Alive and kicking: 'Conceptual Art in Britain 1964–1979' at Tate Britain

Conceptual art is still alive and well, and an important part of contemporary art. But it really is no longer acceptable to use the terms 'conceptual' and 'contemporary' interchangeably, as a new show at Tate Britain demonstrates.

Though featuring some of the earliest examples of British conceptual art, the show’s dates, 1964–1979, do not span a meaningful period in art history at all. Rather they cover a specific era in British social and political history: the pre-Thatcher Labour government of 1964–1979. The Tate’s incoming director Alex Farquharson calls the show 'the ground zero' of British conceptual art. It helpfully pinpoints where British conceptualism was born (art schools and a handful of London galleries), what artists were reacting against (broadly speaking, modernism), the ideology behind conceptualism and how it sowed the seeds for something so much bigger.

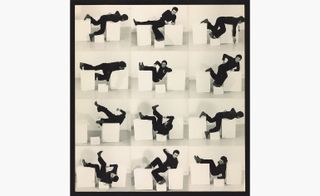

It’s not just the yellowing type-written archive material and David Tremlett’s sound map of Britain, a sculpture featuring 81 cassette tapes, that makes the art here feel dated. Many of the ideas are just so last century. Take Bruce McLean’s Pose Work for Plinths, in which the handsome young artist is seen draping himself ridiculously like a Charlie Chaplin Henry Moore over sculpture plinths. It’s 'an ironic reference to Caro’s rejection of the plinth', the blurb informs us. Remember that word, ironic? Remember a time when it was acceptable for museums to write mind-bending artwork blurbs like, 'Identifying art with disavowal creates an artwork that cancels itself'? This show is full of nostalgia for those days.

It was the era when artists wanted us to 'read' art, rather than look at it. And for that reason the show is drab, colourless, looks more like an archive than a gallery; there are 270 archival objects to 70 artworks. But it’s fun nonetheless. Think of the thrills artists had executing work like Hamish Fulton’s Hitchhiking Times from London to Andorra and from Andorra to London, 1967, and Michael Craig Martin’s glass of water entitled An Oak Tree, from 1973.

It’s a must-see; wear black clothes and an ironic smile, and take it all half-seriously.

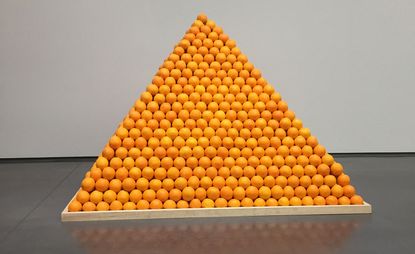

The Tate’s incoming director Alex Farquharson calls the show 'the ground zero' of British conceptual art. Pictured: ringn ‘66, by Barry Flanagan, 1966.

Pose Work for Plinths 3, by Bruce McLean, 1971.

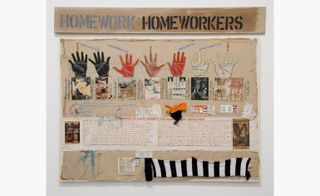

Homeworkers, by Margaret F Harrison, 1977.

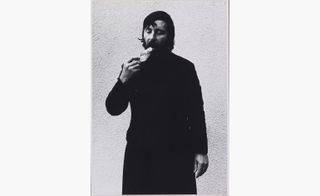

Self-Burial (Television Interference Project), by Keith Arnatt, 1969.

Art as an Act of Retraction, by Keith Arnatt, 1971.

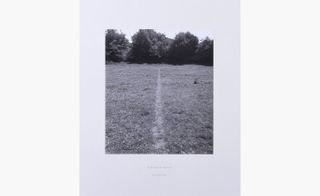

A Line Made by Walking, by Richard Long, 1967.

Sixty Seconds of Light (detail), by John Hilliard, 1970.

INFORMATION

’Conceptual Art in Britain 1964–1979’ is on view until 29 August. For more information, visit Tate Britain’s website

ADDRESS

Tate Britain

Millbank

London, SW1P 4RG

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox

-

Dial into the Boring Phone and more smartphone alternatives

Dial into the Boring Phone and more smartphone alternativesFrom the deliberately dull new Boring Phone to Honor’s latest hook-up with Porsche, a host of new devices that do the phone thing slightly differently

By Jonathan Bell Published

-

Berlinde De Bruyckere’s angels without faces touch down in Venice church

Berlinde De Bruyckere’s angels without faces touch down in Venice churchBelgian artist Berlinde De Bruyckere’s recent archangel sculptures occupy the 16th-century white marble Abbazia di San Giorgio Maggiore for the Venice Biennale 2024

By Osman Can Yerebakan Published

-

Discover Acqua di Parma’s new Mandarino di Sicilia fragrance at Milan Design Week 2024

Discover Acqua di Parma’s new Mandarino di Sicilia fragrance at Milan Design Week 2024Acqua di Parma and Fornice Objects bring the splendour of Sicilian mandarin fields to Milan to celebrate new fragrance Mandarino di Sicilia

By Simon Mills Published

-

Yinka Shonibare considers the tangled relationship between Africa and Europe at Serpentine South

Yinka Shonibare considers the tangled relationship between Africa and Europe at Serpentine SouthYinka Shonibare‘s ‘Suspended States’ at Serpentine South, London, considers history, refuge and humanitarian support (until 1 September 2024)

By Tianna Williams Published

-

Gavin Turk subverts still-life painting and says: ‘We are what we throw away’

Gavin Turk subverts still-life painting and says: ‘We are what we throw away’Gavin Turk considers wasteful consumer culture in ‘The Conspiracy of Blindness’ at Ben Brown Fine Arts, London

By Rowland Bagnall Published

-

Dorothy Hepworth and Patricia Preece: Bloomsbury’s untold story

Dorothy Hepworth and Patricia Preece: Bloomsbury’s untold story‘Dorothy Hepworth and Patricia Preece: An Untold Story’ is a new exhibition at Charleston in Lewes, UK, that charts the duo's creative legacy

By Katie Tobin Published

-

Don’t miss: Thea Djordjadze’s site-specific sculptures in London

Don’t miss: Thea Djordjadze’s site-specific sculptures in LondonThea Djordjadze’s ‘framing yours making mine’ at Sprüth Magers, London, is an exercise in restraint

By Hannah Silver Published

-

‘Accordion Fields’ at Lisson Gallery unites painters inspired by London

‘Accordion Fields’ at Lisson Gallery unites painters inspired by London‘Accordian Fields’ at Lisson Gallery is a group show looking at painting linked to London

By Amah-Rose Abrams Published

-

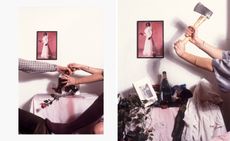

Fetishism, violence and desire: Alexis Hunter in London

Fetishism, violence and desire: Alexis Hunter in London‘Alexis Hunter: 10 Seconds’ at London's Richard Saltoun Gallery focuses on the artist’s work from the 1970s, disrupting sexual stereotypes

By Hannah Silver Published

-

Wayne McGregor’s new work merges genetic code, AI and choreography

Wayne McGregor’s new work merges genetic code, AI and choreographyCompany Wayne McGregor has collaborated with Google Arts & Culture Lab on a series of works, ‘Autobiography (v95 and v96)’, at Sadler’s Wells (12 – 13 March 2024)

By Rachael Moloney Published

-

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley confronts gaming, VR and rebirth at Studio Voltaire

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley confronts gaming, VR and rebirth at Studio VoltaireDanielle Brathwaite-Shirley has opened her first institutional solo exhibition, ‘THE REBIRTHING ROOM’, at Studio Voltaire, London

By Hannah Silver Published