Mid-career manifesto: Sir David Adjaye pauses to reflect on his design philosophy

Sir David Adjaye’s new book Constructed Narratives, edited by Peter Allison and published by Lars Müller, is an informal manifesto of the architect’s design principles and architectural approach, reflecting on almost 25 years of work.

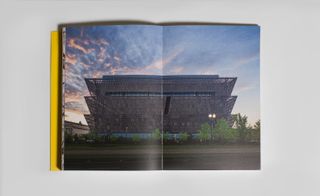

Following the completion of Washington's Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture (SNMAAHC) in September 2016, and then receiving a knighthood this year, the book marks a poignant moment in time for the mid-career architect.

‘Making this book helped me to organise my approach and philosophy in a much more formal way than I had ever done previously,’ says Adjaye.

‘In the past, it had been a guiding ethos for my practice, but drawing out the themes for this book has made me even more determined to remain resolute in my dedication to responsiveness, to architecture that demonstrates empathy with its users and its surroundings, and to innovating typologies that can guide our cities into the future,’ he says.

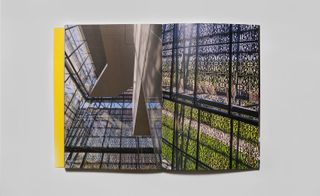

Examples of the filigree-style facade of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC

Through case studies and essays, the book connects the dots between the architectural shapes and styles that Adjaye has constructed across the world, from New York to London and Beirut, formulating a philosophy in the shape of a constellation, covering urban design, geography and various architectural typologies.

Sparking this reflective approach to his career was the completion of his ‘largest and most complex project’, the SNMAAHC.

‘The museum was the culmination of eight years of work, but in many ways it felt like the culmination of the past 15 years, since I set up my office. I felt it provided a natural pivot point in my practice... like the proper close to a previous chapter, and the exciting launch pad for the next,’ says Adjaye.

Occupying the last remaining space on Washington’s National Mall, the SNMAAHC was a milestone for Adjaye and his retrospective narrative reads as if it was destined for him. Maybe it was.

‘My ideal public building has a square plan and is visible from all sides,’ he states in the book, in an essay on public architecture. Square buildings, he continues, are not as common as you would think – illustrating his reflection with examples drawn from architectural history, from the Great Mosque of Cordoba to Le Corbusier’s Palace of Assembly in Chandigarh, Louis Kahn’s Jewish Community Centre and the cultural examples of mandalas and Persian gardens.

Eloquently communicated, Adjaye’s ideas have a sense of determination that doesn’t shy away from idealism and rhetoric, yet he is never brusque or demanding, only measured and hopeful. The SNMAAHC culminates his architectural philosophy in one magnificent statement.

The dark earth-coloured, lightweight facade of bronze cladding achieves balance between form and density. It is powerful yet approachable. Adjaye traces his use of dark exteriority to his first building, Elektra House (2000), built with dark brown resin-coated plywood. ‘This was when I started thinking about building forms as voids,’ he writes in the essay ‘Toward Black’.

He used different types of darkness in the Bernie Grant Arts Centre (2002–2007), building with black clad ceramic tiles, dark brown corrugated sheet and brown cement fibre board to distinguish different parts of the project.

At Rivington Place (2007) he contrasted black precast concrete cladding with the ochres, oranges and greys of Georgian brickwork. ‘When you are in the street, it is an imposing building that is in retreat. I attribute this to the light absorbing qualities of the dark facades; it is both a strong form and a relaxed form,’ he writes – which could also be said of the SNMAAHC.

Cemented in the foundations of this building, Adjaye’s design philosophy is configured in Constructed Narratives by reflecting back over the past. Yet, the satisfaction of finishing the last page of a great book, closing the cover and placing it down, is always followed by a new adventure.

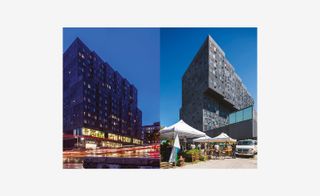

Views of Adjaye’s Sugar Hill building in New York. Built from 2011–2014, it features affordable housing for families, an early childhood centre and the Sugar Hill Children’s Museum of Art and Storytelling

The Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC, constructed 2009–2016

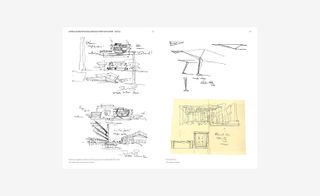

Details of preliminary sketches of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC

Detail of the facade of the waterfront Aïshti Foundation in Beirut, constructed 2012–2015

INFORMATION

Constructed Narratives, by David Adjaye, edited by Peter Allison, €45. Published by Lars Müller. For more information, visit the publisher's website

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox

Harriet Thorpe is a writer, journalist and editor covering architecture, design and culture, with particular interest in sustainability, 20th-century architecture and community. After studying History of Art at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) and Journalism at City University in London, she developed her interest in architecture working at Wallpaper* magazine and today contributes to Wallpaper*, The World of Interiors and Icon magazine, amongst other titles. She is author of The Sustainable City (2022, Hoxton Mini Press), a book about sustainable architecture in London, and the Modern Cambridge Map (2023, Blue Crow Media), a map of 20th-century architecture in Cambridge, the city where she grew up.

-

Ama Bar, in Vancouver, is sexy and a little disorienting

Ama Bar, in Vancouver, is sexy and a little disorientingAma Bar features ‘Blade Runner 2049’-inspired interiors by &Daughters

By Sofia de la Cruz Published

-

Kembra Pfahler revisits ‘The Manual of Action’ for CIRCA

Kembra Pfahler revisits ‘The Manual of Action’ for CIRCAArtist Kembra Pfahler will lead a series of classes in person and online, with a short film streamed from Piccadilly Circus in London, as well as in Berlin, Milan and Seoul, over three months until 30 June 2024

By Zoe Whitfield Published

-

Monospinal is a Japanese gaming company’s HQ inspired by its product’s world

Monospinal is a Japanese gaming company’s HQ inspired by its product’s worldA Japanese design studio fulfils its quest to take Monospinal, the Tokyo HQ of a video game developer, to the next level

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

Marcio Kogan’s Studio MK27 celebrated in this new monograph from Rizzoli

Marcio Kogan’s Studio MK27 celebrated in this new monograph from Rizzoli‘The Architecture of Studio MK27. Lights, camera, action’ is a richly illustrated journey through the evolution of this famed Brazilian architecture studio

By Jonathan Bell Published

-

‘Interior sculptor’ Christophe Gevers’ oeuvre is celebrated in new book

‘Interior sculptor’ Christophe Gevers’ oeuvre is celebrated in new book‘Christophe Gevers’ is a sleek monograph dedicated to the Belgian's life work as an interior architect, designer, sculptor and inventor, with unseen photography by Jean-Pierre Gabriel

By Tianna Williams Published

-

Flick through ‘Brutal Wales’, a book celebrating concrete architecture

Flick through ‘Brutal Wales’, a book celebrating concrete architecture‘Brutal Wales’ book zooms into a selection of concrete Welsh architecture treasures through the lens of photographer Simon Phipps

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

Architecture books to inspire shelf love

Architecture books to inspire shelf loveHere at Wallpaper*, we’ve got architecture books piling up; among them, these are the photographic tomes, architects’ monographs and limited editions that we couldn’t resist

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

130 William by Adjaye Associates’ holistic vision is unveiled in New York

130 William by Adjaye Associates’ holistic vision is unveiled in New YorkWe unveil the holistic design of Adjaye Associates’ 130 William, the residential scheme that has just completed in New York

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

Pioneering modernist Henry Kulka's life and career tracked in limited-edition monograph

Pioneering modernist Henry Kulka's life and career tracked in limited-edition monographCzech-New Zealand architect Henry Kulka, a man who spread modernist ideals half way around the world, is celebrated in Giles Reid and Mary Gaudin’s richly illustrated monograph

By Jonathan Bell Published

-

Nordic architecture explored in Share, a book about contemporary building

Nordic architecture explored in Share, a book about contemporary buildingDiscussions about Nordic architecture and contemporary practice meet in a new book by Artifice, Share: Conversations about Contemporary Architecture – The Nordic Countries

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

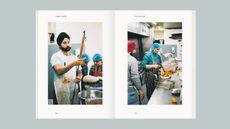

London Feeds Itself: we are hungry for Open City's book on food and architecture

London Feeds Itself: we are hungry for Open City's book on food and architectureLondon Feeds Itself, a new book by Open City, is a scrumptious offering that connects food culture and architecture

By Nick Compton Last updated