pretended to be reporters from Italian television. Recording the inhabitants was an almost clinically anthropological affair, documenting the interiors and objects that made up the American way of life. Bellini describes the reassuring standards of consumerism as being a way of making up for ‘the sense of disorientation arising from the transient nature of American life’. Interspersed with this snatched study of the culture of plenty were pilgrimages to what might be termed cultural frontiers.

Bellini retraced his footsteps this year while on a lecture tour across the US. In Los Angeles, he captured urban scenes on Santa Monica Boulevard

The architect’s notes from the time are direct and to the point. Warhol’s studio ‘looks like the headquarters of a multinational rather than the “Factory” of an avant-garde artist’, while Paolo Soleri’s Arcosanti was full of ‘students like faithful construction slaves’. After a lot of ‘phone hustling’, the group also made their way into Hugh Hefner’s fabled mansion. ‘No bunnies,’ he noted, ‘but a mise-en-scène not for the eyes of minors: a circular waterbed, an overdose of fluffy carpet and velvet trim, a film projector, early holograms, and a swimming pool for two.’

The temples of Salt Lake City, the Chicago suburb lorded over by Frank Lloyd Wright, the endless desert highway, all led inexorably to the West Coast, home of ‘nomadism’, communes and (truth) seekers: ‘Instead of movie stars there are hippies, gurus and pre-vegans.’ Does this America even still exist? Bellini is now 80 and as busy as ever (he designed the major 2015 Giotto exhibition at Palazzo Reale, Milan).

Today’s Santa Monica is a place of tourism and spectacle, far removed from the 1970s utopia of self-discovery and alternative futures

To celebrate the new book – and to satisfy his perpetual inquisitiveness – the architect recently undertook another trans-American lecture trip with Cassina, taking in New York, Miami, Dallas, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Vancouver and Chicago in just two weeks. Part of the journey was devoted to retracing his earlier steps. ‘We took a taxi to the exact same address on Sunset Boulevard where we found the communes in abandoned villas in the 1970s,’ says Bellini.

On retracing his steps, the 80 year-old Bellini found that a taco bar had replaced the Source Commune’s organic vegetarian restaurant

What the architect found didn’t exactly baffle him, but was clearly disaffecting. ‘It had nothing to do with what we found in 1972, but it’s not easy to explain why it’s different.’ Some things – the giant billboards for example – hadn’t changed but the eclectic chaos of modern Sunset was perhaps a bit too contrived. ‘It’s a place of characters and spectators, a human landscape,’ he says. ‘The people are waiting for you to look at them. I had to understand who was looking at me and what they wanted. It was slightly artificial.’

The Playboy Mansion in Chicago – ‘an overdose of fluffy carpet and velvet trim’

Modern America no longer occupies such a prominent spot in the creative psyche, certainly from a European perspective. Today’s Santa Monica is a place of tourism and spectacle, far removed from the 1970s utopia of self-discovery and alternative futures. And yet the original images still resonate, with their ‘colours unfound in nature... that fully charged green, those “Kodak Moment” oranges’ (according to Calabresi), just as the Kar-a-Sutra promised a different way of thinking about the auto in an era of utter conformity.

Warhol’s studio at the Factory ’looked like the headquaters of a multinational’

Ultimately, Bellini says he is glad he revisited these places. ‘I’m a traveller, always curious,’ he says. ‘Most of my important journeys have been travelling in a van, wild camping. That’s what I’m used to.’ Even so, the social utopias had clearly given way to disenchantment and all the idealism that rolled west to California had largely evaporated. At the same time, the consumerist dreams of giant fridges, bottomless drinks and endless closets have made their way inexorably eastwards, for better or for worse. Then and now, Bellini sorted and shaped a very personal vision of the USA, seeking out the connections and imagery that endures to this day.

(Originally featured in the October 2015 edition of Wallpaper* (W*199))

At the inauguration of the first arch of Arcosanti, architect Paolo Soleri’s experimental town in the Arizona desert

INFORMATION

USA 1972, published by Humboldt Books, available from WallpaperStore*, €24

Photography: Mario Bellini

Jonathan Bell has written for Wallpaper* magazine since 1999, covering everything from architecture and transport design to books, tech and graphic design. He is now the magazine’s Transport and Technology Editor. Jonathan has written and edited 15 books, including Concept Car Design, 21st Century House, and The New Modern House. He is also the host of Wallpaper’s first podcast.

-

Ama Bar, in Vancouver, is sexy and a little disorienting

Ama Bar, in Vancouver, is sexy and a little disorientingAma Bar features ‘Blade Runner 2049’-inspired interiors by &Daughters

By Sofia de la Cruz Published

-

Kembra Pfahler revisits ‘The Manual of Action’ for CIRCA

Kembra Pfahler revisits ‘The Manual of Action’ for CIRCAArtist Kembra Pfahler will lead a series of classes in person and online, with a short film streamed from Piccadilly Circus in London, as well as in Berlin, Milan and Seoul, over three months until 30 June 2024

By Zoe Whitfield Published

-

Monospinal is a Japanese gaming company’s HQ inspired by its product’s world

Monospinal is a Japanese gaming company’s HQ inspired by its product’s worldA Japanese design studio fulfils its quest to take Monospinal, the Tokyo HQ of a video game developer, to the next level

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

‘Package Holiday 1968-1985’: a very British love affair in pictures

‘Package Holiday 1968-1985’: a very British love affair in pictures‘Package Holiday’ recalls tans, table tennis and Technicolor in Trevor Clark’s wistful snaps of sun-seeking Brits

By Caragh McKay Published

-

‘Art Exposed’: Julian Spalding on everything that’s wrong with the art world

‘Art Exposed’: Julian Spalding on everything that’s wrong with the art worldIn ‘Art Exposed’, Julian Spalding draws on his 40 years in the art world – as a museum director, curator, and critic – for his series of essays

By Alfred Tong Published

-

Marisol Mendez's ‘Madre’ unpicks the woven threads of Bolivian womanhood

Marisol Mendez's ‘Madre’ unpicks the woven threads of Bolivian womanhoodFrom ancestry to protest, how Marisol Mendez’s 'Madre' is rewriting the narrative of Bolivian womanhood

By Sofia de la Cruz Published

-

Photo book explores the messy, magical mundanity of new motherhood

Photo book explores the messy, magical mundanity of new motherhood‘Sorry I Gave Birth I Disappeared But Now I’m Back’ by photographer Andi Galdi Vinko explores new motherhood in all its messy, beautiful reality

By Hannah Silver Published

-

Best contemporary art books: a guide for 2023

Best contemporary art books: a guide for 2023From maverick memoirs to topical tomes, turn over a new leaf with the Wallpaper* arts desk’s pick of new releases and all-time favourite art books

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith Published

-

The best photography books for your coffee table

The best photography books for your coffee tableFlick through, mull over and deep-dive into the best photography books on the market, from our shelves to you

By Sophie Gladstone Published

-

Behind the scenes of Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining: new book charts the making of a horror icon

Behind the scenes of Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining: new book charts the making of a horror iconPublished in February 2023 by Taschen, a new collector's book will go behind the scenes of Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, charting the unseen making of a film that defined the horror genre

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith Published

-

Brad Walls’ aerial view transforms pools into artwork

Brad Walls’ aerial view transforms pools into artworkAerial photographer Brad Walls provides a crisp conclusion to the summer months with new book Pools From Above – you’ll want to dive right in

By Martha Elliott Last updated